LONDON • The Iranian government has succeeded in stamping out a wave of protests which have struck the country since the start of the new year.

Nevertheless, although what has happened in Iran over the past week may now look of very little practical importance, this could be the start of a very significant shift in the Middle East. For the latest Iranian events are stark evidence of just how brittle the country is, and how abruptly its fortunes may change. And the demonstrators also provided a reminder that those in the West who advocate a more aggressive posture against the current Iranian government may not be wrong.

Despite the often excited reporting in the Western media which sought to convey the image of a revolution in the making, the latest troubles in Iran never looked likely to develop into a serious challenge for the regime, and were never remotely like the 2009 so-called Green Movement of protests.

Back in 2009, urban and largely Teheran-based middle class people, angered at alleged vote rigging in a presidential election, poured into the streets in their hundreds of thousands. They also had a platform, rallying around the policies of Mr Mir Hossein Mousavi, a reformist idol and a former Iranian prime minister.

But the recent protests in Iran appear to reflect the anger of the country's working-class masses, of Iranians who grapple with high inflation, unemployment and economic corruption, people who have no leadership, and are therefore no immediate threat to the institutions of the current Iranian state. As a result, protesters adopted chants cursing just about every actor and political affiliation in Iran. There were frequent chants of "death to Rouhani" - referring to Iran's reform-minded centrist President Hassan Rouhani - as well as calls for the demise of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the country's supreme leader, as well as for the restoration of the old Shah monarchy, and for more jobs and food subsidies.

So although all Western intelligence agencies watched the Iranian events over the past week with great care, no Western government - not even that of Mr Donald Trump which was most vociferous in its public statements of support for the demonstrators - believed for one second that the Teheran regime was genuinely under threat.

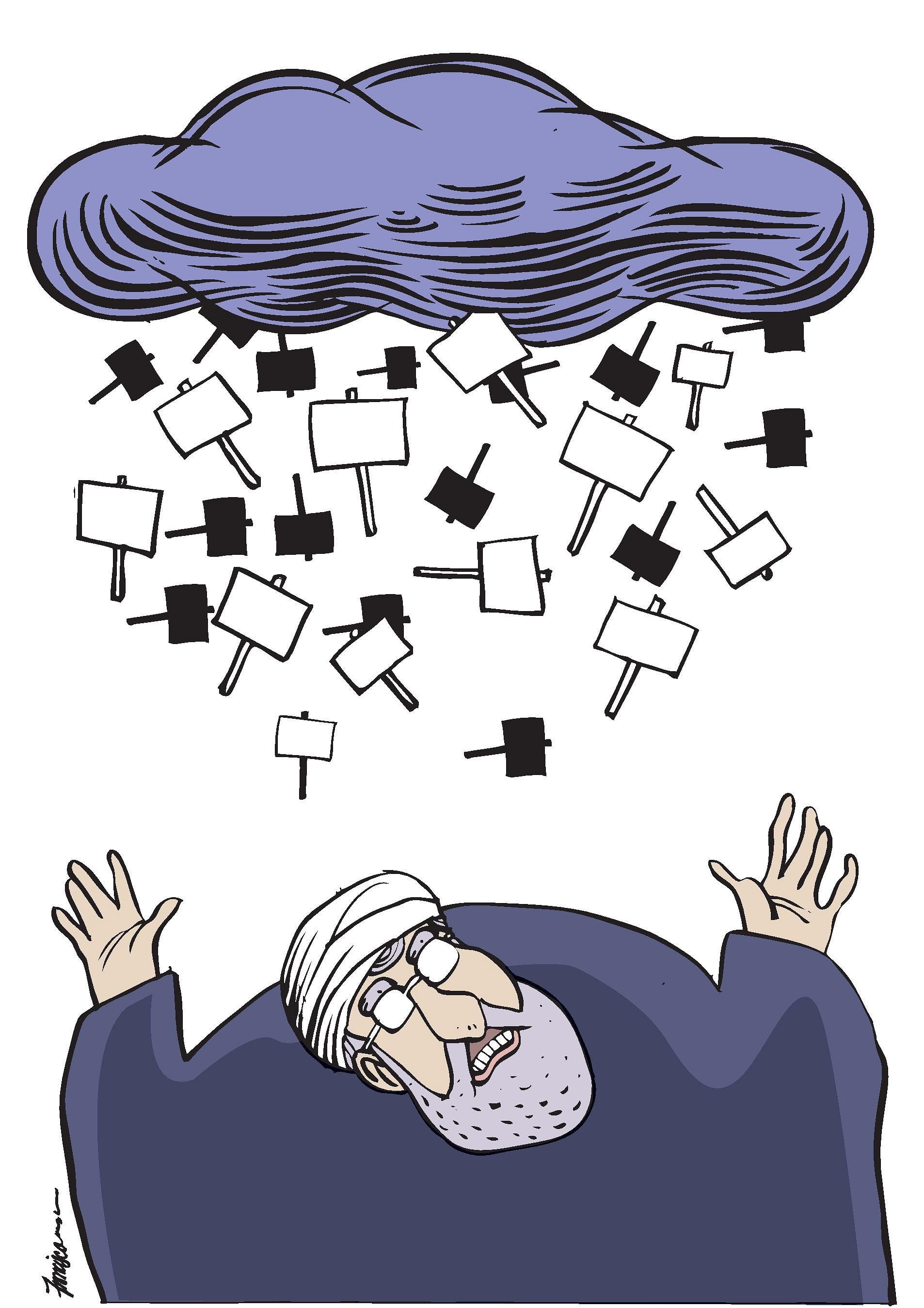

Still, what has happened in Iran is more than just a storm in a teacup.

LEGITIMACY HURT

First, the demonstrations hurt the legitimacy of the regime. Iran always prided itself on being an exception in the Middle East, one country which operates "mature" politics in which various institutions balance each other and people elect their representatives. But it is now exposed as a country in which the only deciding factor is force. The demonstrations also increased the pressure on the authorities to produce economic results, precisely what Teheran's rulers find most difficult.

And they also indicated that, despite all the official propaganda, even uneducated and rural-based Iranians are fully aware of the high levels of corruption in their country, and of the fact that the Revolutionary Guards, the regime's all-powerful force, are at the epicentre of this corruption.

It was noticeable that many of the demonstrators chanted slogans against Iranian intervention in Lebanon and Syria, demanding that the money spent on these adventures should be used to alleviate poverty back home.

And when the violence erupted, this was mainly directed at businesses operated by the Revolutionary Guards.

NATIONALISM REASSERTED

But perhaps the most important outcome of the demonstrations is the re-emergence or reassertion of Iranian nationalism. For the first time, both demonstrators and people close to President Rouhani have started referring to the Iranian "nation" and Iran's national needs, concepts which were banned under Ayatollah Khomeini, the leader of Iran's clerical revolution, who preferred to refer to a global Islamic ummah or community. The mullahs who run Iran were put on notice that all their dogmatic proselytising has not worked and that, at least for the opponents of the regime, the country's religious government is seen as detrimental to Iran's national interests.

THE AFTERMATH

Does all this ultimately matter? It does, and a great deal. To start with, it's worth recalling that in every single one of the four decades since the Iranian revolution, the clerics faced a major popular domestic dissent which threatened to overwhelm them; that hardly indicates a regime designed to last.

Furthermore, Iran's population growth is not predicted to stabilise before the middle of this century, and we now know that young people in both cities and countryside are dissatisfied; at least in this context, a link between the demonstrations now and those held back in 2009 does make sense.

And in any case, people who appear rudderless and unfocused frequently do make history. Anyone who predicted in January 1989 that the Soviet empire in Europe would be over soon and that a clutch of workers and a few intellectuals could bring down governments which operated hundreds of thousands of secret service agents would have been told to go and have his head examined. But by the end of that year, that's precisely what happened.

The same happened in Iran itself a decade earlier, when students of no ideology or little organisation poured into the streets, only to be initially dismissed by everyone as irrelevant; a few months later, the all-powerful Shah was gone.

But even if there are no immediate ripple effects inside Iran, the country's international position looks likely to deteriorate drastically and fast. For European governments, the events in Iran come at a particularly awkward time, just as the Europeans lined up to express their strong support for the continuation of the Iran nuclear deal, which US President Donald Trump is keen to ditch.

The deal remains in place, and its importance is as strong as ever. Still, as the debate moves away from nuclear matters to the domestic situation inside Iran, it is difficult for the Europeans to claim that the nuclear deal accomplished what it was touted to do. Instead of transforming Iran into a more cooperative country, the last few years have seen soaring Iranian involvement in the affairs of its Middle Eastern neighbours and a clear Iranian gambit to become the region's pre-eminent power.

The easing of economic sanctions has only benefited the pillars of the regime, rather than "empowering a new middle class" inside Iran, as former US president Barack Obama used to claim.

And the cash which Iran was allowed to repatriate from frozen bank accounts in the West was indeed used to fund the creation of Shi'ite-based paramilitary forces, used by Iran to destabilise a number of Middle Eastern countries. It may be monumentally unfashionable to say so now, but President Trump may have been more right than wrong when he labelled the West's entire policy towards Iran as a failure.

Be that as it may, while Mr Trump has been relatively restrained in his immediate reactions ("the world is watching what Iran is doing" was his strongest Twitter response and the convening of a UN Security Council meeting was just gesture politics), there is no question that the events have only strengthened the position of US officials determined to squeeze Iran and corner its regime, in order to produce a regime change.

The entire US administration is in any case dominated by "Iran hawks", from General H.R. McMaster, the National Security Adviser, to Mr Derek Harvey, the senior director for the Middle East in the National Security Council, and right up to Mr Mike Pompeo, the CIA director.

The recent appointment of Mr Michael D'Andrea, the senior CIA official who oversaw the hunt for Osama bin Laden, as head of the agency's Iran operations is an indication of where the US administration wishes to go from now on: towards activities intended to destabilise the Iranian regime.

The sudden emergence of reports in the Israeli media that Washington has given Israel's intelligence services the green light to assassinate General Qassem Soleimani, the head of the Quds Force, the overseas arm of Iran's Revolutionary Guards, is a further indication that destabilisation efforts are now the order to the day; Gen Soleimani's assassination was reputedly vetoed by the Americans in the last days of the Obama administration. And economic sanctions against Iran will be tightened.

In short, while the demonstrations in Iran were never likely to morph into regime change, they will inspire regime change temptations in Washington, weaken the Europeans' interest in forging new relations with Iran, and make Iran the top priority of the US administration in the Middle East.

So, the clerics in Teheran may be in charge for now, but they are likely to experience a very testing year.