LONDON • Dr Willis Ware had the knack of being in the right place at the right time. He was a pioneer scientist, one of the main contributors to the development of digital computing from the 1940s onwards. And, as a member of the US National Security Agency's Scientific Advisory Board during the 1960s, he became one of the first people to warn that once governments start putting their information on computer networks that can be accessed from multiple locations, countries won't be able to keep secrets any more.

The distinguished scientist who died in 2013 would, no doubt, have felt vindicated by the Singapore Government's recent decision to enhance safety by delinking computers used by civil servants from direct access to the Internet.

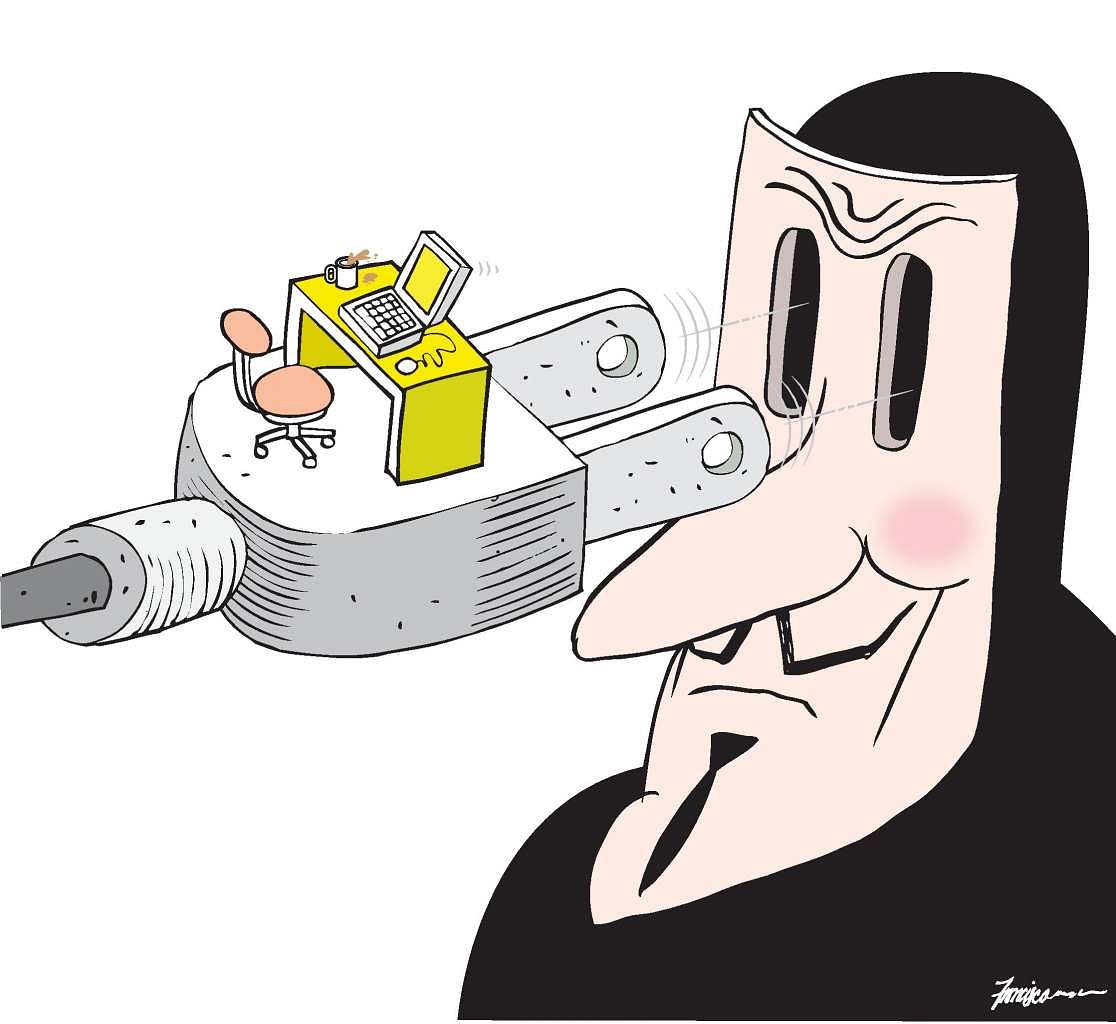

The idea that we should now go against the "Internet of Things", that instead of seeking to control everything with a swipe on our handheld device we should instead create walls between computer systems, may appear to harken back to the activities of the Luddites, the early 19th century workers who went around England destroying factory machinery in the hope of protecting their jobs from the industrial revolution: it appears as an act which is not only counter-productive, but also pointless.

Yet by taking the disconnection route, Singapore's Government may actually herald a global trend. For it is by now abundantly clear that many of the current strategies designed to ensure computer security and vital data integrity are not working, that the entire subject requires a fundamental reappraisal, and that going back to basics, to a period when not all computer systems were interlinked, is a useful way to launch this rethink.

Damages from computer security breaches cost the global economy an estimated US$400 billion (S$544 billion) annually, according to calculations by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a US-based think-tank. Yet this pales into insignificance in comparison with developments in cyber confrontations between nations.

The term "cyber warfare" was coined during the 1990s, but military strategists didn't initially treat the concept seriously, with Mr Howard Schmidt, US President Barrack Obama's first cyber security "czar", once dismissing the entire concept as a "terrible metaphor".

But the critics were simply wrong. For although cyber capabilities are constantly changing and a country is only as good as its latest technological advances, certain nations have built such a massive advantage in this field as to be able to contemplate the use of cyber warfare in any conflict, with a reasonable degree of certainty that this would work to their advantage.

THE NEW CYBERWAR THREATS

China is often identified as the originator of many cyber intrusions, allegedly tolerated or even encouraged by its government. The US and Britain were also revealed as key operators in this field. But as security experts know, the real global leader is Russia; its stealthy operators are regarded as the true "gold standard" in cyber warfare.

Meanwhile, government vulnerabilities increase all the time, since much of every nation's critical national infrastructure - banks, all utility installations, roads and aircraft traffic control systems to name but a few - ultimately depend on interlinked computer systems. It's not for nothing that Mr Leon Panetta, who served as President Obama's defence secretary and chief of the Central Intelligence Agency, once prophesied that America's "next Pearl Harbour" military surprise "could very well be a cyber attack".

As the ultimate custodians of their nations' biggest collections of data in almost every field, governments are also targeted by malicious organisations and criminal individuals. And although protecting the secrecy of communications and data has been a problem for centuries, it is particularly so today, for in the era when information was stored on paper, a security leak would have involved the loss of a few pages of sensitive data. But today, the smallest of security mishaps results in the exposure of, literally, millions of pieces of information.

There are plenty of such mega-disaster examples, from every continent.

Last year, the US Office of Personnel Management, the agency that manages America's federal civil service, admitted that the files of 21.5 million people were stolen from its servers. Earlier this year, every registered voter in the Philippines became vulnerable to fraud after the entire database of the Philippines' Commission on Elections was compromised.

That won't come as a shock to the people of Turkey, where servers belonging to the Interior Ministry leaked the personal records of 49.5 million citizens, or to people in Greece, where highly sensitive personal information on nine million people - 86 per cent of the local population - was stolen.

And then, there are the major security breaches perpetrated by hostile governments seeking information, such as last year's theft of e-mails from the servers of the US State Department which was so clever that America's National Security Agency needed months before it succeeded in evicting the intruders from its servers.

Or are the intruders still there? How does one know for sure that the US State Department's servers are clear of previous intrusions, or uninfected by fresh ones?

One of the fundamental problems with enforcing cyber security in any government machinery is that the people who have the technical knowledge and responsibility for policing the integrity of the structures are often not the ones to decide how these systems are ultimately used, while officials higher up who do make decisions about how their systems are deployed seldom have the detailed technical knowledge.

'RETRO' SOLUTIONS

The result is an almost perpetual ignorance loop, as ministers and politicians know that their systems are inherently insecure, but are resigned to continue using them since they are unable to quantify the risks involved. And the risks may be huge: as American journalist Fred Kaplan points out in his recently published book Dark Territory: The Secret History Of Cyber War, whenever the US military stages war games in which experts are invited to hack into its systems, "they always get in".

By deciding to delink some computers from the Internet, the Singapore Government has effectively signalled that, faced with unquantifiable risks, one prudent course is simply to roll back technology. And in that respect, Singapore may be a trend-setter, for other governments are also mulling over similar approaches.

A handful of highly sensitive computer systems operated by the British government are already permanently disconnected from the Internet, or connected to an internal network whose physical integrity is entirely contained within one office.

The Russian intelligence services also revealed a few years ago that some of their most classified materials will continue to be generated by old-fashioned typewriters.

More significantly, members of the US Senate's Intelligence Committee currently looking at ways to protect America's critical national infrastructure are examining a new Bill which will compel the US energy grid to replace some key computer- connected structures with "analogue and human-operated systems", as Senator Martin Heinrich, one of the new legislation's drafters, puts it. "A 'retro' approach has shown promise as a safeguard against cyber attacks," he told fellow US lawmakers.

None of these "retro" initiatives offers impregnable security, for old technology has its own vulnerabilities. Keyboards of typewriters can be eavesdropped, allowing the text of what is being typed to be recorded, as Soviet intelligence proved during the 1970s, when it successfully planted such eavesdropping devices in US diplomatic offices. And the information stored on computers not connected to the Internet can also be hacked or pilfered wirelessly.

So, the real significance of Singapore's decision is that it forces decision-makers to have another look at the balance between the efficiency of electronic systems and the dangers they entail. Yet the decision to downgrade on the use of technology is not the solution but merely a solution, and a temporary one at that, pending a better understanding of these risks and opportunities.

For, as computer pioneer Willis Ware also accurately pointed out decades ago, ultimately "the only completely secure computer is a computer that no one can use".