The computer screen lights up with blotches of green and red, formless shapes moving here and there.

I am watching these dancing images, ignorant and clueless, next to a man who knows exactly what is taking place.

I see meaningless colours; he sees body cells responding to an injury.

Can the gulf between two persons be so large that we see the same thing, but he everything and I nothing?

That's how I feel, here in one of the many laboratories I am visiting at Biopolis.

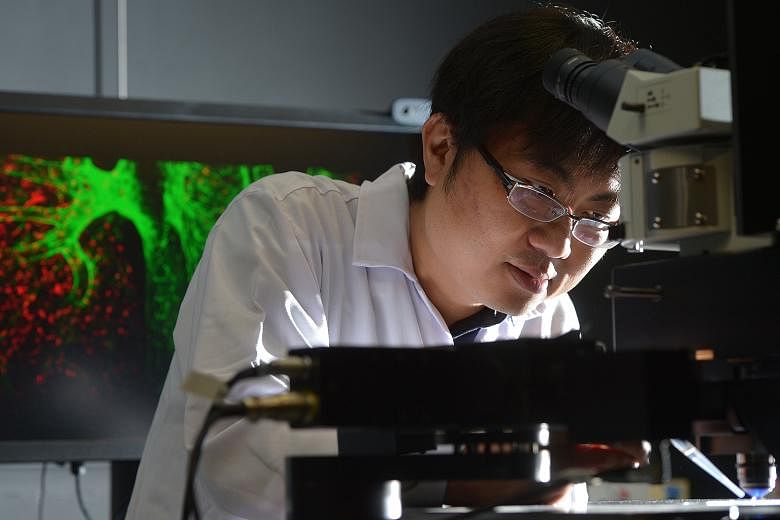

Dr Ng Lai Guan, principal investigator at the Singapore Immunology Network (A*Star), in his laboratory, with a coloured image of a bone marrow niche behind him. He uses the latest scientific imaging technologies to study how immune cells behave in their native tissues and organs. ST PHOTO: JAMIE KOH

Dr Ng Lai Guan, principal investigator at the Singapore Immunology Network (A*Star), in his laboratory, with a coloured image of a bone marrow niche behind him. He uses the latest scientific imaging technologies to study how immune cells behave in their native tissues and organs. ST PHOTO: JAMIE KOH This is the heart of Singapore's multibillion-dollar biotechnology investment where hundreds of talented researchers equipped with the latest cutting edge instruments practise weird and complicated science.

I am trying to understand what is taking place, who are the people involved and how well the projects are doing.

At the Singapore Immunology Network (SIgN) which is part of A*Star, the national body spearheading scientific research, Dr Ng Lai Guan is trying his darndest to explain the what.

The video I was watching was captured by a microscope aimed at the ear of a mouse that had a part of it deliberately damaged by laser to study how the inside of the body reacts to an injury.

The magnification is so powerful it is possible to observe cells and proteins at work. This is a world of the basic building blocks of life .

But you can't just place any old mouse under any old looking glass. This laboratory mouse has been genetically modified so that the relevant cells will show up in different colours when the action takes place. Otherwise you wouldn't be able to tell what was taking place and interpret the subsequent action.

This is valuable science because if you can observe how actual cells behave in the body of a living animal and watch it in real time, you might begin to unravel part of the mysterious way life works, and discover new ways of fighting disease and injury.

Before this, scientists had to make do by removing the damaged or diseased part and studying the sliced and very dead specimen in a laboratory.

It's the difference between a black and white photo and a technicolour live video recording.

It is also very complicated science because real-time imaging like this requires a combination of skills in microbiology, physiology and biophysics.

You need to clone the mouse, do surgery on it, handle the expensive microscopy (this particular one is called an intravital multiphoton microscope) and be able to analyse all that data from those dancing images.

It is why it is so expensive to do.

Singapore is committed to spending $19 billion in its latest five-year R&D budget, from 2016 to 2020, with a significant part on biomedical science which has been identified as an important sector of its future economy.

Some of the areas scientists here are hoping to make a breakthrough in include research on cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, infectious diseases as well as neurological and other sense disorders.

SIgN specialises in immunology, which is a study of the immune system in living things. Its current work includes research on dengue and chikungunya.

I have also come to find out more about the people who spend their professional life studying killer diseases and peering endlessly at computer screens.

Dr Ng, 39, is one of the leading scientists on live imaging of this sort, but you wouldn't have known it, looking at his boyish face and crumpled T-shirt.

He looked like he might have just hopped off the bus from Parit Buntar in the northern Malaysian state of Kedah where he hails from.

Like many talented Malaysians who now make Singapore their home, his was a small town to big city story: Parit Buntar to the University of New South Wales in Australia for his undergraduate degree in biomedical science; PhD from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney; joined the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore, in 2004; off to Wistar Institute at the University of Pennsylvania in the US which specialises in cancer and vaccine research; and recruited by A*Star in 2009.

He tells me two stories that have influenced his research career.

While studying in Australia, he received word that his grandmother was gravely ill. He returned home and spent two months looking after her before she died. The experience made him decide to switch to medical science and he hasn't looked back since.

He also tells me that the chair I am sitting on, across from his table in his office, was where the Nobel Prize winner Ralph Steinman sat when he visited Dr Ng six months before he died in 2011.

Dr Steinman won the Nobel Prize in medicine that year for his work on a type of cells that triggers the body's immune system - which he named dendritic cells.

Dr Ng had published a paper on these cells during his postgraduate studies but had not continued work on it, and he remembers what Professor Steinman told him that day: Don't give up on your study.

He hasn't.

The facilities and equipment here, he tells me, are world class, and the support he gets from A*Star is outstanding.

The biggest challenge though is not the science, but getting good Singaporean PhD students to join the research team.

He says that, intellectually, they are as good as the best in the world but they have to be committed and dedicated to a life of research.

Not hungry enough?

It's a problem even at the top of the scientific food chain.

I meet his boss, Professor Laurent Renia who came over from France in 2007 to start SIgN and who specialises in malaria research.

He says the scientific world is a fast-moving one and researchers here have to keep up with the best or risk being left behind.

He is proud of what SIgN has achieved and cites its success in developing a test kit to detect 26 pathogens that cause 13 tropical diseases.

But there is much more to be done.

Singapore's multibillion-dollar R&D bet isn't just about making a mark in the scientific world but part of a broader effort to transform itself.

It can no longer rely on being just a place where foreign companies set up their factories, but must build its own, invent new products, innovate new ways to serve its customers, and, yes, discover new cures for diseases.

Can Singapore make this leap and join the ranks of the advanced countries?

Part of the answer lies in places like SIgN where cutting edge work is being done.

Dr Ng hopes one day to make a breakthrough that might change the practice of medicine.

Singapore needs many more of these people, each working in his own area of expertise, to make a difference across the economy.

It is painstaking, demanding work with no guarantee of success.

That's what it takes to make it to First World ranking.

•This is part of an occasional series by the writer on science and technology in Singapore.