LONDON • He has yet to complete a week in office, but the security credentials of Mr Moon Jae In, South Korea's new president, have already been challenged as North Korea yesterday carried out another intermediate-range ballistic missile test.

President Moon reacted to the test in the only way he could - by condemning the missile launch and by ordering his military to be prepared for further provocations from the North.

But behind this seemingly decisive response lurks a familiar South Korean problem: a dysfunctional domestic political system and a reluctance to embrace truly radical foreign and security policy options, both of which lead to a tendency to go for the lowest common denominator by clinging to old approaches doomed to failure.

There is no question that Mr Moon has a strong mandate for change. With a 17-percentage- point lead over his nearest rival in the elections, his victory margin was the highest recorded in any South Korean presidential ballot.

The latest election also witnessed the highest turnout of voters in more than two decades. And although Mr Moon qualified to be president with only 41 per cent of the overall votes cast, well over half of South Koreans in their 20s and 30s backed him, a sure sign that they expect a very different future.

But the political system in which he is expected to work is one of the most dysfunctional among developed industrialised nations. No other country of comparable size to South Korea elects its top political executive for a single, non-renewable five-year term.

And no other country of such importance has a comparable system in which the president exercises such significant executive powers, but so does its Parliament, with the mechanisms for arbitration between legislature and executive remaining hotly and permanently contested.

Even if everything goes according to plan and Mr Moon's own liberal Minjoo party flourishes, the newly elected president will have to wait until the end of this decade before he can have his allies in control of Parliament and the true business of reform can begin.

But by 2020, not only Mr Moon's opponents but also his allies will be looking for the next presidential candidate; the current president is likely to be dismissed as a "lame duck".

In short, what South Korea really needs is root-and-branch constitutional reform, rather than gesture politics such as Mr Moon's refusal to move into the Blue House.

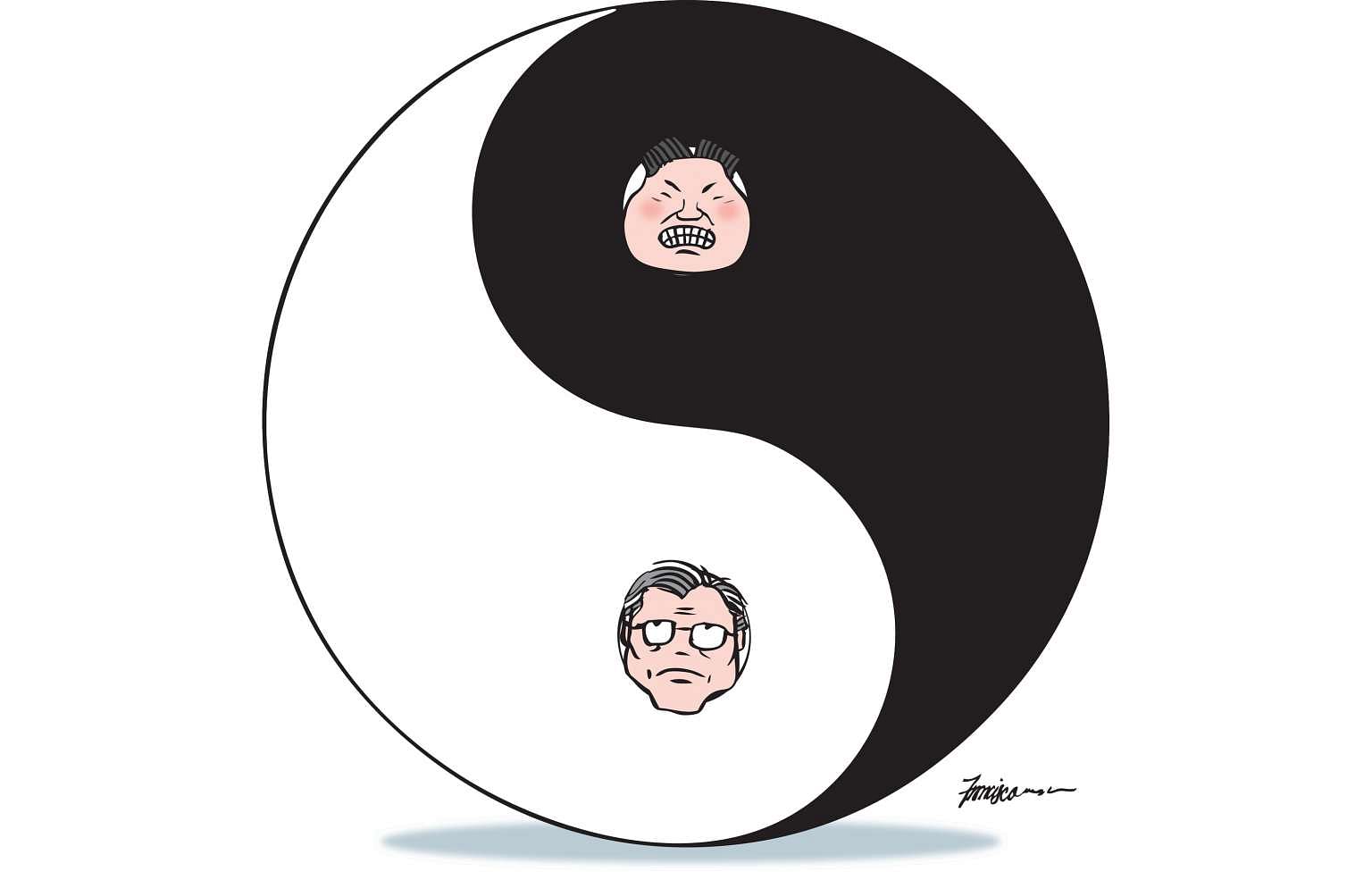

But as the response to yesterday's North Korean missile test indicates, the biggest problem may come from the fact that Mr Moon's foreign and security policies - key priorities in a divided nation constantly on the brink of war - seem to consist of nothing more than a repeat of the policies of his predecessors. These entailed attempts to talk to North Korea, get close to China, and pick up historical disputes with Japan. The snag is that all three policies resemble characters from a badly scripted theatrical farce: doomed to fail, largely irrelevant and not particularly amusing either.

WASTE OF 'SUNSHINE'

Rumours are rife that, notwithstanding current rebuffs from North Korea, Mr Moon may be about to embark on a "Sunshine 2.0" initiative, a renewed attempt to engage with Pyongyang by offering North Korean leader Kim Jong Un economic incentives in return for concessions on nuclear and other security questions.

The case for this seems compelling: Nothing else has worked.

And the policy has a good pedigree: The first "sunshine" attempt earned one South Korean president a Nobel Peace Prize and its continuation was the hallmark of Mr Roh Moo Hyun, the late South Korean leader whom President Moon served.

But it is inconceivable that the current leader will get anything meaningful out of such an approach. For all the bagfuls of free rice and friendly security reassurances that South Korea could offer would never equal the security which Pyongyang believes it will get once it has a credible nuclear-delivery capability.

A new Sunshine Policy will probably violate the newly imposed international economic sanctions on North Korea. It will also embroil President Moon in precisely the sort of corrupt payment and subsidy practices which destroyed the reputation of Mr Roh, his mentor. And the only way the Kaesong industrial complex, where North and South Koreans used to work together, can be restarted is by President Moon appealing for the assistance of the same South Korean chaebol family enterprises he has now pledged to cut down to size.

In essence, a revived Sunshine Policy is the easiest way to fritter away a political career in pursuit of a non-existent peace.

The attempt to draw closer to China in order to get Beijing to put pressure on North Korea is another of those policy tropes pursued by successive South Korean presidents; Park Geun Hye, President Moon's disgraced immediate predecessor, was a great disciple of this strategy.

But the policy invariably failed because what the Chinese can offer, which is to put some pressure on Pyongyang, is always disappointingly little for South Korea, while what Beijing demands in return - restrictions on South Korea's military cooperation with the United States and, perhaps, a reduced US military presence on the Korean peninsula - is simply too high a price for Seoul.

There are some very practical strategic reasons why China may wish to keep the Korean peninsula perpetually divided. And it is difficult to see what pressure President Moon can put on Beijing or what incentive he can dangle to trump what US President Donald Trump is already offering China on this score. For sure, the Chinese may agree to lift the trade sanctions they have "informally" imposed on South Korea in return for Mr Moon's agreement to halt the deployment of America's Terminal High Altitude Area Defence missile system on the peninsula. But that will embroil South Korea in a monumental confrontation with the US.

THE JAPAN CARD

And then, there is the other and, perhaps, the most vacuous of all policies pursued by South Korean presidents: picking up historical disputes with Japan.

Of course, the South Koreans have good reason to be angered by the insensitivity of some Japanese officials to the horrors which their predecessors meted out on Korea during the long decades of Japanese occupation, as well as World War II.

Nevertheless, it is also a fact that successive generations of South Korean politicians have enjoyed baiting Tokyo. This is largely because tensions with Japan are a defining element in South Korean nationalism, a sort of displacement therapy game, allowing them to vent their frustration at their national divisions and other ills which have almost nothing to do with Japan.

And nowhere is this tendency to view Japan as South Korea's implacable foe more evident than in the political camp of President Moon; Mr Roh even tried a decade ago to persuade astonished US government officials that Washington should classify Japan as "a hypothetical enemy".

But this attempt to corner Japan in order to clock up nationalist kudos at home entails an enormous waste of time and resources.

For, far from being an enemy, Japan is South Korea's natural ally and, given China's rise, Tokyo will remain Seoul's friend for decades to come. Mr Moon could accomplish a great deal on this matter by doing precisely nothing; by avoiding falling into the trap of his predecessors playing the "Japan card".

None of this means that Mr Moon is bereft of other policy options. He should launch a dialogue with both the US and Japan about future policy towards North Korea, an even more urgent task given recent indications that North Korea has no intention of stopping its nuclear quest. He can work to attract Europeans and other nations into consultation over the Korean crisis; that could go some way towards counter-balancing the overwhelming influence of the US in this matter. And he must offer an olive branch to China, as well as expand Seoul's contacts with Russia, which is increasingly playing its own game in North Korea.

But beyond that, sticking to the alliance with the US, improving relations with Japan, maintaining and expanding American military deployments, and dispelling any dreams of sunshine engagement with North Korea remain Mr Moon's only viable alternatives.

The South Korean leader must also accept that his country no longer has a first say over managing the North Korean confrontation; this is now a crisis which directly threatens the security of the US and, therefore, the best Seoul can hope for is to have an input into US policy, rather than a right of veto over American choices.

Mr Moon will not be a politician if he does not resent the progressive narrowing of his country's strategic options. Still, he will not go down in history as a great politician if he ignores these realities.