A cancer-stricken single mother had her government financial aid cut off after she raised about $900,000 from crowdfunding websites Give.Asia and Generosity. Her appeal for help to fight cancer and stay alive for the sake of her young son moved many donors.

But not the authorities - who had an insight into her financial background. They deemed she had enough resources after all that fund raising and did not need to be on Medifund and Comcare - government financial aid schemes for the poor which she had accessed.

In her crowdfunding appeals, the woman said she sold off all that she could in her two-room flat and skipped meals so her son could have proper meals.

She also said the immunotherapy she needed was not covered by Medifund or other subsidies, although the hospital she was receiving treatment at declined to confirm this due to patient confidentiality concerns.

Her case, which was reported in July, comes after the Government said it will step in earlier to set the record straight if individuals give misleading or one-sided accounts when appealing for donations online.

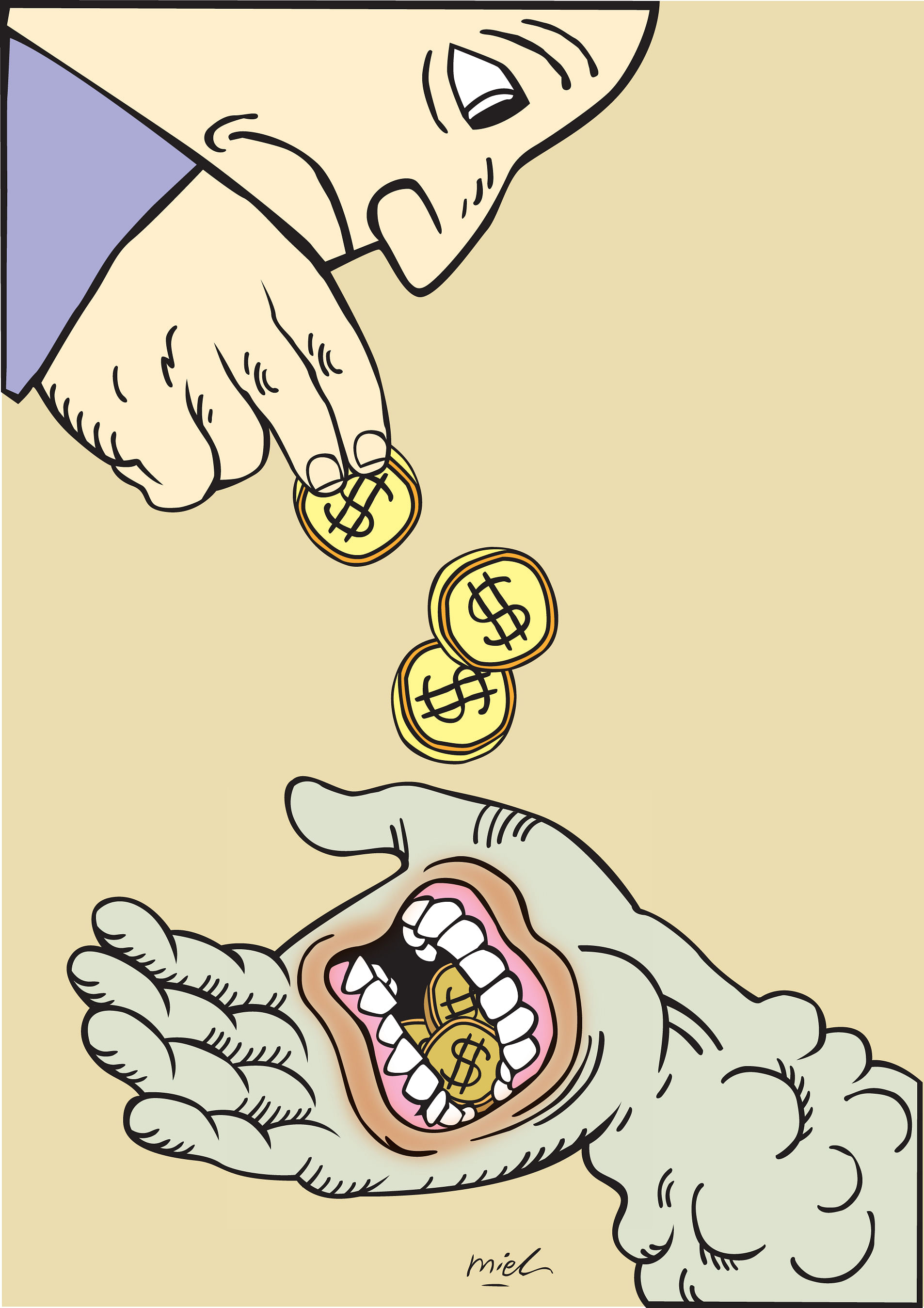

The growing popularity of crowdfunding sites such as Give.Asia, Simply Giving and Generosity is both a boon and bane for the public and the Government.

They allow practically anyone to ask for help online, potentially appealing to the generosity of donors globally.

And it can be easy money compared with the traditional "helping-hand" routes.

There is no need to rely on social workers in charities to assess a situation, for example, or to depend on government financial aid schemes, which have strict eligibility criteria.

All they need to do is share on these platforms their stories, photos, videos and, of course, some proof of the desperate situation they are in. As a result, some have raised eye-popping six-and even seven-figure sums.

For instance, the Singapore parents of three-year-old Xie Yujia, who was born with only part of her oesophagus, raised about $1.2 million to help her get specialist surgery in the United States.

While these sites offer much promise by matching help-seekers with potential donors, they are open to abuse.

In September, Minister for Social and Family Development Desmond Lee said in response to a parliamentary question: "There have been cases where individuals present inaccurate information online to raise funds, including denying that they have received government assistance. Should there be more crowdfunding practices discovered to have exploited the generosity of donors, the public may become sceptical towards worthy fund-raising initiatives."

COMMON BEST PRACTICES

Earlier this month, it was announced that the Commissioner of Charities (COC) is working with key players in the crowdfunding scene to develop a set of best practices for crowdfunding sites.

The new Code of Practice will require the sites to do due diligence to ensure the legitimacy of appeals and to ensure transparency by giving updates on donations raised, among other things. It is likely to be ready in a couple of months.

Crowdfunding sites say they do some checks now, but welcome the new code to ensure a set of common best practices.

For example, Simply Giving, which operates in eight countries including Singapore, does a "100 point check", which is used by the Australian government to fight fraud, and points are assigned to the various types of documentary proof of identity the person can show.

Individuals who want to raise over $5,000 on Simply Giving have to score at least 100 points to ensure the legitimacy of their appeal, said its chief executive Nikki Kinloch. She added that it has not found any fraudulent fund-raiser so far here.

Give.Asia, started by two National University of Singapore graduates as a social enterprise, has said it has staff who constantly monitor fund-raisers to ensure that they are legitimate and will ask for more information if they find anything questionable, among other safeguards.

In May, a conman was reportedly raising funds on Give.Asia for a dead baby when the parents were not seeking help. The site shut down the fund-raiser and returned the money to donors.

Ms Grace Fu, the Minister for Culture, Community and Youth - under which the COC's office comes - said the new code is not likely to be mandatory.

She said when announcing it: "We would like to work with the industry on the level of regulation, so as not to impede the growth of this online sector but, at the same time, ensure that the risks are managed."

If the new code is not mandatory, one concern is that it will lack the bite to compel crowdfunding platforms to adopt the recommended best practices.

One suggestion is to make public - and actively highlight - sites that adopt best practice and those that do not. This way, the public is better informed and can decide the appeals on which sites it wants to support.

In this, the COC can take a leaf from the Code of Governance for Charities and Institutions of a Public Character, which was first introduced in 2007.

That code is also not mandatory, but charities have to comply with best practice or explain any non-compliance. Charities also have to submit an evaluation checklist on governance measures, which is reflected on the COC's website.

A new best practices code specifically for crowdfunding sites is needed because the sites face unique challenges - for example, in verifying the financial background of individuals seeking to raise funds.

So it will be helpful for donors to know what are the common guidelines these sites are expected to follow and they can decide if they still want to give.

The COC Office told The Straits Times that once the code is ready and adopted, it will publish a list of online platforms that subscribe to it on its website, the Charity Portal.

The office will also ramp up public education on informed giving so that donors know what information to look for and what questions to ask before giving. It will also highlight crowdfunding platforms that subscribe to the code during these education initiatives.

SERVICE FEES CHARGED BY CROWDFUNDING SITES

The new code is a step in the right direction, as the onus should be on the crowdfunding sites to do the necessary checks to prevent abuse.

After all, many charge a service fee - often a cut of the sums raised - on top of transaction fees charged by banks or credit cards for these transactions.

The exceptions include Giving.sg, which is run by the National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre, and Give.Asia, which depends on "small optional donations from donors to help cover our operating expenses", says its website.

At Simply Giving, the service fee is 5 per cent of donations received, plus another 2.08 per cent for the bank transaction fee.

At Go Get Funding, it charges 6.9 per cent of the funds raised, including a 2.9 per cent payment processing fee, its website said.

So assuming a crowdfunding site charges a service fee of 5 per cent, it gets $5,000 out of every $100,000 raised.

With easy access to crowdfunding sites here, there is a worry that some individuals may abuse the public's generosity as an easy way out of their difficulties - instead of relying on hard work, thrift and family as the first line of support that Singaporeans are known for.

Browsing through these sites, the appeals from individuals range from those with hefty medical bills to pay to people looking for help to settle their debt or to travel overseas for various reasons.

For example, the family of a seven-year-old girl suffering from heart failure appealed for help on Give.Asia to pay her hefty medical bills to help her live. Over 3,000 people donated more than $500,000.

A group which rescues street dogs asked for help to pay a labrador retriever's medical bills. They raised $1,025 on Simply Giving for the dog suffering from bone cancer.

A young Singaporean wanted to meet his foreign girlfriend in America before he enlists in the army next year. Over 30 people gave him a total of about $500 on Go Get Funding, another crowdfunding site, to fund his travel expenses.

And considering that these individuals can crowdfund on as many sites as they wish, the danger of using such sites as a quick and easy way out of their financial woes cannot be dismissed.

Then, this also adds to the divide between the tech-savvy who have access to these sites and who are willing to share their stories - and those who don't.

Crowdfunding comes with much promise but also some perils. The key is to unlock its promise, yet keep the perils at bay.