It's a jungle out there in the Garden City. As Singapore's greening efforts take shape, more reported cases of run-ins between man and beast - some with serious consequences - are emerging.

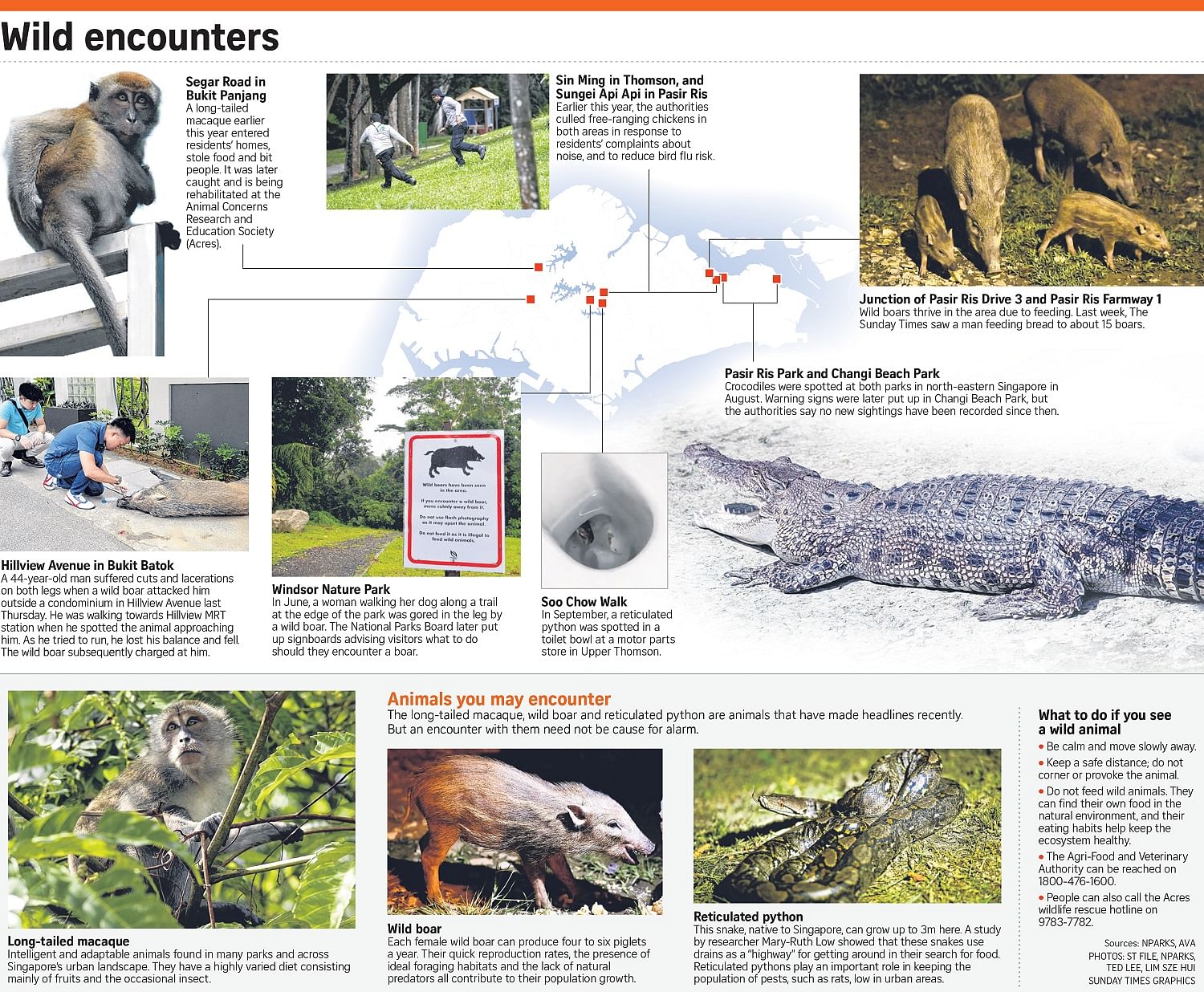

Monkeys have been terrorising people in their homes. Wild fowl have caused a flap. And then, just last Thursday, a wild boar charged at a man walking past a condominium in Hillview Avenue to the MRT station. The 44-year-old man suffered cuts to his legs.

Wild boars were also in the spotlight last month when five people were taken to hospital after vehicles collided with the animals.

A long-tailed macaque, meanwhile, wreaked havoc for months in the homes of Segar Road residents in Bukit Panjang, entering units and biting people. It took a team comprising wildlife rescue group Animal Concerns Research and Education Society, the Wildlife Reserves Singapore and the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority (AVA) to catch it in May.

While some marvel at the weird and wonderful wildlife in urban areas here - WhatsApp groups have been created to alert nature enthusiasts about otter sightings, for example - unpleasant animal encounters are upsetting others.

Auditor Anita Srinivasan, 38,who lives in a condo close to where Thursday's boar attack happened, says: "I'm worried for my kids. The lights at our walkway are always dim, so it's hard to see animals."

All this highlights the importance of Singapore's animal management strategies.

Once, it emphasised culling as the immediate solution to complaints about wildlife, but things are changing, notes mammal researcher Marcus Chua from the National University of Singapore's (NUS) Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

Just last month, a working group on the long-tailed macaque was launched to look at reducing human-wildlife conflict. One aim is to develop pre-emptive measures such as public education, says group co-chairman and primate scientist Andie Ang. The group consists of experts from government agencies, scientists and non-government groups,

How big is the problem and what does this new strategy involve? With human-wildlife encounters expected to rise, is it the right way forward?

AWASH WITH WILDLIFE

Figures from AVA show a growing number of reports made about animals over the years, with feedback relating to monkeys and snakes topping the list.

AVA received 770 reports on monkeys in 2014. Between January and September this year, this grew to 1,170. For snakes, the figure was 610 in 2014, and 1,100 for the first nine months of the year. As for wild boars, AVA received 30 wild boar-related reports in 2014, and 190 between January and September.

What is drawing wildlife into Singapore's urban spaces? No studies have been done to conclusively determine this. But experts point to several reasons.

First, it could be a consequence of Singapore's City in a Garden drive.

The Republic outshone 16 cities in a recent study on urban tree density by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the World Economic Forum. Almost 30 per cent of Singapore's urban areas are covered by greenery. This puts Singapore ahead of Sydney and Vancouver, which tied for second place with 25.9 per cent.

"Planting up the landscape can improve or create a habitat. It may also create suitable linkages or refuge for wildlife between existing habitats. Some mammals that have benefited are the plantain squirrel and long-tailed macaque. It is possible civets use them too," says NUS' Mr Chua.

The oriental pied hornbill - an endangered bird native to Singapore - is practically the poster child for the Republic's greening efforts. The species was extinct here for nearly a century, but recolonised Pulau Ubin in the early 1990s.

Due to an extensive reintroduction programme, the hornbills have gone on to spread more widely on mainland Singapore - even showing up at urban condominiums, such as Country Park Condominium in Bedok.

Second, the lack of predators could cause some animals to proliferate. "Wild boars' quick reproduction rates, the presence of ideal foraging habitats and the lack of natural predators all contribute to their population growth," says the National Parks Board (NParks) on its website.

On the other hand, urbanisation has a "push" factor, too. Dr Lena Chan, senior director of NParks' National Biodiversity Centre, points out: "When we start urbanising, the natural land bank becomes smaller."

The squeeze factor extends beyond Singapore. "Developments in the region could be 'squeezing' wildlife and reducing their habitat, and so they leave in search of other places," says Dr Shawn Lum, president of the Nature Society (Singapore) and a senior lecturer at Nanyang Technological University's Asian School of the Environment. Crocodiles, for example, swim freely in the Johor Strait, the channel of water separating Singapore from Malaysia.

They are a common sight at the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, but rarely seen elsewhere. However, in August, crocodiles were spotted at parks in Pasir Ris and Changi. It led the authorities to put up warning signs at Changi Beach Park.

ANIMAL INVASION?

Is the resurgence in wildlife getting out of hand?

Singapore has been awake to the issues and moved to address this. But stop-gap measures to keep animal populations in check, such as culling, have been controversial.

-

ESM Goh's advice on dealing with wildlife

When the authorities culled free-ranging chickens in Sin Ming and Pasir Ris earlier this year over concerns about public health and complaints about noise, many feathers were ruffled.

People who questioned the need to kill the birds say the risk of bird flu - which the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore had noted was endemic in the region - was not immediately obvious.

However, residents affected by the crowing say the birds are a nuisance and should be got rid of.

The incident highlighted the divide between those tolerant of wildlife in Singapore and those who are less so.

Soon after the debate erupted in February, Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong, an MP for Marine Parade GRC, posted a photo of birds on Facebook, saying: "This junglefowl came a-calling. Some months ago a family of junglefowls visited and left. Hope this one will take up permanent residency in my garden. It will be safe from culling."

Insight approached Mr Goh for his advice on dealing with wildlife. He said: "Learn to live with them and enjoy seeing them. Most animals are not dangerous and will keep a safe distance from human beings. I saw a civet cat once on the roof of my house. It was fascinating as I had not seen one before. There are also squirrels in my area. Fortunately, no monkeys!

"The wild animals we have in Singapore are generally small and can thrive in our woods and Garden City. They enrich our environment, making Singapore a natural city and not a barren one. The presence of small, wild animals is a tribute to our ability to balance urban living with nature."

He added: "Occasionally we may run into larger and potentially aggressive animals such as wild boars, snakes and crocodiles. They are best left alone and reported to the authorities who are trained to handle them safely. Not worth putting oneself at risk or stressing the wild animal for the sake of a selfie or video."

The outcry over the AVA's culling of free-ranging chickens earlier this year highlighted this. Primate researcher Sabrina Jabbar, from conservation group Jane Goodall Institute (Singapore), or JGIS, says culling merely leaves a vacuum for another animal to fill.

So to better manage animal populations in the long run, more data about ecology and behaviour is needed. In other words, strategies to manage the problem need to be backed by sound science.

The Government has already adopted such an approach. For example, research into stray dog and urban bird populations is now taking place. The dog study, commissioned by the AVA, aims to establish an estimate of the stray dog population size, and to understand ecological and biological aspects such as their mortality and reproductive rates. The study could determine the effectiveness of the trap-neuter-release method of controlling the stray dog population, which animal welfare groups perceive to be a more humane strategy than culling.

But such studies take time. The dog study, for instance, is a three-year one which started in 2015. And it may be difficult to convince those affected by the antics of wild animals to have patience.

What is needed is a preventive solution that tackles the root of the problem, instead of a reactive one. This is something the authorities, scientists and non-government groups are moving towards.

NIPPING THE PROBLEM IN THE BUD

Key to this preventive strategy is educating people on how to interact with wildlife. The setting up of the long-tailed macaque working group is one measure.

The AVA is also working with JGIS on plans to conduct wildlife briefings for residents living near the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve to educate them on how they should behave when encountering animals such as the long-tailed macaque.

AVA's deputy director of its wild animal section, Mr Jonathan Ngiam, says: "Tips include not feeding wildlife, harvesting fruit from trees within the compound wherever possible, or closing windows during the timings when the macaques are expected to appear."

This is sound advice, as conflicts between humans and animals occur mostly over food.

It was the case for the Segar Road monkey, which had been fed by residents there. People feeding wild boars have also resulted in large herds of them gathering in areas such as Pasir Ris.

When residents or visitors to a nature area start to feed wildlife, either deliberately or unintentionally, it can result in the animals associating humans with food. This can cause them to seek out humans in hopes of getting a treat, says Ms Jabbar.

High availability of food makes female macaques give birth at a rapid rate, thus leading to a possibility of population rise. "Their rate of reproductive success depends on food availability, so the availability of food could make them hit that threshold faster," notes Ms Jabbar.

As Mr Tay Kae Fong, president of JGIS, says: "For an effective measure to be successful, we need to have all sides get on board. Apart from environment and animal groups, residents near hot spots, parkgoers and the Government will all need to jump in."

Segar Road resident Hetty Karim, 39, an instructional assistant at the Singapore American School, agrees: "For me, it's simple - the monkey is here for food. If you're scared of it, close the window."

National University of Singapore sociologist Tan Ern Ser says there has been a value shift towards greater concern for environmental issues and wildlife. But, when it comes to wildlife that poses a nuisance, there may be a contest of approaches on how to deal with it - to tolerate or exterminate.

Tolerance of animals may take some time to build. But learning the dos and don'ts of interacting with wildlife - by not feeding or provoking them, for instance - is not difficult. Says retired businessman Russell Ng, 68, who is visited by long-tailed macaques almost every day: "It's not rocket science to figure out how to make them go away - they won't come if there's no food for them."

•Additional reporting by Raffaella Nathan Charles