At first glance, Berlin, Barcelona and Singapore do not seem to have a lot in common. A closer look, however, will show that all three aspire to become "smart cities" in order to increase the quality of urban life.

This was confirmed during a study trip to Germany and Spain that 28 Singapore Management University (SMU) undergraduates and I went on recently.

I had themed the trip "Living in Smart Cities: Innovation and Sustainability in Berlin (Germany) and Barcelona (Spain)". The key objective was to expose Singapore youth to selected smart city concepts and practice approaches in two great European cities with reference to smart city dimensions such as the economy, governance, people, living, mobility and the environment.

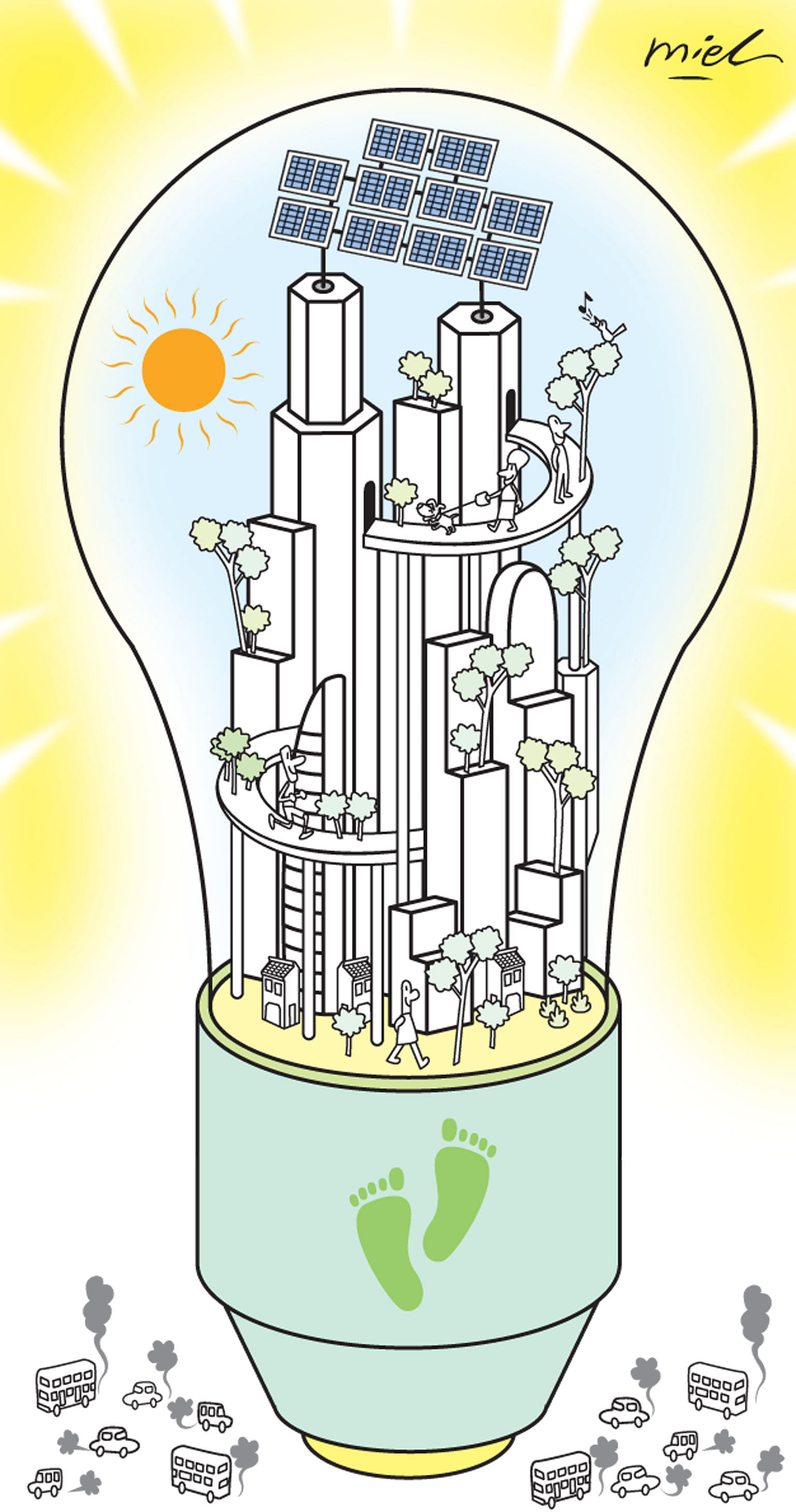

Smart cities use information and communication technologies to become more intelligent and efficient in the use of resources so that they can provide more relevantservices to their citizens for a higher quality of life.

They aspire to significantly reduce their environmental footprint via a sustainable built environment, zero-carbon strategies, intelligent mobility systems and renewable energy supply.

BERLIN: URBAN SOCIETY PARTICIPATION

Rather than start off by scrutinising Berlin's smart city achievements and ambition towards becoming a "sensorised" city, we began our journey with a long walk on the runway of its former Tempelhof airport (built at the beginning of the 1920s) on a sunny afternoon.

The goal was to appreciate the importance of participatory urban development in turning this site - which became famous during the Berlin Blockade of 1948-1949, when the Allied forces responded to Russian attempts to take over all of Berlin with the so-called Berlin Airlift - into a public park.

In seeking to create a smart(er) city, Berlin's administration is in the process of further digitising business processes and is to roll out more e-government projects. Accordingly, a novel e-participation project was conducted with several stages, such as brainstorming, dialogue and a "call for ideas" (including several airport events, workshops and open councils) to build a broad consensus regarding the use of the land of the former airport, which was closed in 2008.

The project contributes to the vision of Berlin as a climate-neutral city. In size, it is 386ha, and is now one of the world's largest, centrally located open spaces for public use, featuring a 6km-long cycling, skating and jogging trail, a barbecue area, a huge communal garden, a dog-walking field and picnic sites for visitors.

Tempelhof also houses refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere.

SMART CITY, SMART ENERGY

We also visited the 5.5ha Euref (European Energy Forum) campus in Berlin-Schoneberg, a forward-looking "model project" on a former industrial site which has been redeveloped into a business, research and education hub.

Euref hosts a variety of clean- energy-related companies and organisations such as the Green Garage, a cleantech accelerator that helps start-ups turn the climate challenge into a business opportunity.

Another tenant is Schneider Electric, a globally-operating specialist in the field of energy management and automation, which provides integrated solutions for energy and infrastructure, industrial processes, data networks and buildings.

At its showroom, ZeeMo.base, the students gained deeper insights into the importance of zero-emission energy (that is, energy that emits no waste products that could be harmful for the environment or the climate) and smart electricity distribution systems. Via a micro smart grid demonstrator, they were exposed to different energy management scenarios while watching real-time monitors displaying varied consumption patterns and energy flows of both renewable and non-renewable energy sources ranging from solar to nuclear.

The visit was instrumental to appreciate the reasons behind Germany's so-called "Energiewende" (energy transition) policy - that is, the transition to a low-carbon, environmentally sound, reliable and affordable energy supply.

At Berlin's Adlershof Science City, the students continued to explore what it takes in terms of research and innovation to become an energy-efficient city. The science park - one of the most successful high-tech sites in Germany - is home to over 1,000 companies and scientific institutions. About 16,000 people work here on an area of 4.2 sq km with about 6,500 students.

As coal-fired generators and nuclear power plants are phased out, Germany continues to push forward the change towards renewable energy sources such as wind, photovoltaics and biomass.

Ambitious goals include greenhouse gas reductions of 80 to 95 per cent by 2050 and a renewable energy target of 60 per cent by 2050. Adlershof's expertise in the area of energy efficiency is a powerful driver of this mega change. It also supports start-ups in the field of smart energy and Internet of Things, exploiting new possibilities to connect information and communications systems, buildings and (wireless) infrastructural elements such as smart lighting systems.

INNOVATION DISTRICTS, MAKER SPACES

Innovation districts such as Adlershof play an important role in a smart city.

A famous Spanish example is 22@Barcelona (or Districte de la innovacio), an urban renewal area in Barcelona's former industrial area of Poblenou (historians refer to it as the "Catalonian Manchester").

Its massive transformation into an urban technological and innovation district with leisure and residential spaces was triggered by the Olympic Games in 1992, and subsequently accelerated in 2000 by a new urban planning ordinance approved by the Barcelona City Council.

As explained during a meeting with Mr Antoni Vives, former deputy mayor of Barcelona, its Smart City Strategy contains 22 integrated "habitat" programmes in areas such as data-driven water and waste management, smart mobility, innovative healthcare and so forth.

An interesting example of a ground-up, community-based and citizen-centric smart city project is Barcelona's so-called Fab Ateneus Network, which offers spaces for "creating collaborative, socially innovative outcomes that help to manage to transform peoples' urban surroundings in a sustainable manner".

The network's mission is to nurture an "innovate and create culture" in different boroughs of Barcelona based on collective creation, innovation and participatory bottom-up initiatives.

La Fabrica del Sol, a facility for environmental education supported by the Ecology, Urban Planning and Mobility Department of the Barcelona City Council, has a similar socially innovative co-creation vision.

The renovated building has various environmentally friendly features such as a pergola for solar collectors and photovoltaic panels. Equipped with 3D printers, laser-cutting and stitching machines, power tools, computers and more, La Fabrica del Sol represents an organic space for the exchange of ideas, joint learning and making things with a view towards meeting both the challenges of sustainability and needs of the immediate neighbourhood.

Visits to CaixaBank, one of Spain's most innovative banks and an early fintech pioneer, and the Centre for Innovation in Cities at Esade Business School concluded the formal visit programme to Barcelona.

TAKEAWAYS

The smart city movement in Berlin and Barcelona turned out to be diverse, alive and kicking (and difficult to grasp fully in a few days), with Barcelona, arguably, being the more attractive urban destination, not least because of its rich cultural sites such as Gaudi's Familia Sagrada, authentic urban street life and Mediterranean climate.

"Open urban innovation", "Internet of Things", "open data", "the maker movement", "sharing economy", "politics of space", "travel on demand" and the "use of empty city plots by civil collectives as smart platforms to create community gardens and to share books or tools" emerged as topical concerns of experts and citizens we spoke to.

What impressed me the most?

In Berlin, it was the collective determination and practical capacity of start-ups to fight climate change and to monetise that agenda on the basis of smart business models (we also noticed while exploring the former Tempelhof airport runway that Berliners seemingly do not use their smartphones during their leisure pursuits).

Most notable is that the collective commitment to pursue solutions to climate change extended across all the sectors - from the state, to start-ups and the business sector, to individuals and community groups.

In Barcelona, we enjoyed the city's walkability, which - in combination with a pleasant environment - represents an essential component of smart urban (integrated) mobility systems.

It also enhances quality of life and one's health, providing a safe, pollution-free and age-friendly environment.

And there were times when I asked myself whether it would make sense to integrate communal maker spaces a la La Fabrica del Sol into our Housing Board heartland.

After all, what makes a city truly smart is not just its array of sensors, or even its smart energy grid. It is the ground-up efforts of people getting together to create a future for themselves that makes a smart city home.

- Thomas Menkhoff is professor of organisational behaviour and human resources at the Lee Kong Chian School of Business, SMU, and academic director of SMU's Master of Science in Innovation programme.