Three months ago, I stood at the World War II memorial in Pearl Harbour, looking down at the hull of the sunken USS Arizona, the battleship on which more than 1,100 American sailors died in a surprise Japanese attack in December 1941, leading to US involvement in the war.

Elsewhere on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, including its famed Waikiki beach strip, a different kind of invasion from the Land of the Rising Sun was under way: Hotels were at full capacity, thanks to thousands of Japanese tourists.

At the US Pacific Command headquarters, the head of the Pacific Fleet, soon to be given the entire command, was Harry Harris, a Japanese-American born in Yakasuka.

Seventy years after a terrifying hard rain fell over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, delivered by United States bombers, Japan has embraced the nation that vanquished it. Annual ceremonies for the bombings' anniversaries on Aug 6 and Aug 9, respectively, mark the suffering. Newspapers carry special pullouts. Interestingly, there is little rancour about the perpetrator of the world's only nuclear attack.

Elsewhere in the world, though, people do question: Was the second bomb necessary? Could the first not have been detonated over Tokyo Bay, thereby making clear the immense force at the command of the Allies, but avoiding the thousands of deaths and suffering that would continue for decades?

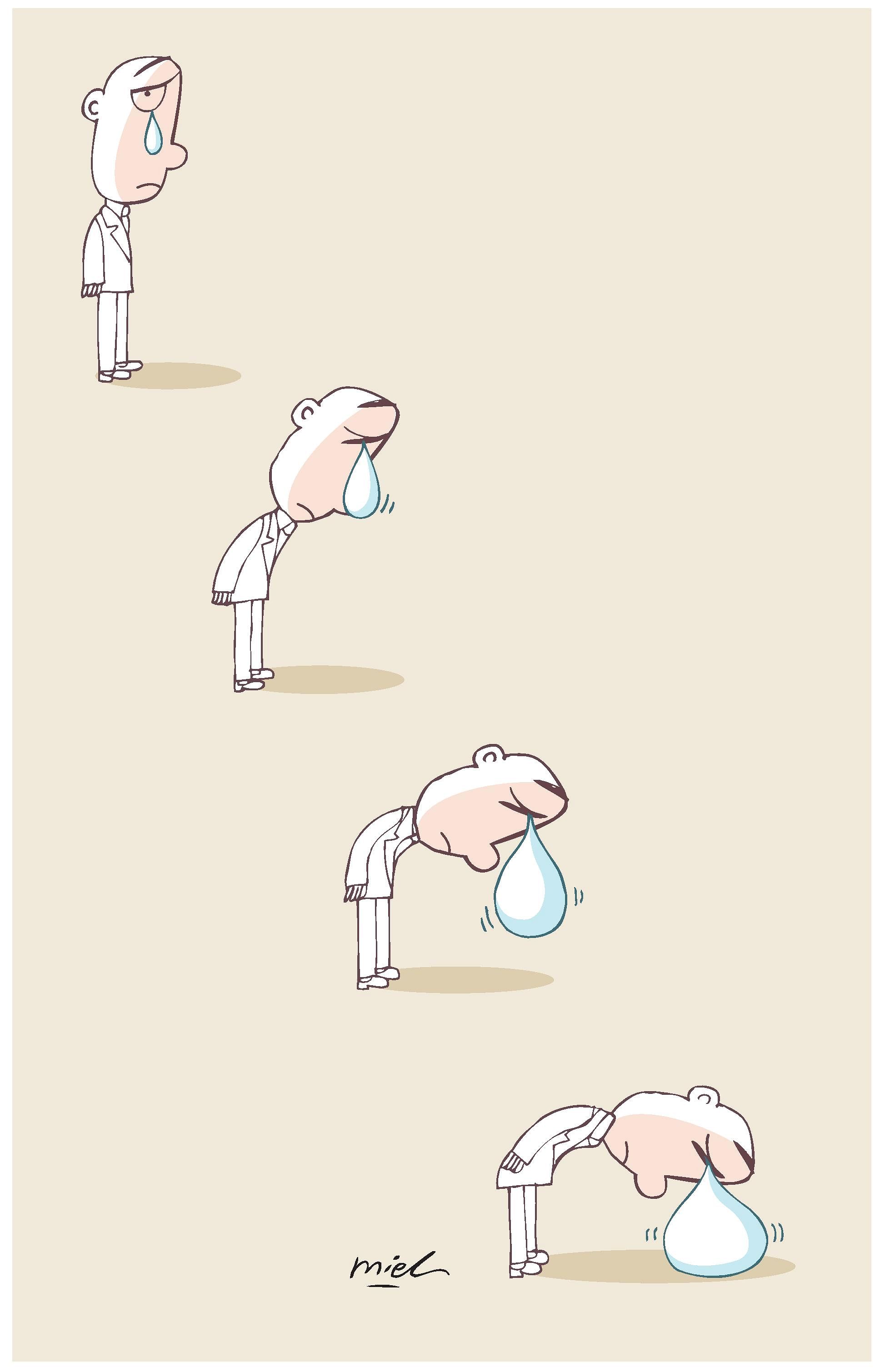

Japanese themselves keep their head lowered, aware of the damage and the suffering they brought to Asia.

Now, as the Aug 15 anniversary of the end of the Great War approaches, Asian eyes are fixed again on Japan and on Mr Shinzo Abe, its youngest post-war prime minister. In most years the anniversary would have passed with cursory curiosity. But these aren't ordinary times and this is no ordinary anniversary - the 70th since the war was officially over.

Besides, Mr Abe is not your ordinary Japanese leader.

Since returning to power in 2012, he has set a frenetic pace in altering Japan's security profile. He established a National Security Council, spelt out a security strategy, revised the policy on arms exports and "collective self-defence" and moved Bills to allow Japanese troops to go to the aid of allies, even when Japan is not directly under threat.

Earlier, he surprised many by deciding to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, the economic brick of the larger edifice of the US rebalance to Asia - something with which Mr Abe has identified himself completely.

Yet, despite the approval he seems to crave from Washington - he has an amazing proclivity to grant interviews to American newspapers while avoiding requests from Asia - he ignored American advice and went ahead to pray, controversially, at the Yasukuni Shrine, a memorial for Japan's war leaders, including a handful of acknowledged war scoundrels.

Mr Abe insists he did it to remind himself and his nation of the terrible effects of war. Sceptics say he is artfully playing to a nationalist fringe that's tired of apologising for the outrage and looks askance at the one-sided versions of history taught to Chinese and Korean students. Many tend to overlook that some of his security initiatives were inherited from his predecessor, Mr Yoshihiko Noda.

Either way, all these are useful sticks to beat Mr Abe with.

But what makes him even more interesting a study is that, unusually for a politician, he has appeared willing to absorb knocks on his popularity and public standing to pursue his vision. The security Bills, unpopular with significant sections of the people, thousands of whom protested in the streets of Tokyo, has cut his approval ratings to less than 40 per cent. Yet he went on to make another unpopular move, restarting the nuclear reactor at Fukushima.

How will this feisty man speak today? The world is watching.

WHAT WILL ABE SAY?

In the Korean peninsula, which was occupied by the Japanese from 1910 to 1945, and in China, whose war with Japan from 1937 caused the highest number of battle deaths of the 20th century in Asia, there is a sense of trepidation.

Elsewhere, even in nations such as the Philippines that went under the Japanese jackboot but now fear an assertive China, there is the thrill of anticipation: Will Mr Abe ignore the sentiments of the Koreans and the Chinese and mute the apology for the war that many expect him to do? Will he play down Japan's role in the atrocities, including the slave prostitution imposed on Korean women by the Imperial Army? Certainly, a good number may not mind.

Mr Abe has kept us guessing but among the several factors that will determine the content of his statement, a few are key.

One is the Japanese understanding of early 20th century history. The Eminent Persons Group that reported to Mr Abe last week, for instance, sets Japan's actions in the first half of the 20th century against the backdrop of the tremendous technological advances in the West that spurred colonisation by Western countries. That included US rule in the Philippines. Indeed, the group credits Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 not only for stopping Russian expansionism, but also fuelling the anti-colonial movements of Asia.

Some parts of Asia, such as India, may not disagree with this interpretation. The Singapore memorial for the rebel Indian National Army, which was raised in South-east Asia and fought the British in Burma and Imphal alongside Japanese forces, is testimony to another experience in Asian history. Needless to say, many more will not agree with this.

The Japanese also feel that some of the recent demonisation they suffer is on account of domestic pressures on the Chinese and South Korean leadership.

After the Tiananmen Square incident and the Soviet collapse, the question of sustaining single-party rule under a socialist system gained salience with the Chinese Communist Party and patriotic education became a vehicle to reinforce party legitimacy. The wars with Japan became a central element in that education. Likewise, they interpret South Korea's stiffening attitude to the dip in popularity of President Park Geun Hye, who is facing re-election in two years.

Besides, Japan has to be also judged against its post-war actions. Like Germany, its Axis partner in Europe, Japan has made significant non-military contributions in the post-war decades.

Its Flying Geese model of development, with itself as lead goose, helped create Asia's Tiger economies and the East Asian economic miracle. Since then Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka was met with boos and jeers in Jakarta and Bangkok in 1974, it has also made local production a mantra and helped with large-scale technology transfers, changing its face from a mercantilist exporter to a true development partner.

Even China has gained; Matsushita was one of the earliest investors in the mainland, continuing to pour in money even after Beijing was in the international dog house in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square incident.

To further assuage this region and spread balm on its painful memories, the Fukuda Doctrine was promulgated by Mr Tanaka's successor, expressing Japan's determination to not become a military power. Without question, Japan has backed its claims of good intentions with words and action.

Yet, like the Second Voice in Coleridge's Rime Of The Ancient Mariner, who intones that "The man hath penance done, And penance more will do", Japan is not allowed to shake off its albatross.

To insist that Japan walk around with an apology in its pocket is therefore an unfair expectation.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, visiting Japan earlier this year, clearly told her hosts that her nation had "squarely faced up to the past". Then she surprised her audience by also noting that "there was tolerance on the part of our neighbour (France)".

It is all very well to say, as the Koreans tend to do, that it is up to the victims, not the aggressor, to call a halt to the apologies Japan has to make. But at some point, it has to come to an end. As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in May at the Shangri-La Dialogue, the history of the war should not be used to put Japan on the defensive, or to perpetuate enmities into future generations. Only with largeness of heart can all sides move forward.

As the hour for his statement approaches, there is apprehension that Mr Abe may avoid talking of aggression and instead use formulations such as "causing harm to various countries, largely in Asia, through a reckless war".

That would be plain silly. Mr Abe will do well to unequivocally endorse the apologies offered by his predecessors and fess up to Japan's dark past of aggression. Perhaps he could add a few original words of remorse.

But he must also make clear that the apologies cannot be endless. Once done, he can turn back to his task of stitching up Japan's security for future generations.