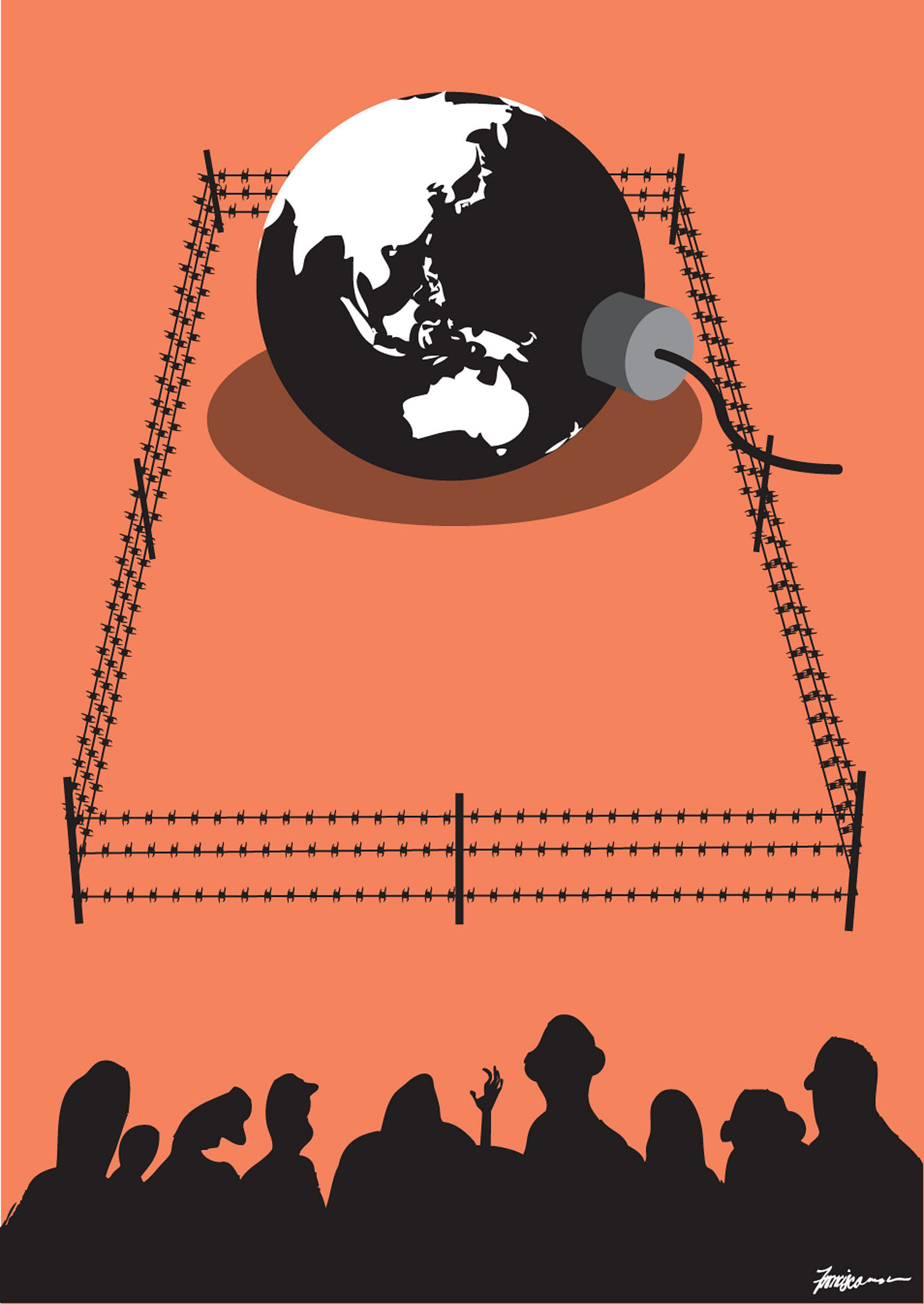

Not since the landlocked Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan swept out its Nepali-speaking Hindu population in the late 1980s has Asia witnessed as relentless an action against a minority group as seen lately in Myanmar. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has called the sustained drive to push Rohingya Muslims out of Myanmar a "textbook example of ethnic cleansing".

Their number once estimated at 1.1 million, more than two-thirds of Myanmar's Rohingya Muslims have been forced to leave, some arriving after dangerous crossings by boat in South-east Asian nations while the vast majority simply trekked across the land border into Bangladesh.

There, an estimated 700,000 are sheltered in extremely dismal conditions. Half the refugees arrived in just the past three weeks. Food is short and disease threatens.

Elsewhere, Malaysia is estimated to have 60,000 Rohingya refugees registered with the UNHCR. India has fewer but still significant numbers of Rohingya.

Manfully, Bangladesh has struggled to cope with the influx, its Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina Wajed, invoking memories of the 1971 Liberation War when 10 million of her people streamed into India to take refuge from the jackboots of the Pakistan army fighting to hold on to the eastern half of the country.

The latest exodus from the Rakhine was triggered by the outrageously heavy-handed retaliatory response of the Myanmar military to a spate of attacks on police and military camps around Aug 25 by machete-wielding Rohingya owing allegiance to the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (Arsa).

Arsa, which also goes by the Arabic name Harakah al-Yaqin, is said to be led by a Rohingya man born in exile in Karachi and raised in Mecca.

Ten soldiers, a policeman and another government official died in those attacks. The state's response has been so brutal that about 40 times that number of Rohingya have been eliminated and nearly 200 Rohingya settlements torched.

Today, thanks to the actions of the Tatmadaw, as the Myanmar military is known, a heat map of Islam-related hot spots in South-east Asia would instantly light up two corners - Marawi in the south-east of the region and the Rakhine in the north-west.

Naturally, the question arises: Where will the red flashes go up next?

And that's the part about which all of South-east Asia needs to be on guard.

Last weekend, in an article published in Al-Qalam, the official mouthpiece of the Jaish-e-Mohammed terrorist group, JEM founder Maulana Masood Azhar spoke of a new awakening in the Muslim world to the situation in the Rakhine, and called for urgent action. Myanmar, warned the Pakistan-based Azhar, would soon hear "the thudding sound of the footsteps of its conquerors".

Azhar's words are considered the first substantial call to arms by an Islamist leader over the Rohingya matter. Although the JEM and its predecessor, Lashkar-e-Toiba, have largely confined their activities to the Kashmir area - the reason it is thought to have covert backing of the Pakistani state - it nevertheless is a significant development.

BIGGER GAME

Arsa, which Myanmar now calls a terrorist organisation, has denied it has external links, or is interested in anything but protecting the rights of Rohingya. And while its actions are generally accepted as a response to state repression, certain aspects of the operations are deeply disturbing because they point to a bigger game.

For instance, the attacks on police - and Arsa's subsequent promise to call off the violence - are reminiscent of the early days of the Tamil insurgency in Sri Lanka's north, when militants actively worked to polarise the community.

To cite just one example, the July 1983 massacre of Tamil prisoners in Colombo's high-security Welikade Prison is now regarded as one of the key trigger points of the full-scale civil war that was to follow in Sri Lanka. Sinhala prisoners, with the jail authorities looking the other way, turned on Tamil inmates with fury, killing more than 50.

Those riots were touched off by reports that 13 Sinhala soldiers had been killed by Tamil militants in Jaffna the previous night.

Time and time again during that long-running war, Tamil militants appeared to be ready for talks, or a truce, only to redouble their efforts after a pause. For this reason, Arsa's recent promise to end armed attacks will probably be treated with a measure of scepticism by those who study insurgencies, or are tasked to handle them.

In fact, the overwhelmingly brutal state response such as what Myanmar rolled out plays to the advantage of those who sponsor insurgent or terrorist violence because it provokes even the timid, the meek and the fence-sitter to turn against the state in indignation and anger. This is why it is important that the Myanmar state not lose its head as it goes about tackling the insurgency.

Indeed, if the motive for the Aug 25 Arsa attacks was to cynically widen communal feelings beyond the Rakhine state, it may just be succeeding. Communal feelings are spreading in Myanmar, beyond the Rakhine. Last Sunday, a Muslim butcher was surrounded by a mob in central Myanmar's Magway region. And outside Myanmar, as the Rohingya issue becomes a full-fledged humanitarian crisis, passions are being stoked in several countries.

South-east Asia's two largest Muslim states, Indonesia and Malaysia, both of which are approaching election season, need to be particularly mindful. The Rohingya's plight is big news in the Muslim world and resonates with the middle class and hardline Islamists. Many politicians have seized on the issue and made it their own. As Dr Zachary Abuza of the National War College in Washington pointed out recently, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) has begun to refer to the Rohingya in its media.

Others recall that the Indonesian authorities have broken up two terrorist plots by pro-ISIS militants to blow up the Myanmar embassy in Jakarta. Two of those arrested in 2013 - Abu Arif and Abu Shafiyah - confessed to being members of the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation, which seeks to create an Islamic state in Myanmar's Arakan region. Al-Qaeda's leadership has urged Muslims to travel to Myanmar and help the Rohingya in whatever way they can.

MORE HUMANE

Elsewhere in South-east Asia, the authorities have rounded up several Bangladeshis with ISIS sympathies. Even if they are predominantly a peaceful bunch whose only mischief is to ensnare local women occasionally, it is impossible to ensure that each one of them is insulated from militant ideas, as Singapore's experience has shown. Malaysia alone is host to some 350,000 Bangladeshi guest workers.

Dr Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury, a former foreign minister of Bangladesh now with the Institute of South Asian Studies, says he worries that the large refugee camps in his country could turn out to be breeding grounds of extremism in the manner that Afghan refugees who settled in Pakistan turned that country into a hotbed of terrorism.

"Once the Rohingya situation turns from resistance to insurgency, it becomes difficult to handle," he says.

The spillover from the Pakistan-based resistance to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan continues to this day. Indeed, Pakistan itself has been one of the worst victims of terrorist violence, a situation that only now has started to ease. In the meantime, Bangladesh, once described as a "basket case" of poverty, has drawn level with Pakistan in per capita income, thanks to its relative stability.

At a time when Asia has so much to worry about by way of slowing trade, disruptive economics and geopolitical risk, Myanmar threatens to be the next international migraine. It can help itself, and its neighbourhood, by taking a more humane approach to the Rohingya and accepting the vast majority of those who fled and their return to their homes in territory earmarked within the Rakhine state.

As the next big frontier market after Vietnam, Myanmar is shooting itself in the foot just at the time that the world had begun to turn to it with investments and trade.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi's decision to cancel a trip to New York for the UN General Assembly suggests that she is fully aware of the embarrassment that awaits her if she steps out of her country, and the scrutiny she will be subject to. Ms Suu Kyi may be bound by the Constitution to bend to the military on security matters but it is time she at least found her voice to say the right things.