The planned move by the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) to build new facilities to house migrant workers who are mildly ill or no longer infectious is timely.

Manpower Minister Josephine Teo said on May 1 that the move was necessary to minimise the risk of recurring transmission.

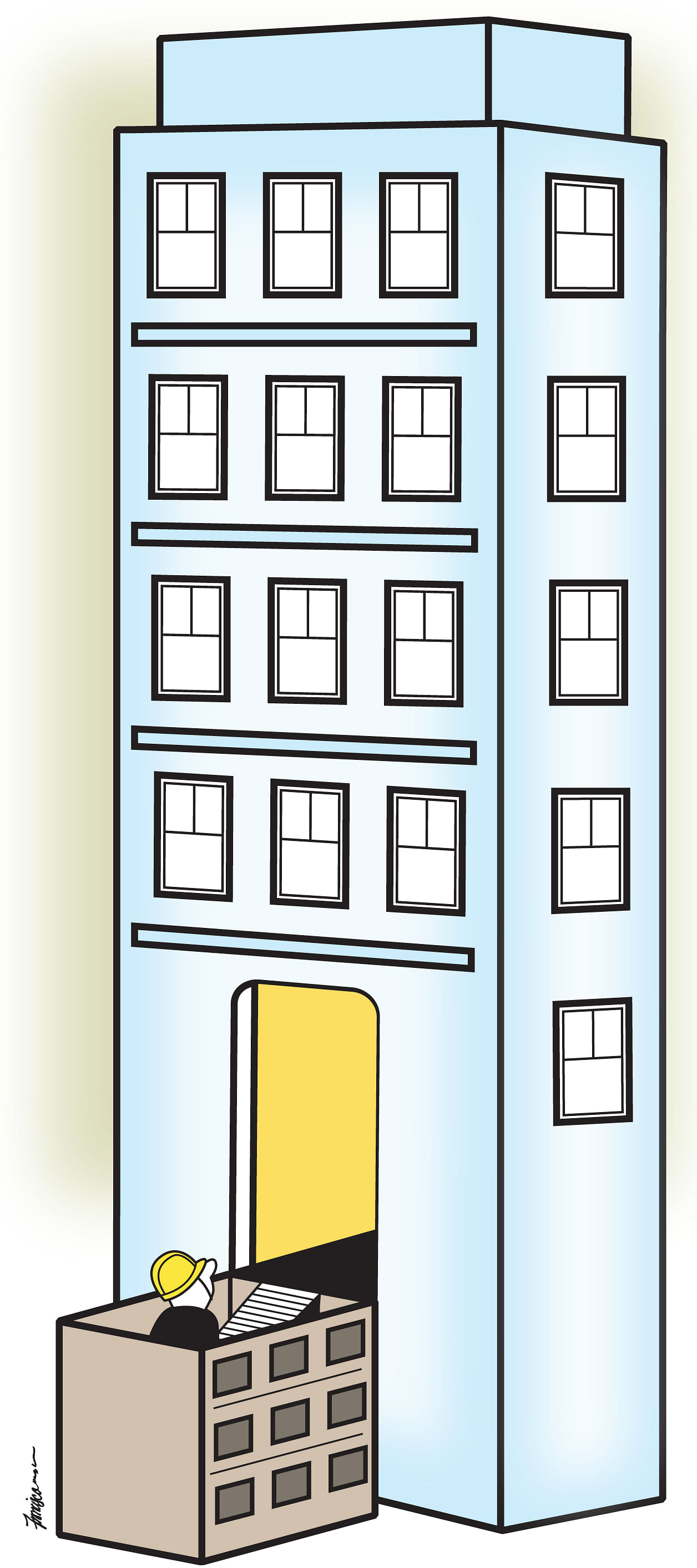

In the meantime, it is not ill-timed to also relook the existing situation, in which tens of thousands of migrant workers doing low-wage manual work are housed in mega dormitories. This is an issue, if not the bigger issue, that Covid-19 has shown Singapore needs to address to avoid facing a similar difficulty in the future.

RISE OF MEGA DORMS

The policy of housing foreign workers in purpose-built dormitories has its roots in the 1990s, when the Government allocated land for companies to build self-contained dormitories with recreational facilities for their workers.

In 2006, a government committee's recommendation led to the ramping up of construction of more such lodgings.

The move culminated in the Foreign Employee Dormitories Act that Parliament passed in January 2015 and which took effect on Jan 1, 2016. The Act was hailed then as a major milestone as it set minimum standards on the living conditions for migrant workers and a licensing framework to regulate operators of dormitories with 1,000 or more beds.

When it was debated in Parliament, then Manpower Minister Tan Chuan-Jin said: "The Government's longer-term view is that the accommodation needs of work permit holders are best met in such dormitories, where there are self-contained living, social and recreational facilities."

The drafting and implementation of the law coincided with a two-year period, from 2014 to 2016, during which 100,000 beds were added, with the rise of mega dormitories.

The biggest in 2014 was the 16,800-bed Tuas View Dormitory.

I was this newspaper's manpower correspondent in the boom years when many dormitories were built.

I visited Tuas View and was impressed by its amenities, including a cinema and a cricket field.

While I was taken aback by the density of the living spaces, I accepted it as an improvement from the squalid shophouses and walk-up apartments in Geylang that had housed the workers.

Two years later, Tuas View Dormitory was eclipsed by the 25,000-bed Sungei Tengah Lodge, which remains Singapore's largest.

THE LITTLE INDIA RIOT EFFECT

The building of dormitories was accelerated by the Little India riot of Dec 8, 2013.

Although the Committee of Inquiry found that foreign workers' employment and living conditions were not the causes of the riot, it suggested that their housing be improved.

The recommendation reinforced the Government's dormitory policy.

The dormitory business is profitable because of economies of scale and a captive clientele.

At the ongoing monthly rate of $220 to $280 for a bed, a 25,000-bed facility rakes in between $5.5 million and $7 million in revenue each month.

Among the players are big names such as a Keppel unit and Singapore Exchange-listed companies Centurion Corp, Wee Hur Holdings and Lian Beng Group. For the 2019 financial year, the net profits of Centurion, Wee Hur and Lian Beng from their dormitory and other businesses were $103.8 million, $34.9 million and $32.9 million, respectively.

Before the coronavirus outbreak, the foreign workers' housing sector seemed to have reached a steady state. About 323,000 workers were living in dormitories, including 43 purpose-built communal townships and other smaller dormitories.

Meanwhile, in June last year, MOM released a report card in which 86.3 per cent of 2,500 work permit holders polled by an independent research firm said they were satisfied working here. The top five reasons they cited included good living conditions.

Then Covid-19 struck.

THE COVID-19 SCOURGE

The first work permit holder with no history of travel to China to be infected with the coronavirus was Case 42, a 39-year-old man from Bangladesh, who is recovering after being in intensive care for two months.

The Ministry of Health announcement on this case on Feb 9 included two worrying details: "Prior to hospital admission, he had visited Mustafa Centre, and stayed at The Leo dormitory."

Both turned out later to be hot spots. By early last month, the coronavirus had spread rapidly to Mustafa Centre (more than 80 confirmed cases) and foreign worker dormitories, even though the cases were officially unlinked to Case 42.

As of yesterday, about 23,000 foreign workers living in dorms were infected with Covid-19, or about 90 per cent of Singapore's cases. The high-density housing of the mini-townships became petri dishes that fuelled the spread of the virus.

Migrant workers group Transient Workers Count Too had warned about the Covid-19 breaking out in dormitories in a letter published in The Straits Times on March 23.

A week later, the first dorm cluster emerged at S11 Dormitory @ Punggol on March 30. The Government responded by isolating dormitories and putting residents on 14-day quarantine in their rooms.

The Singapore Armed Forces moved in to provide medical care, while healthy workers in essential services were moved out to shield them from the virus.

Reports in the media and online soon emerged of workers living in crowded and unsanitary conditions at the S11 Dormitory @ Punggol. Workers reportedly said their rooms were infested with cockroaches and the toilets overflowed.

Their poor living conditions came under the spotlight.

But to Mrs Teo's credit, she promised that her ministry would look into raising the standards of dormitories after the circuit breaker period.

"You have my word," she said on Facebook on April 6.

On April 7, she announced an Inter-Agency Task Force to look after the well-being of foreign workers living in dormitories and support dorm operators during the circuit breaker period. It has since deployed more than 170 teams to cover purpose-built dormitories as well as other housing sites. A range of medical support is also provided to the workers.

WAYS TO IMPROVE STANDARDS

Going forward, there are at least five ways the Government can improve the living conditions of migrant workers.

One, reduce the density.

The Urban Redevelopment Authority sets the minimum living space for each worker at 4.5 sq m.

This is like packing 13 workers into a 60 sq m three-room Housing Board flat, or 20 workers into a 100 sq m five-room flat.

The minimum space has to at least double to make conditions more acceptable.

Singapore exceeds the International Labour Organisation's (ILO) housing guideline of 3.6 sq m per worker, but it has only one toilet, one wash basin and one shower for every 15 workers when the ILO recommends the same number for every six workers.

Reducing density and adding more toilets will improve the well-being of the workers directly.

Two, improve medical facilities.

Dorm operators are required to have isolation rooms or a sick bay: one sick bay bed for every 1,000 beds. Currently, nearly 7 per cent of dorm residents are infected by Covid-19. Although it may be excessive to provide a 70-bed sick bay for every 1,000 residents for an imponderable such as the Covid-19 pandemic, it is plain that one bed is inadequate.

Three, monitor dorm operators closely to ensure minimum standards are met.

For example, dormitories are supposed to have quarantine plans. But one operator's "plan" was to forcibly lock workers in a room after their roommate fell ill last month.

The police are investigating and the operator received a stern warning from MOM.

MOM has about 100 dormitory inspectors working under the supervision of the Commissioner for Foreign Employee Dormitories and they conducted 1,200 inspections and 3,000 investigations last year. About half of the 43 purpose-built dormitories have breached licence conditions each year, Mrs Teo said in Parliament on May 4.

Greater transparency, similar to an annual report card published by the Commissioner for Workplace Safety and Health, can enhance the way these lodgings are run.

Four, rethink the operator mix in the dormitory sector.

Mrs Teo did not mince her words when she said that each time her ministry tried to raise dormitory standards, "employers yelp" over higher costs.

One way to keep costs low could be to have operators run dormitories not for shareholders' profit but as social enterprises.

The National Trades Union Congress is well positioned to do this. It has the financial resources, experience in property development and management, and the backing of the Government and employers. And as a labour movement, it will have its dormitory put workers, not profits, first. An NTUC-run dormitory could set a benchmark for the rest to follow, as it has done in the supermarket, childcare and eldercare sectors.

Five, it is wasteful to tear down mega dormitories, but the capacity of current ones can be reduced while future dormitories should be smaller.

A possible model to follow is Singapore's army barracks.

Like dormitories, army barracks also have double-decker beds in common rooms, shared facilities such as dining halls, toilets, showers and recreation spaces, but we do not hear of complaints of overcrowding.

If the space and density are adequate for national servicemen, they are good enough for workers.

LOOKING BEYOND THE VIRUS OUTBREAK

Dormitory operators and employers, even some Singaporeans, may not look favourably on these changes.

Fewer beds to rent out means lower revenue and profit, and this would prompt operators to raise rents.

This, in turn, would push up costs for employers in housing these workers, and it would cascade down into higher costs for the people. After all, employers have to pay the monthly foreign worker levy, which ranges from $250 to $950 for each worker.

In short, are Singaporeans willing, as a society, to pay more in such areas as construction and cleaning to improve the lot of these workers?

On April 21, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in his live address to the nation: "To our migrant workers, let me emphasise again, we will care for you like we care for Singaporeans."

Let's set our minds on extending the care and concern for them to beyond the Covid-19 pandemic.

It's never too early to do it.

Editor's note: After the commentary was published, Centurion Corp added that its FY 2019 profits of $103.8 million included a one-time fair valuation gain of $66.3 million of its assets, and a more representative figure of its profit from its core business operations of worker accommodation and overseas student accommodation is $38.2 million.