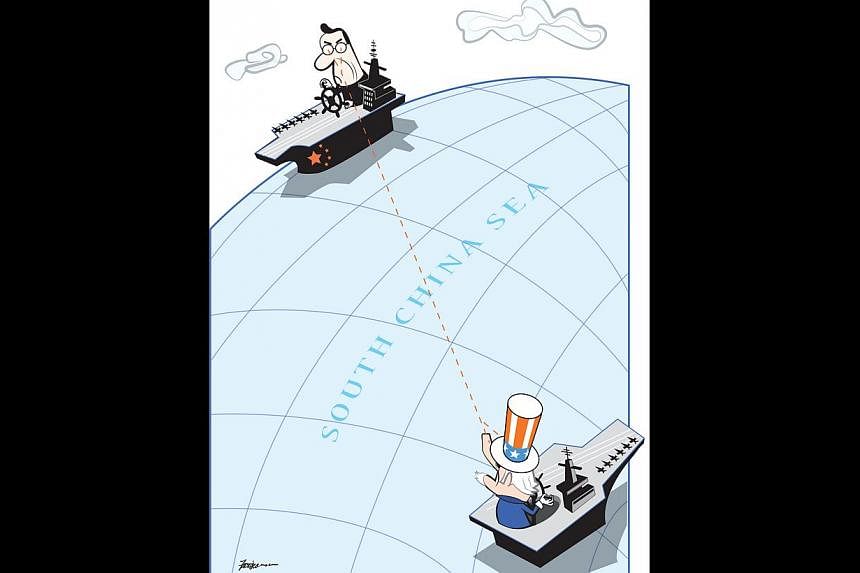

LAST week in the South China Sea, a US Navy P8 maritime patrol aircraft very deliberately flew into airspace around one of the disputed islands claimed by China. It did so to demonstrate America's displeasure at China's development of some of the islands into bases to support military operations. CNN journalists were aboard the aircraft just to make sure the world would see America openly defying China's moves to reinforce its claims to the islands.

This marks a new and more risky phase in the strategic rivalry between America and China which has been brewing for some time now. It seems that people in Washington have decided that the time has come to draw a red line around China's growing power, and that the place to do it is in the South China Sea.

But as President Barack Obama discovered in Syria not long ago, red lines can backfire badly. His administration may find that drawing them in the South China Sea proves more difficult and dangerous than it imagines, and there is a real risk that the whole idea will blow up in Washington's face.

This has nothing to do with the actual territorial disputes themselves, about which America takes no view. Nor, despite Washington's claims, is it really about freedom of navigation in a vital trade route, because there is no suggestion that commercial shipping is at risk. Instead, it is about something even bigger - about who leads in Asia.

Beyond pressing its claims to the islands themselves, China is using its maritime capabilities more assertively in the region's territorial disputes to demonstrate its growing power at sea where America has, until now, always been strongest.

Now America's new approach is to match China's greater assertiveness with a more assertive use of force of its own. But what will this really achieve? The thinking in Washington seems to focus on two linked ideas. One is that by more overtly "standing up" to China, the US will encourage other regional countries to do the same. If so, the argument goes, China will find itself forced to pay a diplomatic price for its assertive behaviour, which will make it think twice before continuing.

The other idea is that a firm show of US resolve will deter China from further challenges to US maritime supremacy and leadership in Asia by reminding China of America's military power and reach in the Western Pacific. The idea here is that the last thing China wants is a war with America, so it will be sure to back off once it is reminded of US power and resolve.

But both these judgments may be based on false assumptions. The idea that a more assertive US posture will encourage others to stand up to China assumes that regional countries are being held back from making a more robust response to China's growing power and ambitions only because the US has not provided the leadership they need to do so.

But the reality is much more complex. All of China's Asian neighbours - even Australia - have an immense stake in maintaining good relations with China. Many of them are certainly uncomfortable about how China will use its power, but they are also very reluctant to take steps which might damage a relationship that is vital to every country's future prosperity. A more assertive US policy is unlikely to persuade them to shift the balance, which each of them has to strike, in managing their relations with China, because that is determined by their strong sense of how important China is to their future.

Likewise, the idea that a more assertive US response to Beijing's actions in the South China Sea will deter China from persevering with them reflects a serious confusion about the concept of deterrence and the balance of advantage between the US and China today.

Deterrence was, of course, a central factor in the Cold War. Even minor clashes between the US and then Soviet Union were avoided because both had not just the military capacity but also, critically, the will to fight a full-scale nuclear war to preserve the status quo between them.

Both sides understood that the other saw the issues between them as so central to their national survival that they would accept the appalling costs of major war rather than surrender them. That meant that leaders on both sides knew that even a small clash would present them with the choice between a humiliating backdown and a terrifying escalation towards a nuclear exchange.

Since the end of the Cold War, however, many people in Washington seem to have forgotten the essential role that evident will plays in deterrence. They now assume that simply having the capability to fight a major war will deter adversaries like China from taking steps that Washington does not like.

But that is not so. America's armed strength will deter China from pursuing its assertive policies in the South China Sea only if Beijing is convinced that America has the will to actually go to war with China.

Back in the 1990s, it was clear that America did indeed have that will. That was because the costs and risks of a US-China conflict to America were relatively low, both militarily and economically. But over the past few years, as China's military capabilities and economic weight have grown, the costs to America have grown very sharply.

America's prosperity would now be as devastated as China's if a conflict disrupted economic flows between them. And America today would stand to lose major military assets like aircraft carriers which were once considered invulnerable, and the risks of escalation up to and across the nuclear threshold are much higher.

Indeed, as the costs and risks to each side have equalised, China might today be better placed to deter the US than vice versa. It seems likely that China would be more willing than the US to allow a crisis in the South China Sea to escalate into a war. If so, America's assumption that China can be deterred from staking its claims to regional leadership in the South China Sea by minor infringements of its claimed air and sea space is a dangerous and outdated delusion.

This leaves a big question: What can America and its Asian friends and allies do in response to China's power? The first step to an answer is to recognise that the choice is not between outright defiance and abject surrender. There are more options to choose from. The task of America and its friends is to explore those options.

The writer is professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University in Canberra.