In The Necessary Stage's classic play Those Who Can't, Teach, which casts the spotlight on life in a typical secondary school in Singapore, there is a scene in which a student, Teck Liang, contemptuously lashes out against his working-class father, a fishmonger.

He scornfully questions why his father must work in a market, and does not wear a tie and jacket to work in an office. Unlike a wealthier classmate, Raymond, Teck Liang's father cannot afford to buy him Nike shoes, nor does he own a car or condominium unit. These differences fuel Teck Liang's sense of shame and self-hatred.

It has been more than 20 years since the play was first staged, but its stark illustration of how the classroom often serves as the setting in which children's eyes are opened to the realities of socio-economic difference remains relevant.

A recent move by at least six primary schools here to shield students from the effects of inequality by issuing guidelines against extravagant birthday celebrations - involving sweet treats and goodie bags - has sparked debate.

While schools explained that this would deter comparisons between the haves and have-nots and avoid situations where parents feel pressured to spend on their children whether or not they could afford it, some have dismissed the move as excessive mollycoddling.

After all, why deprive children of a chance to commemorate an event that only rolls around once a year? Others argue that since the practice of birthday celebrations has become common at the pre-school level, there is no reason to discourage them in primary schools.

A TIME AND PLACE FOR EVERYTHING

Just to be clear, there is no national ban on birthday parties in schools. Those primary schools that have guidelines to discourage extravagance have implemented the new rules with a light touch.

Parents, for example, were reminded that they could mark such occasions at home with friends and family. Other schools, like Riverside Primary in Woodlands, emphasised that birthdays can be celebrated meaningfully with a song in class, without the trappings of materialism.

As public institutions, schools play an important role in communicating and inculcating values through their practices.

Take the wearing of the school uniform, a practice that has been in place since before independence. By enforcing a standard dress code, schools send a symbolic message that students are all equal in the school environment, and reduce comparisons between students based on the brands and provenances of their clothes.

While more schools have been relaxing guidelines in recent years, with quite a few now allowing students to wear branded sports shoes provided they conform to a particular colour scheme, they have also been careful to communicate that such concessions are a privilege.

AGE AND SOCIAL STATUS

At a young age, markers of income disparity - whether in terms of appearance, material possessions or even something as innocuous as whether one has the ability to hand out birthday party favours - are "experienced keenly in the school, the centre of students' social and educational lives", noted Associate Professor Irene Ng from the National University of Singapore's (NUS) Department of Social Work.

It may also snowball into something more distressing for students, according to NUS sociologist Tan Ern Ser, who said that problems of stigmatisation and bullying of students who are less well-off may exist. These may not always be picked up because they "may be misconceived as a behavioural and disciplinary matter", rather than a matter of social difference, such as bullying behaviours displayed by cliques formed on the basis of similar socio-economic background.

Previous interviews conducted by The Straits Times demonstrate how students are affected by such differences.

Those from less well-off families in independent schools recounted how buying branded goods and treating people to meals or events become prerequisites for "being cool" in school. One even shared an anecdote about a student who lived in public housing but who lied and said she lived in a condominium and also stole money to "treat" others so as to keep up appearances.

Some experts are of the view that children have not developed the maturity or vocabulary to discuss the meaning and impact of social differences, and yet are able to recognise such differences.

Singapore Children's Society chief executive Alfred Tan noted that guidelines against displays of material wealth in school are a first step in reducing comparison and pressure. But unlike Singapore's early days, when enforced uniformity in schools had more concrete impact beyond merely establishing a veneer of equality, it is now difficult to shield children from such comparisons in this age of social media.

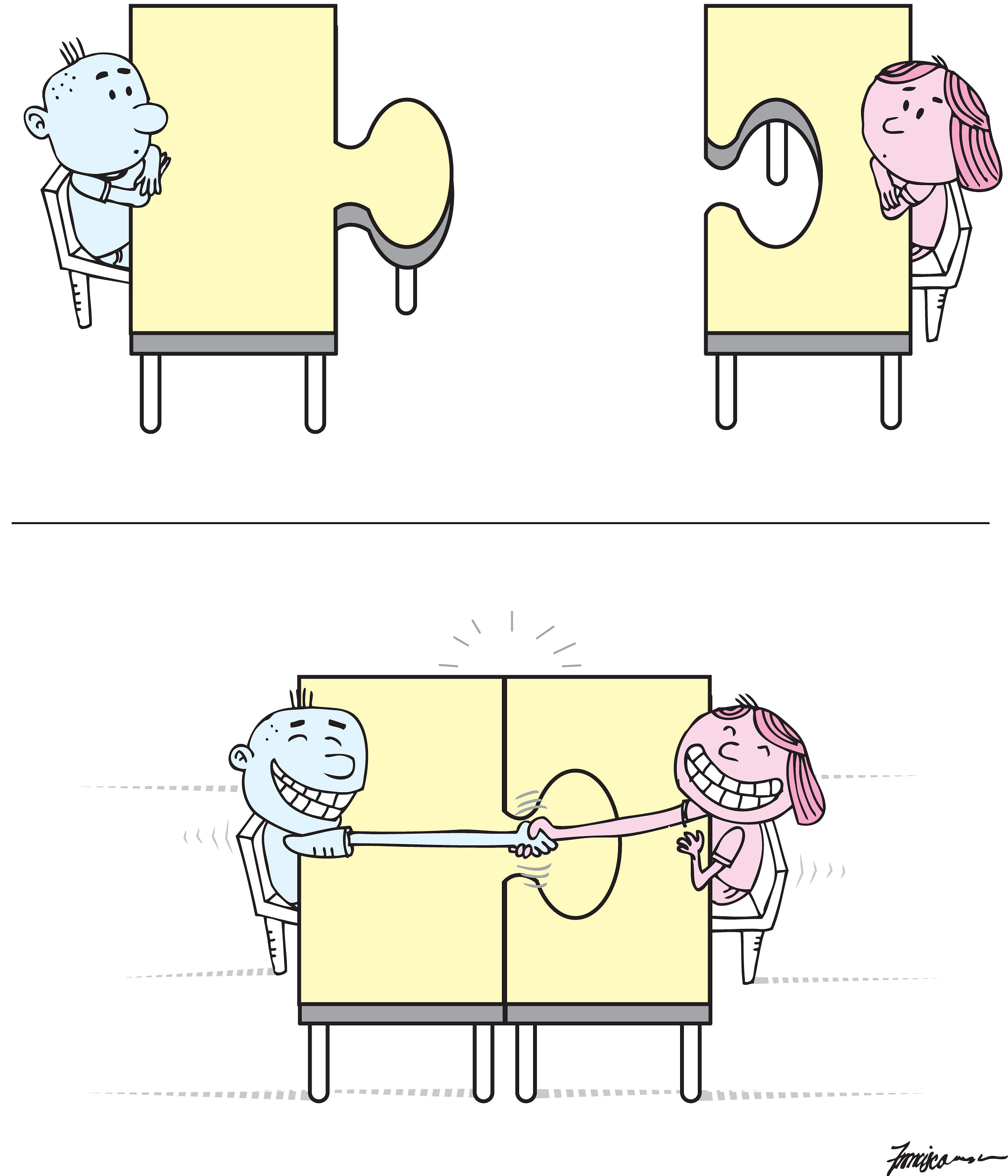

He suggested that schools seize instances where such comparisons arise as an opportunity to teach children about social differences and inculcate values. "We don't want to stigmatise one group or patronise another (by introducing too many rules). At the end of the day, I believe (open discussion) will benefit everybody."

Such discussion, said Prof Tan, should not harp on socio-economic difference, "but point to inclusiveness and equality of opportunity".

Pasir-Ris Punggol GRC MP Zainal Sapari, who sits on the Government Parliamentary Committee for Education, concedes that it can be difficult to strike a balance between introducing such guidelines in schools and maintaining flexibility.

As a student from a low-income family, he had once looked upon his schoolmates' branded shoes with envy when the school allowed them to be worn for weekend events. When Mr Zainal later became a principal at Mayflower Primary School, a post he held from 2003 to 2009, he disallowed his pupils from holding costly birthday celebrations, and from bringing mobile phones to school, to discourage comparisons.

"But such rules will change over time. Each school has a different mix of students from various socio-economic backgrounds, so it depends on the comfort level of the school community," said Mr Zainal, who does not believe it would be productive for the Ministry of Education (MOE) to issue a top-down directive on such matters.

After all, such guidelines "may not be the best way to teach (students) that there is income disparity in society," he said. At the end of the day, what schools have to do is create a safe environment for students to learn, where they are free from unwanted pressures, he added.

Mr Tan of the Singapore Children's Society suggested that MOE strengthen its collaboration with parents, and guide them on how to teach their children to navigate and overcome socio-economic differences.

If children get their values right in terms of looking beyond face-value attributes such as social status or wealth at an early age, it will be more beneficial in the long term, he said.

If the subject of social disparity does surface, discussing it, even among children, need not be a daunting task. For example, the use of tools like children's books or role-playing can help ease children into sensitive discussions and reflection about such differences and how groups that are marginalised can be included.

With Values in Action now part and parcel of most primary school programmes, taking extra time out to encourage deeper reflection on issues like inclusion will equip pupils with skills for life as they progress further in their education journey, and become exposed to people from backgrounds that are even more diverse.