This week's day of the long knives in Malaysia which saw the Deputy Prime Minister, another minister and the Attorney-General leading the list of notables who lost their jobs, has elements of great melodrama.

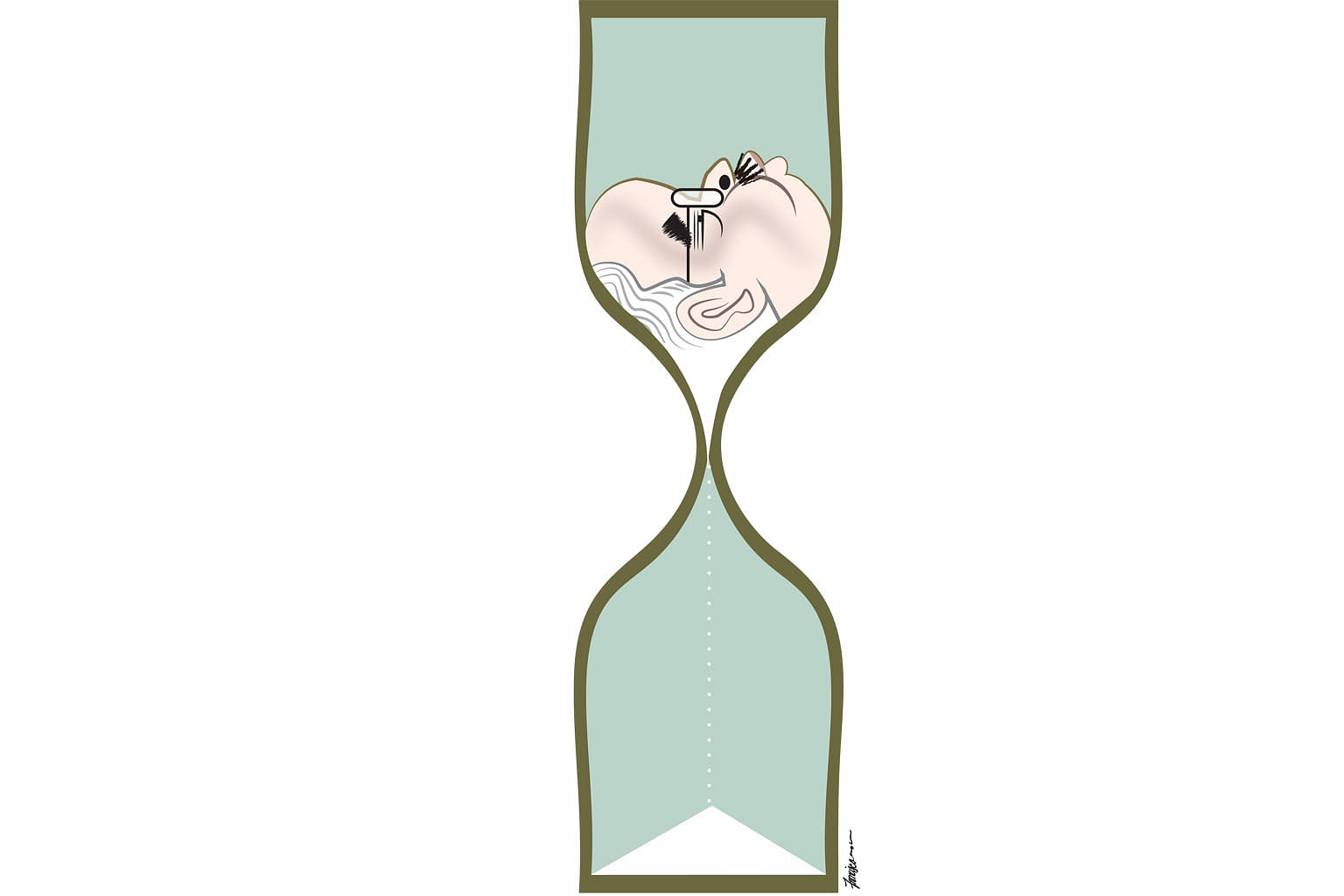

In the middle is the pedigreed Prime Minister Najib Razak, son and nephew of the nation's second and third premiers, a golf-playing, urbane presence with ties to world leaders. Until recently, and perhaps still, he had the goodwill of the dominant Malay population that firmed his grasp of the United Malays National Organisation (Umno), the party that heads the ruling coalition.

Despite the cynicism bred by years of Umno incumbency and its attendant ills, Malaysians, especially in the rural areas, had a positive image of their leader. His public positions, including the 1Malaysia concept, suggested an inclusive agenda that comforted the nation's progressive-minded youth. Minorities, including the substantial and economically powerful Chinese, warmed

towards a man who beat drums at Chinese New Year festivities. Demolitions at Hindu temples ceased as he reached out to the Indian community and showed up at their festivals.

For all his efforts, though, his Barisan Nasional (BN) did not win the popular vote in the key 2013 polls. The Umno-led BN prevailed only because rural constituencies outnumber the urban ones in the national Parliament, a legacy from the days when most Malaysians lived in the countryside.

Urban Malaysians, now three-fourths of the population and able to see the ways of their politicians from closer range, had expressed themselves strongly against the government. Chinese, particularly, voted opposition in large numbers, deserting the BN's partner, the Malaysian Chinese Association. Frustrated by the minority response to his efforts, Datuk Seri Najib complained of a "Chinese tsunami".

When you cut away from your partners and plough your own furrow, it's wise to guard the flanks. Mr Najib had his share of enemies, including, increasingly, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia's longest-serving prime minister.

Aside from a desire to see his son Mukhriz's political career advance faster, Dr Mahathir also had ideas on governance that did not square with Mr Najib's. There were other Mahathir peeves, one of which was Mr Najib's attitude to Umno Youth chief Khairy Jamaluddin, son-in-law to the man who succeeded Dr Mahathir in office, Tun Abdullah Badawi. The tall, charismatic Mr Khairy is something of a bugbear for Dr Mahathir. This is why Mr Najib did not take him into Cabinet in his first term, although previous Umno Youth chiefs routinely got ministerial jobs. Personally well-disposed to Mr Khairy, he waited until after the 2013 election to give him a Cabinet berth.

Perhaps Mr Najib was careless about his finances. Malaysia's politics, as in many Asian democracies, is often perceived as being oiled by abundant funds to sweeten the ground. Elections, particularly, are an expensive affair. As party chief, every candidate looks to him for endorsement and financial support.

A widening controversy over the alleged multimillion-dollar deposits in his personal account, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, is under investigation by the Malaysian government and a parliamentary committee. Mr Najib's position is that he received no money for "personal gain".

The pity is that all this is weighing heavily on Malaysia's economy, leading to a plunge in the currency and the stock market. Tan Sri Dr Zeti Akhtar Aziz, the widely respected central bank governor, is not wrong when she says Malaysia's economic fundamentals are sound. The economy is forecast to grow between 4.5 per cent and 5.5 per cent this year. The ringgit's sharp decline is really not so much on account of fundamentals as the political uncertainty in Kuala Lumpur.

It is noteworthy that amid an emerging markets slump, Fitch recently maintained its investment-grade rating after signalling a downgrade in March. Moody's has retained the A-minus rating it bestowed in 2013 and has a positive outlook, it said on June 30.

But politics is about seizing the moment and his detractors think they have theirs. By not offering a convincing explanation for the money trail, or an outright denial of the existence of vast funds, Mr Najib has left himself vulnerable. Not surprisingly, he behaves as though there are enemies lurking in the shadows.

Perhaps he is not off the mark.

Treachery in Asia often comes mixed with food and sherbets.

Seven months ago, Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa shared a convivial meal of hoppers - the bowl-shaped pancakes eaten with stew and chutney - with his trusted Cabinet mate Maithripala Sirisena. The next morning, Mr Sirisena announced he was cutting away from his master and contesting against him. In politics, it is not uncommon for the stilettos to be wrapped in smiles.

Attending the various breaking fast gatherings of the past month, the beleaguered Mr Najib may well have pondered over how many of the benign smiles and obsequious greetings were sincere. Certainly, there was no shortage of speculation in Kuala Lumpur.

Regardless of whether or not Mr Najib rides out the current storm, there can be no question that his government has been dealt a bruising blow. A leader's response to controversy can create fresh problems.

It is worth remembering that in United States President Richard Nixon's fall over the Watergate scandal, his bid to cover up wrongdoing became more controversial than the crime.

Mr Nixon left office, handing power to his vice-president, who promptly issued a presidential pardon to his predecessor.

Perhaps Mr Najib can live out the three-year remainder of his term in the manner of a Manmohan Singh in India, his nation's body politic weakened by the wounds of scandal. He can take comfort, for now, that there are no mass demonstrations on the streets of Kuala Lumpur as witnessed in the last days of the Marcos and Suharto regimes in neighbouring Philippines and Indonesia. Perhaps he can even continue to argue, as Dr Singh did in India, that he did not receive funds for "personal gain".

But Malaysia is not India, and Umno isn't the Congress Party, increasingly accustomed to sitting in the Opposition as much as the Treasury benches it once dominated.

Fear of losing power dominates Umno calculations, including the burying of old animosities and the forging of new alliances. Some commentators this week maintained that Mr Najib's actions in firing Deputy Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin and some others have gone down well with the ground, because "Malays like strong rulers".

But the more telltale sign is Umno's decision to postpone the Supreme Council meeting scheduled to have been held today. It suggests that Mr Najib, despite his vast powers as Prime Minister, Finance Minister and party leader, is not entirely sure of what might happen in those councils.

Then again, uncertainty is inherent in politics.