Thirteenth out of 63. That's how Singapore ranks in the latest World Talent Report, released recently by Swiss business school IMD. Not a bad showing, you might say, which is true. But there is good news and bad news.

The good news is that Singapore scores high (second) on its "readiness" for the new economy, which includes the quality of its education system, managerial competence and the international experience of its managers. Were it not for its sluggish labour force growth (ranked 37th), it might have made the top spot for readiness.

Singapore ranks reasonably high (17th) on its "appeal", which encompasses its ability to attract talent, the quality of life and remuneration levels - although the ranking was dragged down by the high cost of living (ranked 59th).

The bad news is that it scores abysmally low (41st)on "investment and development", which includes public expenditure on education (ranked 59th) and female labour force participation (37th). It also scores low on its effective personal income tax rate (ranked 45th) and so-so on employee training by companies (25th).

In some of the areas where Singapore is lowly ranked - cost of living and personal income tax rates - not much can be done in the short term. Cost structures are impossible to change quickly, and the tax system faces strain from increased social spending and an ageing population. But on some of the others - particularly public expenditure on education and employee training - there is scope for corrective action.

Although Singapore's public spending on education is the second-largest item in the Budget after defence, it is not generous enough compared with other advanced economies, particularly at the post-secondary level. We spend about 3 per cent of gross domestic product on education. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development average is close to 5 per cent and in some countries like Denmark, Sweden and Belgium, it ranges between 6.5 and 7 per cent.

The difference shows up in comparative education profiles. While more than 52 per cent of Singaporeans aged 25 and above now have post-secondary education, the corresponding figure for countries of the European Union is close to 80 per cent. If we are to compete effectively in the digital age, we have some catching up to do. This will take years, but one way to speed up the process would be to make tertiary education free for all Singaporeans, at least up to a first degree.

Of particular importance is raising digital capabilities. Another recent survey released earlier this month by the Brookings Institution on trends in the United States labour market had some startling findings, many of which would also be valid here.

First, jobs that need high digital skills jumped from 5 per cent in 2002 to 23 per cent last year; jobs needing medium digital skills rose from 40 per cent to 48 per cent; and jobs needing low skills dropped from 56 per cent to 30 per cent.

Second, there are huge wage differences between workers depending on their digital skill levels. The mean wage for high-skilled workers last year was US$72,000 (S$96,850), compared with US$30,000 for low-skilled workers. In other words, digital literacy is now a key determinant of income inequality between workers.

Third, digital skills are a protection against automation. The percentage of tasks susceptible to automation in low-digital occupations is nearly 60 per cent, compared with just 30 per cent of tasks performed in high-digital occupations. So if we are concerned about the impact of automation on jobs - which we should be - raising the level of digital skills must be a priority. The Brookings study recommends that even those workers without college degrees need to have some knowledge of basic workplace software like Microsoft Office.

But the study adds that protection against automation can also be gained by developing skills that computers and artificial intelligence systems are not good at, such as adaptability, creativity, interpersonal and social skills like caring, coaching and nurturing. These are not sufficiently emphasised in formal education systems, even those which, like Singapore's, are highly rated on other metrics, such as academic standards and the emphasis on science subjects; the traditional measurement metrics are themselves becoming obsolete.

When it comes to developing skills and retraining, one of the problems in Singapore is that while government agencies are doing a lot, employers are not doing enough. A survey by human resource company Hays earlier this year revealed that only 16 per cent of respondents from Singapore depend on their employers to provide training and development. At a time when thousands of jobs are being redefined or becoming redundant and the demand for new skills is rising, this must change.

An example of a company that is proactive in reskilling its staff is US telecom giant AT&T. It's an especially interesting example, because it is the archetypal "legacy company" with huge assets in cables and other hardware which performed functions which are now performed by the Internet and the cloud.

In 2013, AT&T identified a problem that should be familiar to other legacy companies: About 40 per cent of its 240,000 staff were doing jobs that in 10 years would be obsolete.

Instead of waiting to retrench workers and then rehire people with the right skills, it chose to launch a massive retraining programme for its existing staff called Workforce 2020. It spent US$250 million on employee education and professional development and more than US$30 million a year on tuition assistance. It developed a self-service platform that enabled workers to assess their own skills, identify gaps in their competencies and correct them. By last year, the results began to show. Retrained staff were able to fill about half of all technology jobs and the product development cycle shortened.

Not many companies have the resources to do what AT&T did. But the core of its idea is to create a culture of perpetual learning. Companies can do this in different ways - for example, by systematically identifying gaps in competencies, subsidising online courses, recognising certifications like "nano-degrees" (degrees in particular tasks, like Web development) and allowing more paid leave for study and retraining.

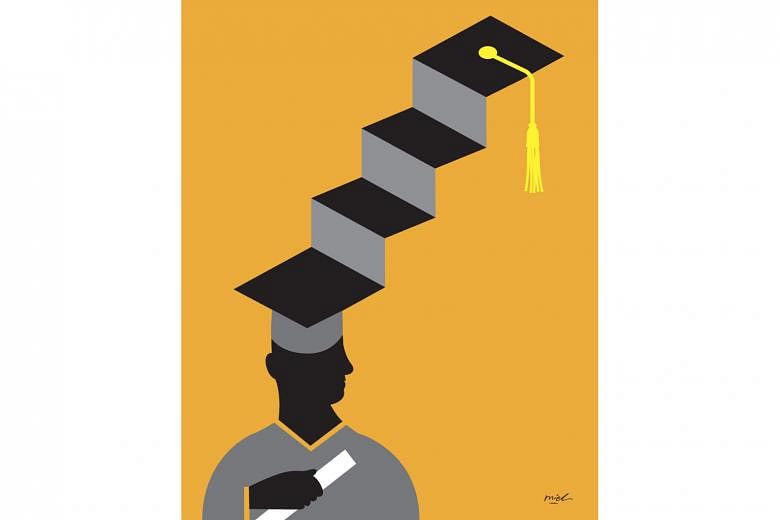

But in the age of accelerating job obsolescence, perpetual learning has to go beyond the corporate world. Society must embrace the idea that the days of front-loaded education - where we study till our early 20s and then we're done - are over. More 30-somethings and above need to enrol in courses and even in universities and polytechnics. Fresh graduates need to know that graduation day is not the end of their education, only the end of the beginning.

And we all must develop the one big skill that nobody taught us before: the passion to keep learning.