LONDON • Few world politicians are as admired as France's President Emmanuel Macron is at the moment.

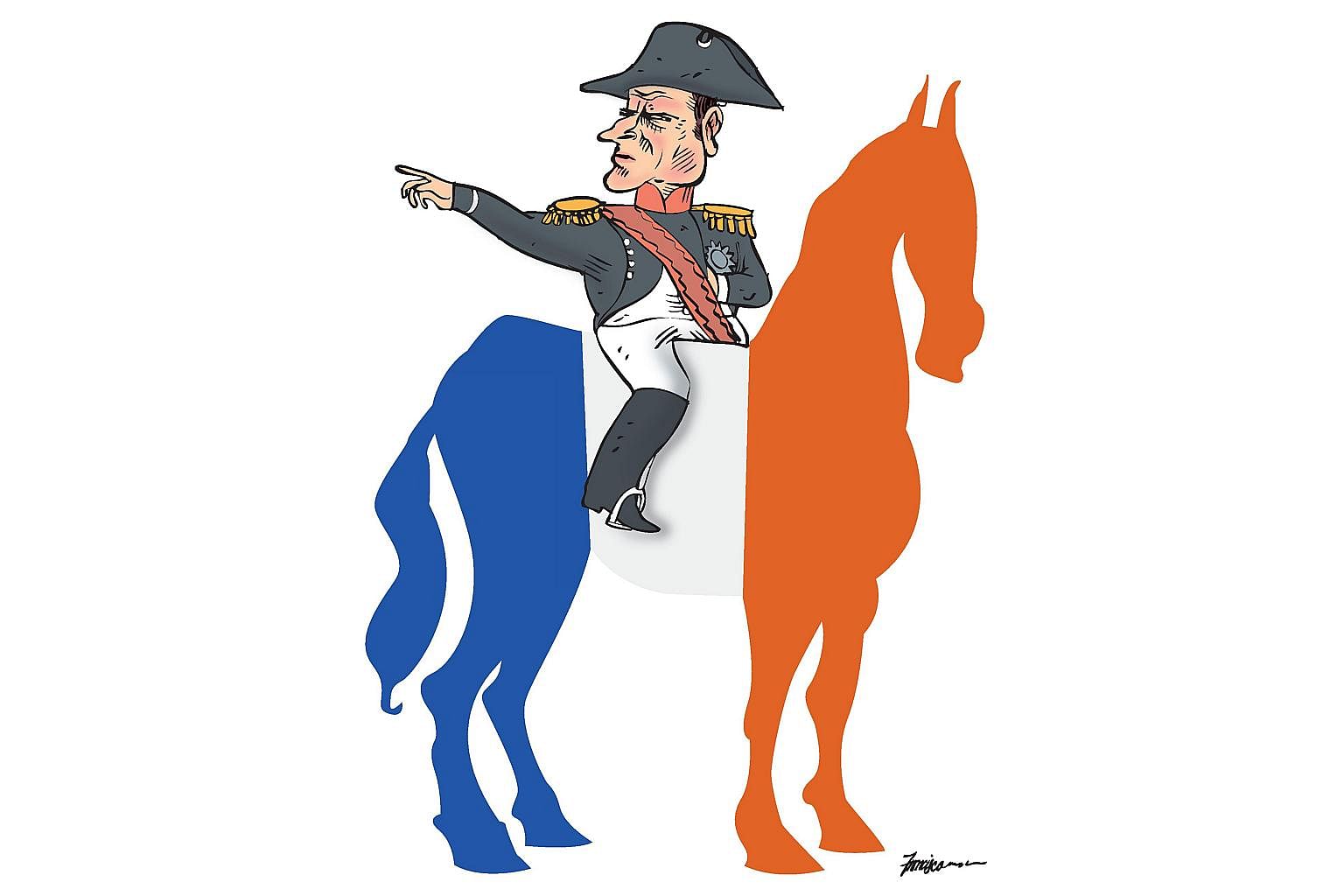

The 39-year-old - France's youngest leader since Napoleon - is hailed as Europe's saviour, someone who not only managed to defeat both far-left and far-right opponents at home but also in the process slayed the demons of populism and racism stalking the European continent. His bold programme of economic reforms at home is described as a model for others to follow.

His bold global leadership is equally admired. Only last week, Mr Macron hosted the US President and the German Chancellor, and both looked as though they hoped some of the shine of France's head of state would rub onto them as well. Earnest looks, sharply- tailored suits, the ability to say the right thing and a knack for flirtatious winks to media photographers, Emmanuel Macron is the poster boy of a modern leader, the man who has others eating out of his palm.

But just as "Macronmania" reaches new heights, a strong dose of caution is recommended. For the reality is that although President Macron should clearly be counted as one of today's most astute politicians, his phenomenal rise to power is mostly explainable by a mixture of luck and special circumstances, and should not obscure the fact that his style of government still amounts to a monumental gamble which could fail, with grave consequences for all of Europe. Ultimately, few of those who pretend to be walking on water do so for long.

Mr Macron's supporters like to portray him as a revolutionary, a man hell-bent on upending France's establishment by dragging it into the 21st century. But the reality is that he is very much a product of the same establishment he claims to dismantle. Like most of France's leaders, he went through the grandes ecoles, the highly-selective elite educational establishments which operate outside the mainstream university system as sausage manufacturers for France's ruling class.

And like all people in his bracket, he was helped in his career by guanxi, which works in France in an identical way to China: earn someone's trust and friendship, land a little job in the private office of a grandee and, bingo, a ministerial portfolio and effortless fame. Before becoming president, Mr Macron held no elected office and fought for no competitive position; in this respect, the only politician with an identical political path is none other than Mr Donald Trump.

Yet, had it not been for an extraordinary set of circumstances - all of which were beyond his control and none of his doing - Mr Macron would have still failed to become president. He benefited from the fact that the incumbent French head of state was so unpopular that he was persuaded not to stand, that France's left-wing voters were split between two candidates, that the centre-right Gaullists were led by an elderly patrician figure embroiled in a personal financial scandal and, finally, that the leader of France's far-right movement drew enough votes to weaken other candidates but never had any chance of winning.

In short, what ultimately propelled Mr Macron to the Elysee Palace was the sort of political upheaval which happens only once in generations. And even then, just a handful of votes separated him from his nearest rival in the first round of the French presidential elections; had 60,000 ballots out of 36 million votes cast gone the other way, nobody would be speaking about Emmanuel Macron today.

THE BOSS AND PARLIAMENT

Of course, in politics luck counts for a great deal, and nothing succeeds more than success, so nobody can begrudge Mr Macron for being the right man at the right time and in the right spot. Still, it's worth remembering that his actual electoral support is nowhere near as impressive as it currently appears.

And it's also worth recalling that his phenomenal reputation outside France is largely based on lack of knowledge about France's domestic scene. Had a rich kid with an exclusive education become British leader at a young age, most people around the world would put it down to pure favouritism; Mr David Cameron, Britain's premier until last year, was never allowed to forget his similar past. But when Mr Macron rose to power in exactly the same way, almost everyone outside France put it down to his brilliance.

And had a British or, say, Australian leader entertained Mr Trump with a military parade, lavish dinners and lots of hugs, the world's English-speaking, left-leaning media would have been outraged. But when the French President did precisely that last week, none other than Britain's Guardian newspaper hailed Mr Macron as "a genius in diplomacy", a man who "showed elegance and discretion" in handling Mr Trump.

Mr Macron would be well advised not to allow such flattery to go to his head, for it won't last long after the novelty effect wears off.

But it will be the President's domestic policy choices which could come back to haunt him. Mr Macron had the option of using his presidency to forge a new political consensus between the left and the right in France; he could have done this through the simple expedient of capturing the presidency, but not forming his own party.

Instead, he could not resist the temptation of capturing as much power as possible by establishing his own political movement and by ensuring that this won control over Parliament. Yet that was not in order to ensure that his legislation got through; rather, it was to emasculate Parliament altogether.

All his measures since the parliamentary elections last month consist of marginalising lawmakers; Parliament was asked to provide the government with full powers to change labour legislation by decree, and Mr Macron also announced his intention to change the electoral system to one of proportional representation, a move which, if implemented, will ensure that far-right movements will have a bigger presence in the National Assembly, but will also result in the creation of a legislature which is so paralysed as to be irrelevant.

Completing this picture is Mr Macron's penchant to rule as an elected monarch. The first president in modern France not to have had any experience of the military loves nothing better than parades, salutes and marches; "I am your boss," he admonished some of France's top army generals after they had the temerity of complaining before a parliamentary committee that the newly-elected President has gone back on his pledge to invest in the country's defences by cutting France's military budget.

A NEW MONARCHY?

Mr Macron also enjoys entertaining both visiting heads of state and lawmakers in the sumptuous surroundings of Palace of Versailles, the gilded spectacular surroundings built by Louis XIV, France's "Sun King", just outside Paris. Unlike Mr Nicolas Sarkozy, another recent French president, Mr Macron does not wear bling. But he certainly likes to be surrounded by official bling, and plenty of it.

There is a serious meaning to this method, which the French media has already dubbed as the "Jupiterian presidency", after Jupiter, the king of gods in Roman mythology.

Mr Macron has rightly concluded that the French may be republican, but respect only leaders who act as monarchs. So, unlike his immediate predecessor Francois Hollande who famously described himself as "normal" and ended up with abnormally low ratings, Mr Macron is determined to talk to the French from the height of Olympus.

There is also a justification for trying to ram through economic and social reform from above. For, as General Charles de Gaulle, France's wartime leader, memorably put it about half a century ago, "How can you govern a country which has 246 varieties of cheese?"

The French actually have more than 1,000 various cheeses, so Mr Macron's impulse to rule with an iron fist makes some sense.

Still, this approach remains dangerous. For there is no consensus for the reforms which the President proposes to introduce, and no political class invested in its success. If the measures produce the expected outcome and France flourishes, Mr Macron would be hailed as a second General de Gaulle.

But the moment the reforms appear to flounder, he will find himself alone; the downside of personalising power to such an extent is that responsibility ends up with only one person. The god Jupiter can retreat into the clouds; Mr Macron cannot.

All of those who believe in Europe's future should hope for Mr Macron's success, for what happens in France is key to the rest of the continent.

Yet hope is no substitute for reason. And any reasonable analysis of France indicates that Mr Macron is engaged in a dangerous gamble, for very high stakes.