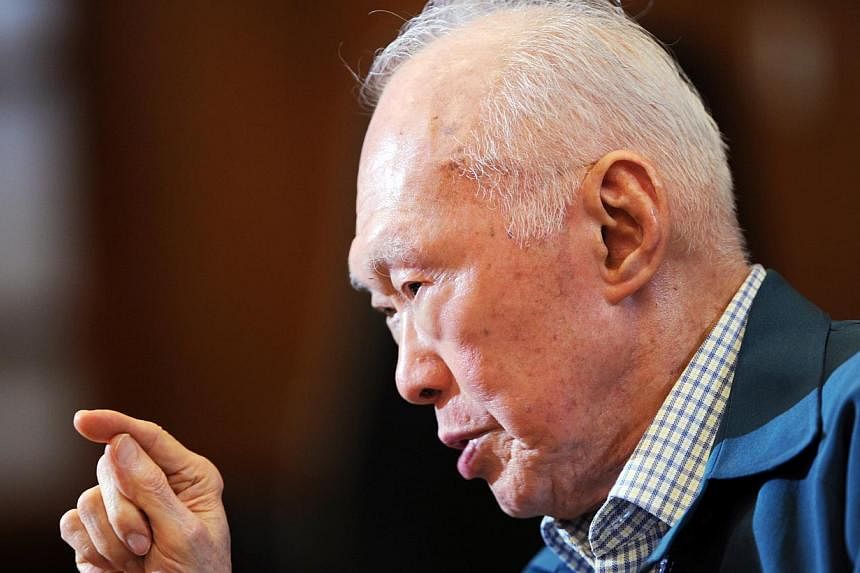

Mr Lee Kuan Yew's most powerful ideas were often counter-intuitive, out of the box, controversial, world changing. Before we get to the quality of his ideas, let us look at the simple and perhaps boring and predictable narrative that has been circulating recently.

In the course of the last two weeks there has been an outpouring of views written by many about the legacy of our founding father [of the Republic of Singapore], ranging from blind idolisation to vulgar derogation. How Singaporeans will remember our founding father depends quite predictably on their hierarchy of needs and how their lives have been directly or indirectly affected by the Lee Kuan Yew regime.

From a near zero economic base in 1965 the man has provided jobs, homes, healthcare, recreational facilities, better education for our children and opportunities to get rich through business and hard work. Those from this camp will accord him with the highest honour.

Those who yearn for greater intellectual and political freedom including those who have been imprisoned or banned from returning to Singapore would cast him as an autocratic demon. The endless debate will not go away soon.

Mr Lee Kuan Yew may have been accused of many things in his life, but not even his worst enemy will accuse him of not living and breathing Singapore and not devoting his whole life to making this country work. His methods may have been questionable but his heart was always in the right place.

Singapore is undoubtedly an economic shining beacon. Whether the soul of the nation has been sufficiently nourished and whether true happiness and contentment achieved is the subject of another discussion.

The domestic accomplishments of Mr Lee Kuan Yew need to be viewed in the right context. That context is set in 1965 from the perspective of Singapore looking at the world, particularly Asia.

He inherited a population which was largely uneducated and not quite properly brought up by any modern standards. Quite a few Singaporeans who moved from squatters to new government subsidised flats regarded urinating in lifts as acceptable practice for instance. Gangsters and secret societies roamed the streets freely.

Arguably, it was necessary for Mr Lee Kuan Yew to wield a big stick to govern Singapore at the time. Plus his Machiavellian action were largely born of fighting for his life and witnessing gross injustice and inhumane practices during colonialism, communism and the Japanese occupation. He has publicly acknowledged that it is better to be feared than loved as a leader, if you cannot be both.

But to better judge the man, we should read his books, study what the deep thinkers of the world said or wrote about him, analyse his speeches and listen carefully to the many interviews he has given. As his grandson puts it, Mr Lee Kuan Yew was a man who spoke with the courage of his convictions and a certainty born of long consideration.

Mr Lee Kuan Yew had the ability to absorb disparate data and synthesise it into a generalisation. This allowed him to create a way of thinking about problems which could integrate the disparate streams of data into a mental model that made sense. To borrow a phrase from New York Times columnist, David Brooks, Mr Lee had that "uncanny ability of capturing amorphous trends with a clarifying label". Mr Lee was someone who recognised that problems could not be solved well when divisible into parts (and solved separately) but needed to be looked at as whole systems.

So in my view, what is the real legacy of Lee Kuan Yew?

To me, it is this powerful albeit controversial idea, born of long and deep consideration, and particularly relevant to emerging Asian states whose people are born of "Asian values", that in return for giving up some freedom, the state would house them, provide good jobs and business opportunities, educate their children and eventually offer the people a standard of living even the west would envy.

China has borrowed this idea and if the economic giant continues to progress in the next 20 years while remaining a one party governing system, Mr Lee Kuan Yew's hypothesis will get wider acceptance, especially in Asia.

And Mr Lee Kuan Yew has figured out that in order for this controversial model to work, whether in Singapore, China or anywhere else in Asia, it is crucial that a fairly transparent legal system be established over time to create a secure and predictable regime for business and economic progress, while more restrictive laws are used to govern political participation and the media.

Mr Lee Kuan Yew would have called this the art of borrowing proven best practices of the west and discarding other deemed bad practices. To a large extent, China has already adopted this idea.

China has long been a country open for business to the west but closed for politics. This duality is of course not cast in black and white but shades of grey. Over time, the space for dissent will enlarge while the core governing idea remains the same. Even western liberal democracy has been modified over time.

So the western world patiently awaits the answers to these questions. Is Singapore a singular state? Will Lee Kuan Yew's Singapore model follow him to his grave? Is the Singapore experiment a stand-alone one based on the city state's unique attributes or does the idea carry universal application, meaning can Mr Lee Kuan Yew's unique and counter-intuitive idea of political governance be copied, modified and even perfected further by other Asian autocratic states as long as they produce honest and brilliant leaders who are also modernisers?

Hence the Lee Kuan Yew paradox, whether by accident or by design, is that he has left behind a model which China, as a rising economic giant, wishes to see continue to perpetuate and flourish.

In other words, China vicariously has a stake in the future success of the current Singapore model. If Singapore breaks and follows the ways of the liberal west the efficacy of the Chinese one party political system may be seriously called into question.

As a born and bred Singaporean, I am proud of the fact that our founding father is one of the best global interlocutors who has ever lived and I am proud of the fact that the future success or failure of our governing model may have a direct impact on the lives of one quarter of the world's population in the years to come. Truly, we live in interesting times.

"I am not given to making sense out of life, or coming up with some grand narrative of it," Mr Lee wrote in 2013. "I have done what I wanted to do to the best of my ability. I am satisfied."

As for me, I may not necessarily agree with all his policies or his style of political governance, but I am proud to be a Singaporean because of him.

The writer is a former corporate banker and stockbroker who is now a private investor.