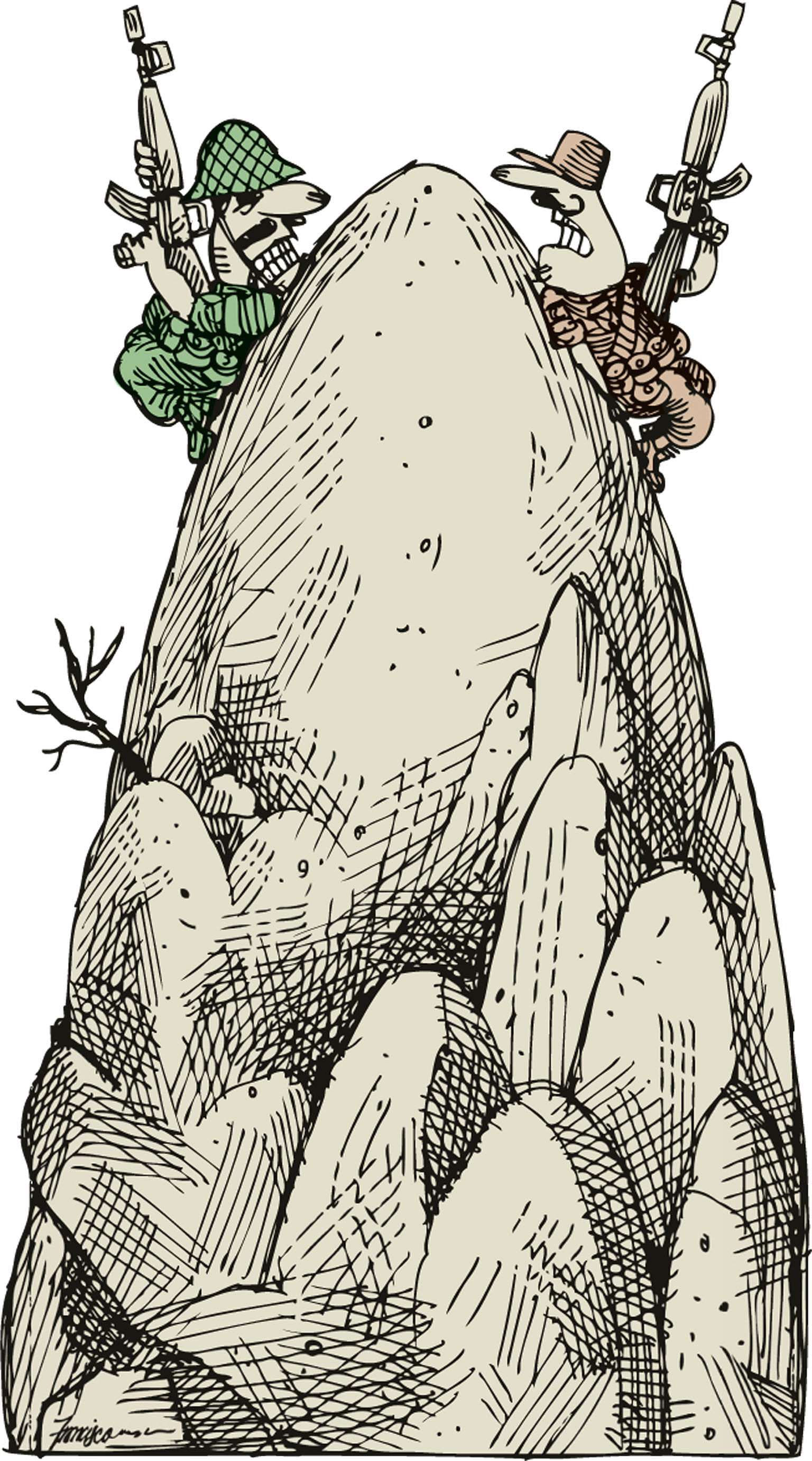

Every half-dozen years or so, India and Pakistan ties come to a boil over the canker that is Kashmir, the issue that's caused most wars between the sub-continental siblings, and may do so again.

This week, after 18 Indian soldiers were wiped out by a militant attack on a camp in Uri, one of the oldest Kashmir garrisons, global attention is swinging back to the sub-continent and away from China's maritime disputes with its neighbours. The Uri outrage, blamed on the Jaish E Mohammed terror group, was clearly timed for the start of the United Nations General Assembly, when world leaders congregate in New York City. New Delhi says the Jaish is supported by the Pakistani "deep state", which is widely known to have supported militant groups in the past to further its strategic interests in Kashmir and Afghanistan.

If the intent, indeed, was to provoke India and muddy chances of a rapprochement with Islamabad, it has worked - almost. Mr Ram Madhav, a high-ranking figure in the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, has spoken of extracting a "jaw for every tooth". Hardline commentators in India are calling for New Delhi to curb water supplied to Pakistan through a 1960 treaty that has impressively withstood a series of disruptions in bilateral ties. Although no credible evidence has yet been produced by India to directly link the attack with the Pakistani state, Home Minister Rajnath Singh has called Pakistan a "terrorist state".

Across the border, Pakistan's army chief has met with his top commanders and its Prime Minister, Mr Nawaz Sharif, has raised the issue at the UN. The Pakistani press says Chinese Premier Li Keqiang has described his nation's ties with Pakistan as like between "iron brothers" and assured Islamabad that Beijing would speak up for the Pakistani cause at every international forum.

The statements from the Indian Army have an ominous ring. Its director-general of military operations this week told the media that India "reserves the right to respond to any act of the adversary at a time and place of our choosing".

How did things get to this point? Like several other Indian leaders, including his own party elder, Mr Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Prime Minister Narendra Modi came into office thinking it was within the scope of his talent and personality to make peace with Pakistan. Mr Sharif was invited to attend the ceremony at which Mr Modi was installed. Moving things along, over Christmas last year, the Indian leader himself dropped in at the Sharif estate like an old friend to participate in a family wedding.

Any hope that the bonhomie would lead to improved ties quickly dissipated though when a week later, militants, said to have been sent by the Jaish, attacked an Indian Air Force base in Pathankot, a forward air base in Punjab. The militants were confronted and killed, while India lost four servicemen. Several other attempts on military installations have been made since, and quelled without major losses. But the Uri attack was clearly successful. The question is whether this was a pure terrorist attack, or one backed by the so-called deep state, which is wary of closer ties with India.

That's because Pakistan's dalliance with militant groups, such as Jaish and the Kashmir-focused Lashkar E Taiba, are too well-documented to deny. Jaish and Lashkar leaders move freely around Pakistan. Indeed, the latter was released on bail last year after being held for years by Pakistan's security network over Indian accusations that he masterminded the 2008 terror attack on Mumbai. That outrage claimed 166 lives, including that of a young Singaporean woman.

But Uri marks a key turning point - much more than is recognised. Mr Modi's Pakistan policy is in shambles and he is under pressure from India's media, retired military hands and influential analysts to take strong retaliatory action.

Mr Modi's apparent reluctance to be rushed - as a signal the Indian Air Force chief was not invited to a top-level national security council meeting chaired by the Prime Minister earlier this week - makes the popular Indian leader, who came into office boasting of a 56-inch chest, look decidedly less macho than he would like to be.

But this restraint, if indeed it is that, is well-advised. For one thing, India does not wish to be hyphenated with its nettlesome neighbour at a time when it is eyeing strategic parity with China and a larger global profile. It is also fully aware that the current surge of investment flows it is enjoying, and its claim to being the world's fastest-growing major economy, may both be at risk in the event of a conflict.

Mr Modi must surely also know that overwhelming as India's conventional power is, there is a real chance that Pakistan may use its nuclear weapons if faced with massive and certain defeat. It is one thing for a prime minister like Dr Manmohan Singh to order an attack, quite another for Mr Modi, whose roots are in hardline Hindu nationalism, to do the same thing. Pakistan was created on the theory that Hindus and Muslims are "two nations" and any aggression from a Modi government will play to stereotypes of a "Hindu" strike at the country, a humiliation that the military chiefs of Pakistan simply will not be able to swallow.

Besides, India is disadvantaged, even in a limited nuclear exchange. Aside from the fact that Pakistan has more nuclear weapons, that nation's slim geographical profile and the wind patterns on the subcontinent for most of the year mean that any radioactive fallout from an Indian nuclear counter strike will swiftly blow back into the border states of Punjab, India's granary, and Mr Modi's own home state of Gujarat, which produces most of the nation's cotton. One reason Gujarat, despite being a border state, has so successfully drawn massive investments - including world-class petrochemical complexes - is that the threat of war had receded over the decades.

The wider geopolitics of the region are also swiftly changing. In past conflicts, China stood aside, despite its "all-weather friendship" with Pakistan. But the Chinese are building a US$46 billion (S$62.3 billion) economic corridor through Pakistan-held Kashmir all the way to the warm-water port of Gwadar in Balochistan that is tied to its own future security. India has made clear it is discomfited by this development and Mr Modi has reached out to the disaffected people of both Gilgit, in Pakistan-Kashmir's northern areas, as well as Balochistan, sending a clear message to Islamabad and Beijing that it has buttons to press. This has led to counter warnings from commentators in China.

For all these reasons, India cannot be confident that the Chinese will take a hands-off approach this time, even if New Delhi's swiftly developing ties with Washington provide it a degree of comfort.

So, even as Mr Modi says that the people behind the Uri attack will "not go unpunished", his options are limited. Given that China lays claim to all of the eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, India dare not make a military move until the snows fill the mountain passes of the Himalayas, making it more difficult for the Chinese to threaten a descent from Tibet into eastern India to ease pressure on Pakistan.

What of the Kashmiris caught in the middle? The Kashmir Valley is witnessing unrest on a scale not seen in a quarter-century, and that is partly on account of Mr Modi's own policies. Soon after he took charge, he implemented a tough, uncompromising policy on Kashmiri separatists under the advice of his National Security Adviser, Mr Ajit Doval. Then, in the BJP's eagerness to control more and more states, it entered into a coalition arrangement with a key Kashmiri party, accepting the junior role in the partnership but, nevertheless, acquiring the sheen of having "captured" the only Muslim-majority state. That bred resentment.

Things decidedly turned for the worse from July, when Indian security forces rubbed out a militant commander named Burhan Wani, a popular figure barely into his 20s. To quell mounting protests - Kashmiris these days tend to adopt the stone-throwing tactics of the Palestinian intifada, provoking the police and the military to retaliate - the Indian state has stepped up repression on the Kashmiri population.

Although its security forces are significantly better behaved now than they were a quarter century ago, and more sensitive to human rights concerns, the brutality is nevertheless severe. The death toll has mounted by the week and tops 70. Thousands of Kashmiris have suffered damage to the eyes and other parts of the body from the pellets used to quell demonstrators. In the Valley, some are calling 2016 the "Year of Lost Eyes".

New Delhi's approach has been to put the blame for all this squarely on Pakistan's shoulders. While some of it is clearly warranted, India seems blind to local sentiments in the Kashmir Valley.

New Delhi ought to realise that it has fumbled Kashmir and quite badly. It should count itself fortunate that the issue escaped mention in UN chief Ban Ki Moon's farewell address to the world body, which included a recap of the various conflicts that happened under his watch, including Syria, Palestine, Myanmar and Sri Lanka. But it may be a matter of time before it becomes an international issue all over again.

As a first step, it would be wise for it to revisit the so-called "Doval Doctrine" of toughness. Then, come January, Foreign Secretary S. Jaishankar finishes his two-year tenure, offering the Prime Minister an opportunity to move him into a larger national security role. Mr Doval's responsibilities could then be split so that the accomplished diplomat can take charge of the external dimensions of security, leaving Mr Doval to focus on internal security, his speciality.

Still, that leaves worry over that threat to respond at "a time of our choosing". My fear is that India may be heading towards borrowing from its estranged neighbour's own playbook and preparing for a constant state of low-intensity conflict using covert means. In December 2014, a few months after Mr Modi took office, Afghan, Arab and Chechen militants infiltrated the Army Public School in Peshawar and murdered some 130 children, mostly offspring of Pakistani military officers, peacefully sitting their exams.

It may have been mere coincidence but many in Pakistan took note that the attack coincided with the anniversary of the birth of Bangladesh in 1971 as a breakaway state from Pakistan. Covert Indian assistance had aided that process.

So far, the Indian calculation has been that a splintered Pakistan would be more dangerous than its current avatar - a nation of mostly moderate Muslims that uses terror to suit its purpose, but which also had had its own share of suffering from terrorist attacks, many of which were perpetrated by the dark forces it had itself nurtured for strategic ends. That perception held even after the Mumbai attacks delivered India its last major provocation.

Should the new Indian leadership redo the sums, it might get a different result this time. And that would make for a more dangerous sub-continent, if not the world.