In less than two months, about 200 nations are expected to finally agree to a sweeping deal that aims to limit the intensity of future climate catastrophes. The world is living dangerously and urgently needs a deal that commits all nations to cut carbon dioxide emissions blamed for heating up the air and the oceans.

Most of us can see the weather is changing and would agree with scientists that pollution from our cars, power stations and industries is affecting natural weather patterns. It seems increasingly obvious that the world needs to come together to make economies greener and far less polluting.

Any deal likely to be sealed in Paris, though, will have been hard won and the result of more than two decades of often nasty and divisive discussions. The United Nations-led talks in Paris from Nov 30 to Dec 11 will be the culmination of years of exhaustive and frustrating diplomacy and nations are literally burned out from the process which has repeatedly faltered in the quest to seal a global climate deal.

Fortunately, the diplomatic atmosphere has improved since the nadir of the chaotic Copenhagen climate talks in 2009 that was meant to seal a global deal but instead triggered a panicked effort by world leaders right at the end. That effort yielded a weak and widely criticised accord that didn't unite the globe against climate change.

Years of patient engagement and coaxing since then by the UN and expert diplomacy and careful management of expectations by the French government, which is hosting the upcoming talks, have greatly improved the mood and prospects for Paris.

There is less of the bitter and deep mistrust between rich and poor nations, helped in part by the strong climate commitments by China and the United States, the world's two top carbon dioxide polluters, and recent decisions to improve climate financing for less developed nations.

And the message of urgency to do a deal, plus the increasing evidence of rapid warming, has added pressure to reach an agreement.

But a major question remains. With the desperation to do a deal in Paris, just what sort of deal will it be? Critics say the Paris pact will be weak, if not fatally flawed, because it will rely on voluntary pledges and most likely contain no sanctions for nations that fail to act on their promises.

Under the current process, all nations participating in the talks have to submit their national climate action plans to the UN. These plans, called Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), set out a range of actions on tackling greenhouse gas emissions, depending on the country's state of development, capacity, access to finance and impact on the economy. Wealthier states are expected to do more to cut emissions, such as setting clear reduction targets, while poorer, more vulnerable nations might opt for renewable energy or energy efficiency targets.

So far more than 150 nations comprising over 90 per cent of mankind's greenhouse gas emissions have submitted their INDCs.

The UN says this system is fairer because nations can tailor their actions, which must be more ambitious than past climate pledges, to their abilities and that all nations have agreed there will be no backsliding.

To be effective, though, the pledges must be reviewed and ramped up over time, say every five years, to ensure the emissions belt-tightening continues.

India, China and others strongly oppose any regular outside review of their pledges, saying this would be an assault on their sovereignty. The compromise solution could be that the UN conducts a regular aggregate review of all pledges in the hope of pushing countries to offer deeper cuts.

That reliance on trust, though, has some worried. Previous treaties that rely on voluntary measures haven't always worked. And within the talks process, there is virtually no appetite for a system that would punish or sanction countries that break their climate vows.

Indeed, the now defunct Kyoto climate pact, which did have provisions to punish rich nations that reneged on their targets, proved to be toothless when the US, Canada and Japan abandoned the treaty.

Mr Yvo de Boer, the UN's top climate official at the time of the Copenhagen talks, was quoted by Reuters this month as saying that ditching sanctions was, ultimately, part of the price of getting a broad, global agreement.

"The sting has been taken out of the process... That means the chances of a deal are much better," said Mr De Boer, who now works for the Global Green Growth Institute in South Korea.

In a commentary for the journal Nature this month, Dr David J. C. MacKay, professor of engineering at the University of Cambridge in Britain, said success requires a common commitment, not a patchwork of individual ones.

"Negotiations need to be designed to realign self-interests and promote cooperation. A common commitment can assure participants that others will match their efforts and not free-ride," Dr MacKay and his colleagues wrote.

For the moment, that common commitment is not on track to save the world from greater extremes of deadly weather that could ruin crops and global fish stocks, threaten water supplies, wreck coastal cities and trigger mass migration.

The UN and the European Commission say the current crop of INDCs commit the world to warming at least 3 deg C by the end of the century, and possibly more. The agreed UN goal is to limit warming to below 2 deg C to avoid the worst of climate change impacts.

The UN is hoping that the Paris gathering will agree on a robust system to review national climate pledges and that nations will feel compelled to progressively make deeper emissions cuts in step with other countries.

That is a big ask and a big hope.

Nations need to see that fighting climate change is in their long-term national interest. The good news is this is already happening, though it needs to happen faster.

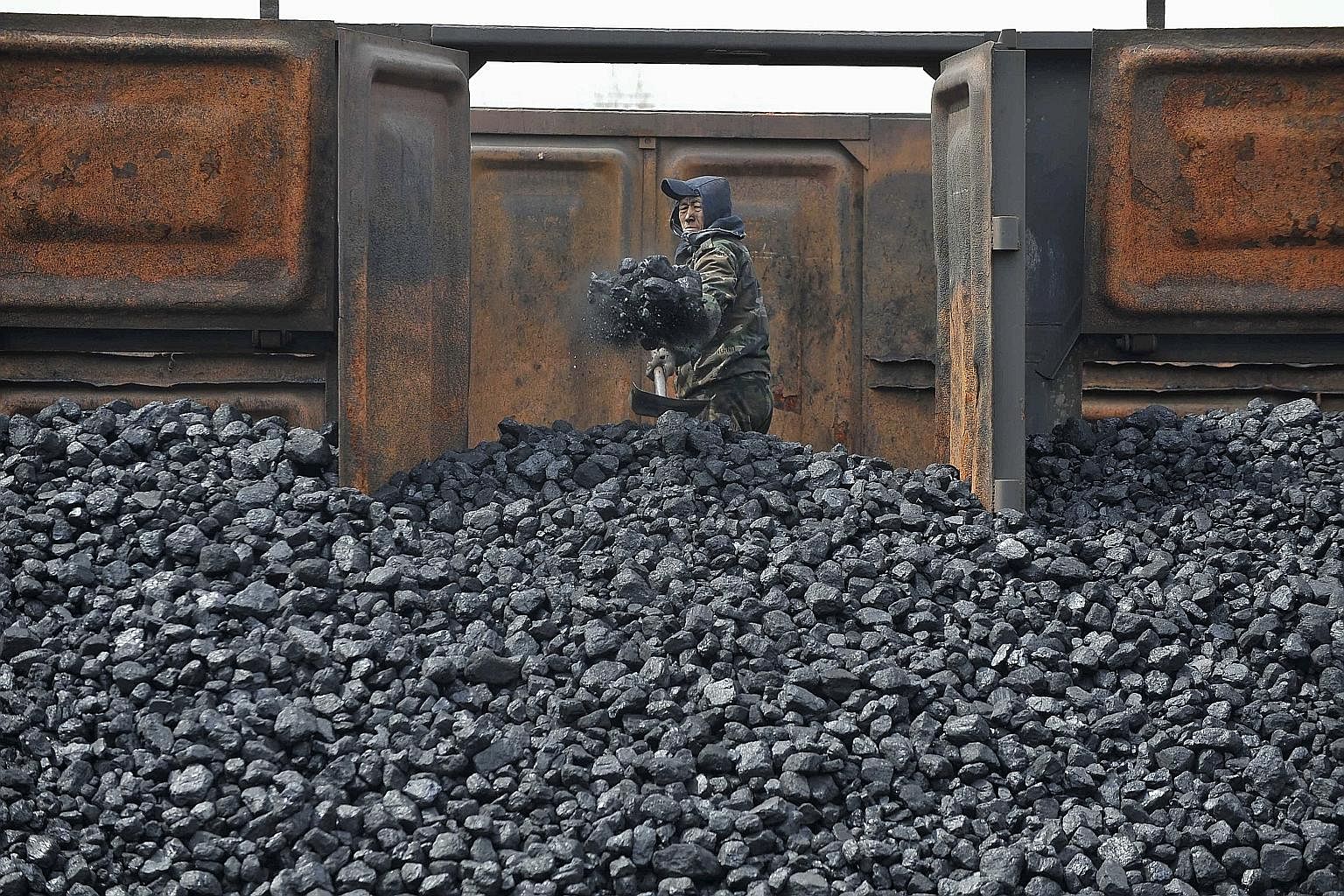

Many big polluters, rich and poor, are investing heavily in renewable energy as an alternative to fossil fuels. Green energy can connect people more quickly to local or national grids, as well as improve the health of millions of people. Faced with choking air pollution, China is starting to shift away from coal-fired power plants and is also forcing dirty industries to clean up.

Greener energy is also much more affordable now and a big job creator, taking the sting out of the old narrative that renewables were expensive and cost the jobs of power sector workers.

More than this, the science and impacts of climate change have become resoundingly clear and the stance of sceptics increasingly exposed as dishonest and self-serving.

The weather extremes we witness now are set to become more extreme unless the globe takes strong collective action. While the outlines of the deal in Paris might be seen to be weak, it at least will provide nations with a tool to progressively ratchet up efforts to cut emissions.

The UN sees a Paris agreement as the start of a decades-long process to fight climate change, not a one-shot deal.

And for those nations that want to free-ride? Peer pressure, international shaming and a strong kick from a very angry Mother Nature might be enough to get them back into line. Here's hoping.