On Aug 31, 1956, Malayan Railwayman David Colundasamy Aloysius John had a heart attack in Kuala Lumpur and died. He was 47. He missed Merdeka Day by exactly a year, so never got to see the country of his birth gain independence from Britain.

He also missed my third birthday by 24 days. So I grew up knowing little of the man who was my father. I can't describe the sound of his voice or the look on his face when he was happy, sad or furious. I don't know if he sang in the bathroom like I do.

What I have are some small black-and-white photographs of my father that I have looked at again and again, as a child growing up and as an adult and that I brought with me to Singapore when I moved from Kuala Lumpur in 1980.

One, in particular, fascinated me for the longest time. It shows my father standing in front of a brick lighthouse, unsmiling, his hair blown by the breeze, his hands in the pockets of his baggy cotton trousers.

He posed for that picture in Tumpat, Kelantan, at the final stop of the Malayan Railway's eastern line that once ran all the way from Tanjong Pagar in Singapore to this north-eastern corner of the Malay peninsula.

I have been drawn to this picture countless times. My father did not know that day in 1952 that he would have a son the following year, or that his life was so near its end.

It has taken me a long time to go in search of my father's lighthouse. I'd thought of doing so many times, but it was only early this year that I finally made the trip as if it was something I needed to do before it got too late.

The Internet told me the lighthouse was still standing, but I didn't know what I hoped to find. My old friend Chin Kin Yong drove with me from Kuala Lumpur to Kelantan in March and one morning we made our way to Tumpat, 20 minutes outside the state capital, Kota Baru.

We had reached Kelantan by driving diagonally across the Malaysian peninsula from Kuala Lumpur, cutting through the main mountain range, and it took us about eight hours with stops along the way.

The train journey would take almost a day and you'd have to first ride south from Kuala Lumpur on the west coast all the way to the railway town of Gemas in Johor, change trains and then travel all the way up the east coast to the line's end. At Tumpat, the rail tracks run a short distance from the station platform before coming to an abrupt stop. Then there's just gravel and a fence.

MY FATHER'S BEST FRIEND

In February 1952 my father was in Tumpat with his Malayan Railway colleague and friend Henry Lang Taylor, and they would have taken the long train ride from Kuala Lumpur to get there.

I don't know how long they spent in Tumpat, but they stayed at the rest house for Railway officers when the 14 black-and-white photographs were taken.

I don't know who the photographer was, but it is clear from the way these two men appear so comfortable striking various poses indoors and outdoors that they were the best of friends.

Both were born in 1909 in colonial Malaya. Both were educated at De La Salle schools run by the Christian Brothers - my father at St Francis' Institution in Malacca, and his friend at St Xavier's Institution, Penang. Both survived World War II and the Japanese Occupation. Both worked as Malayan Railway accounts inspectors, visiting stations across Malaya to audit the books.

Both men also married the same woman, my mother Agnes.

When my father died, he left my mother a widow at 26 with four young children - my older sister Barbara and me, and our cousins Denis and Audrey whom my parents had adopted after their father, my mother's eldest brother, died.

Our lives were turned upside-down by my father's sudden death. My sisters were put in a boarding school run by Catholic nuns and my mother who had never worked outside the home took a job as a telephone operator at Braddell & Ramani, a Kuala Lumpur law firm.

There was an upheaval and breaking away from my father's side of the family and we would never be close. He was the second of five brothers and although three survived him, none figured in our lives in a good way after his death.

It was my mother's youngest brother Charlie, a clerk in his early 20s and not yet married, who helped most by letting us move in with him in his government quarters in Jinjang North New Village outside Kuala Lumpur.

Our lives changed again on July 4, 1959, when my mother married Henry Lang Taylor, my father's best friend and the other person in those Tumpat photographs.

My stepfather was Eurasian, Catholic and divorced. He had lost a young son in the war, and his ex-wife had taken their other son, Errol, to live in Perth, Western Australia. He almost never talked about his earlier life.

When my mother married Henry Taylor, it set tongues wagging, to say the least, because in 1959 it was simply not the done thing for a young, Indian, Catholic widow to go off and marry a divorced man. My mother never forgave the people who disapproved.

My stepfather was a homebody and everyone who got to know him could see that he was a good man; it surely takes someone special to marry a widow with four children.

He brought our family together, upgraded our lives by taking us to a new home in the sprawling Sentul railway settlement with its hierarchy of housing types ranging from terraced lines of the smallest homes to double-storey brick bungalows fronting a golf course.

You knew you were in a railway community because the houses were painted a standard cream and brown. You can still spot colonial-era Malayan Railway quarters in towns across the peninsula by their templated designs and colour scheme.

Our new home was a raised bungalow with a large compound in Graeme Road, where the Railway's mid-level executives had their houses. It was my stepfather who decided I should attend St John's Institution, the premier Christian Brothers boys' school in Kuala Lumpur, and that would have the most long-lasting effect on my life. He and my mother had two daughters, and our lives carried on.

MEMORIES OF MY FATHER

Because Malaya gained independence on Aug 31, 1957, my father's death anniversary was a public holiday and every year we would make the trip to the Cheras cemetery on Kuala Lumpur's outskirts to leave flowers and light candles at his grave. I remember more of the cemetery trips than of my father.

There are people who say their earliest memories stretch all the way to infancy, but I'm not one of them. I've sometimes wondered if the trauma of his sudden passing wiped out everything I knew of him to the extent that I remember nothing at all.

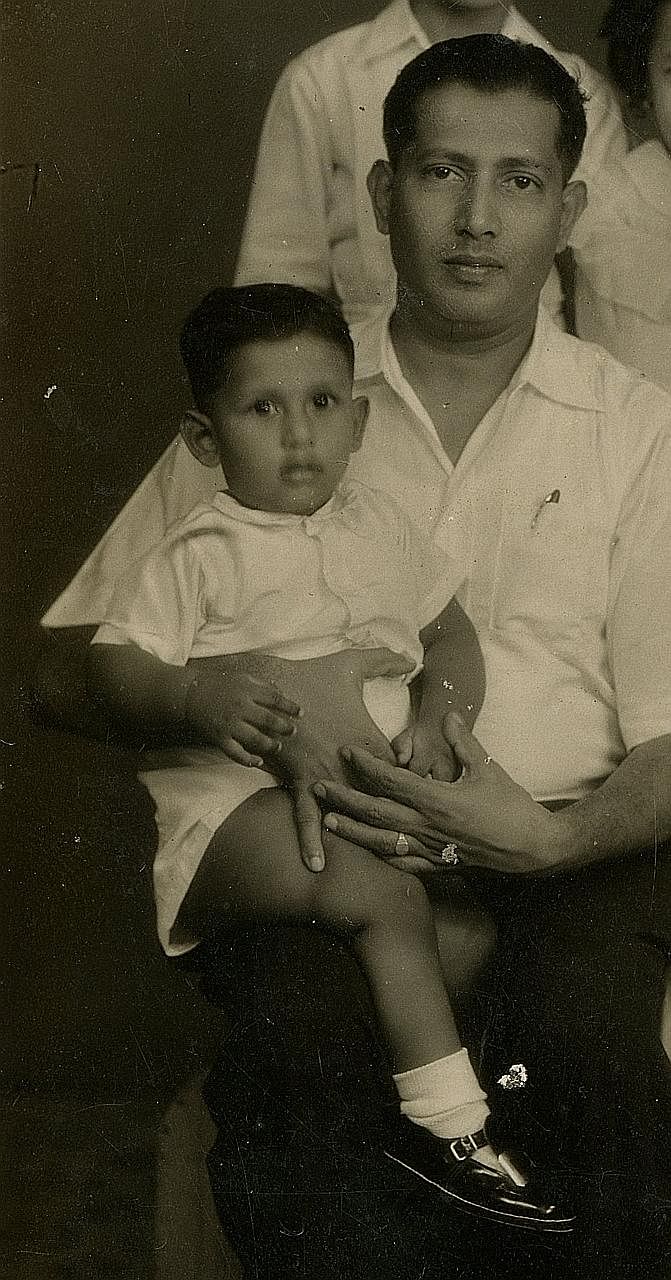

In one family picture taken in a photo studio, I am a toddler on his lap, and he appears calm and unsmiling. We have no informal photographs from the 1950s, so I don't know what he was like relaxed, in his home clothes. I don't know if he ever tossed me in the air or kissed me.

My mother was not given to talking about my father. They were first cousins, and although it was not uncommon at the time among Malayalee Catholics for first cousins to marry, my parents did not marry for love. She was 16, he was 20 years older, and one day after the war he decided it was time to have a wife and chose her. At the same time, her elder sister Beatrice married his youngest brother Michael.

Sometimes my mother let on that my father was a dramatic teller of stories who could hold an audience spellbound. Or that he had a terrible temper.

She often described sudden widowhood as the time when she realised she did not know how to do anything because my father had taken care of all important household matters, and even went to the market for the family.

He was always running late to catch the train that took him from our railway quarters to his office, she recalled once. But he worked hard and was honest, which was why he did not leave much when he died. Random snippets from a 10-year marriage.

My stepfather shared even less about his good friend.

As I grew up, older folk who knew my father would sometimes remark that I looked just like him and for some reason that always felt good. And, as if this was all I needed to know about him, they would tsk sadly and add: "The good die young."

I did not long to know more about my father, was never aware of a hole in my heart that needed to be filled and did not ask questions when I could.

But coming across his old photographs, I would always pause, and the older I got, the longer I lingered over the details of my father's features, his eyes and eyebrows, the shape of his lips and fingers, and the bump on his forehead.

Sometimes it frustrated me that all I could see was a pleasant-faced Indian man who rarely smiled for the camera.

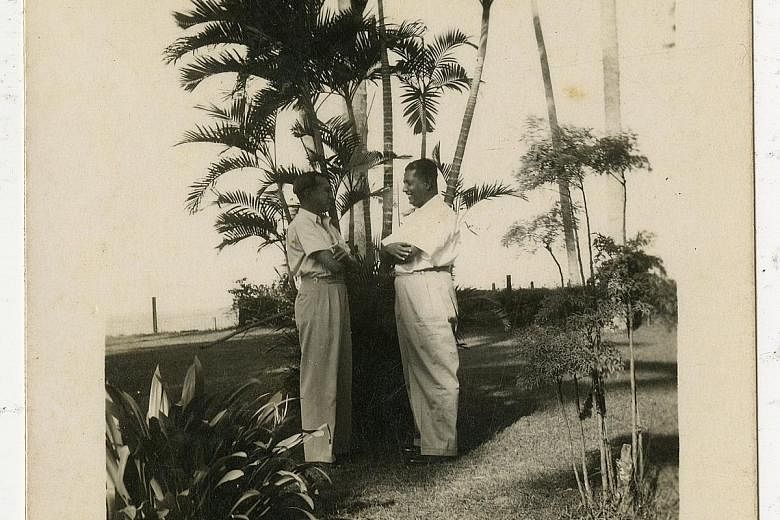

The Tumpat pictures are precious for showing my father and stepfather together. They are not yet 43 years old and they are relaxed and clearly happy despite the absence of smiles.

There are pictures of them at the rest house, having a cup of tea, lounging in large low armchairs that were the Railway's standard-issue furniture. There they are outdoors, standing with arms folded or hands in their pockets, or holding boxy briefcases and pretending to be setting off on a mission.

There are also shots in a park and at the seaside, with Kelantanese fishermen in the background. My father wears a grin in only one picture, where he and his friend stand facing each other in front of some palm trees. The hand-written caption on the back says: "A chin-wag in the garden of the Railway Rest House - Tumpat." It is dated Feb 19, 1952.

It is March 18, 2016 and nearly 60 years after my father's death when I arrive in Tumpat.

As Kin Yong and I drive along the road to the train station, I feel an odd excitement at spotting the first Malayan Railway houses in their faded cream and brown.

The station itself is an unexceptional building, but on its platform there are reminders of an earlier era, including Made-in-England wrought-iron roof trims that would have been there when my father visited.

We get directions and find my father's lighthouse, now marooned within the compound of the station's maintenance workshop. In the decades since my father was here, the coastline has moved and houses have sprouted where the sea used to wash up.

A guard stops me from going to the lighthouse because this is a restricted area now, but he relents after I show him my father's photo on my iPhone and Kin Yong assures him we will be quick. I get my own pictures with my father's lighthouse.

A little later, we find the very bungalow where my father and stepfather lounged with cups of tea and posed for pictures.

Amazingly, after all these years, it is still the rest house for visiting Railway officers.

And then we leave the place.

Afterwards I am unable to describe that morning in Tumpat when people who knew of my trip ask: "So did you find your father's lighthouse?"

Instead, I return again and again to the old photograph of my father and the lighthouse. In it, he is alone and stares directly at the camera with no trace of a smile on his face.

What if he had known that day that he had only four more years to live? How differently would he have spent the remaining time? What would he have stopped doing, started doing? Who would he have treated better?

And after his son arrived, would he have cared that the boy would grow up never knowing him, and might that have prompted him to write a letter to tell me who he was and how he hoped I might remember him?

Would he have described how he and his brothers were orphaned young, or revealed what broke for them along the way that kept them so separate as adults, seemingly uncaring and indifferent to one another, never close?

Would he have told me who he loved truly, and how and why?

Would my father the storyteller have told me a story? His story?

•The writer is the former Deputy Editor of The Straits Times. He is the author of a collection of personal columns Good Grief! Everything I Know About Love, Life & Loss I Wish Somebody Had Told Me Sooner. This article first appeared on his website, alanjohn.net