PASADENA (Maryland) • Mucking around with sand and water. Playing Candy Land or Chutes and Ladders. Cooking pretend meals in a child-size kitchen. Dancing on the rug, building with blocks and painting on easels.

Call it Kindergarten 2.0.

Concerned that kindergarten has become overly academic in recent years, this suburban school district south of Baltimore, Maryland, is introducing a new curriculum in autumn for five-year-olds. Chief among its features is a most old-fashioned concept: play.

"I feel like we have been driving the car in the wrong direction for a long time," said Ms Carolyn Pillow, who has taught kindergarten for 15 years and attended a training session in Baltimore on the new curriculum last month. "We can't forget about the basics of what these kids need, which is movement and opportunities to play and explore."

As American classrooms have focused on raising test scores in mathematics and reading, an outgrowth of the federal No Child Left Behind law and interpretations of the new Common Core standards, even the youngest pupils have been affected, with more formal lessons and less time in sandboxes.

The law now requires public school students to pass standardised mathematics and reading tests, and punishes their schools or teachers if they do not. But these days, states from Vermont to Minnesota to Washington are again embracing play as a bedrock of kindergarten.

Like Anne Arundel County in Maryland, Washington and Minnesota are also beginning to train teachers on the importance of so-called purposeful play - when teachers subtly guide children to learning goals through games, art and general fun.

Vermont is rolling out new recommendations for kindergarten through third grade (for eight- and nine-year-olds) that underscore the importance of play.

And North Carolina is encouraging teachers to evaluate paintings, scribbles or block-building sessions, instead of giving quizzes, in assessing the reading, maths and social skills of kindergarten pupils.

But educators in low-income districts say a balance is critical. They warn that unlike children from affluent families, those from poorer ones may not learn the basics of reading and maths at home and may fall behind if play dominates so much that academics wither.

"Middle-class parents are doing this anyway, so if we don't do it for kids who are not getting it at home, they are going to start at an even greater disadvantage," said Ms Deborah Stipek, dean of the Graduate School of Education at Stanford.

IMPROVING TEST SCORES

Across the United States, many schools in recent years have curtailed physical and art education in favour of longer blocks for reading and maths instruction to help improve test scores. The harder work began even in kindergarten.

Most recently, more than 40 states have adopted the Common Core standards for reading and maths that in many cases are much more difficult than previous guidelines. In some school districts, five-year-olds are doing what first- or even second-graders once did, and former kindergarten staples such as dramatic play areas and water or sand tables have vanished from classrooms, while worksheets and textbooks have appeared.

A study comparing federal government surveys of kindergarten teachers in 1998 and 2010 by researchers at the University of Virginia found the proportion of teachers who said their pupils had daily art and music sessions had fallen drastically. Those who reported teaching spelling, the writing of complete sentences and basic maths equations every day jumped.

The changes took place in classrooms with pupils of all demographic backgrounds, but the study found that schools with higher proportions of low-income children, as well as schools with large concentrations of non-white children, were even more likely to cut back on play, art and music, while increasing the use of textbooks.

THE VALUE OF PLAY

Experts, though, never really supported the expulsion of playtime.

Using play to develop academic knowledge - as well as social skills - in young children is the backbone of alternative educational philosophies like those of Maria Montessori or Reggio Emilia.

And many veteran kindergarten teachers, as well as most academic researchers, say they have long known that children learn best when they are allowed ample time to go shopping at a pretend grocery store or figure out how to build bridges with wooden blocks. Even the Common Core standards state that play is a "valuable activity".

But educators point out that children are also capable of absorbing sophisticated academic concepts.

"People think if you do one thing, you can't do the other," said professor of education Nell Duke at the University of Michigan. "It really is a false dichotomy."

Ms Manuela Fonseca, Vermont's early-education coordinator, said her state was trying to emphasise the learning value of play in its new guidelines. "Before we had the water table because it was fun and kids liked it. Now we have the water table so that kids can explore how water moves and actually explore scientific ideas," she said.

PACKED AGENDAS

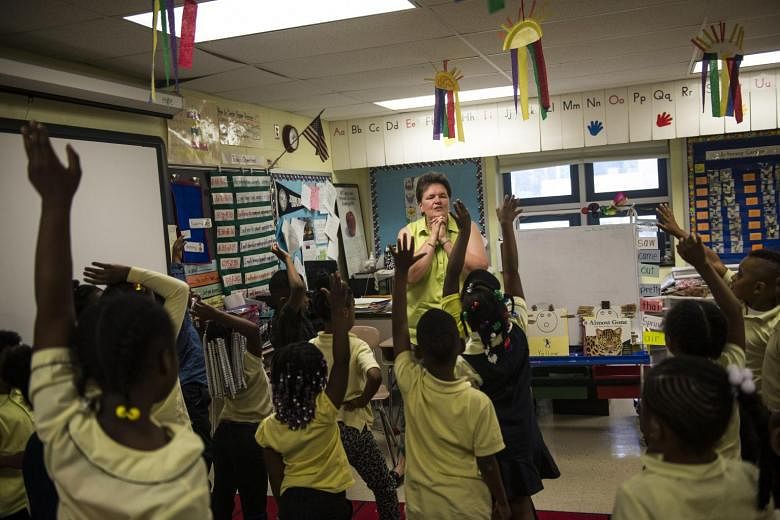

Still, teachers like Ms Therese Iwancio, who works at Cecil Elementary School in Baltimore's Greenmount neighbourhood, where most children are from low-income families, say their students benefit from explicit academic instruction. She does not have a sand table, play kitchen or easel in the classroom.

"I have never had a child say to me, 'I just want to play'," said Ms Iwancio, who has been a teacher for two decades. On a recent morning, she asked her pupils to read aloud from a simple book. On the wall hung a schedule for the day, with virtually every minute packed with goals like "I will learn sight words" or "I will learn to compose and decompose teen numbers".

Jayla Stephens, six, said she liked school because "you get to do a lot of work and you will get better".

TIPS FOR TEACHERS

In the neighbouring, more affluent Anne Arundel County, 321 kindergarten teachers last month attended training sessions on the new curriculum. Required each day: 25 minutes of recess, 20 minutes of movement, 25 minutes in play centres.

The district is buying sand or water tables, blocks, play kitchens, easels and art supplies for classrooms.

Teachers were given tips on how to be more creative in academic lessons, like tossing a ball printed with different numbers to teach maths.

"We don't think that rigour negates fun and play," said Ms Patricia Saynuk, coordinator of early childhood education.

Ms Traci Burns, who has taught kindergarten for the past five years at Annapolis Elementary School, said she was looking forward to retrieving previously banished easels.

"With the Common Core, this has been pushed and pushed and pushed that kids should be reading, sitting and listening," she said. "Five-year-olds need to play and colour. They need to go outside and sing songs."

At Hilltop Elementary, a racially and economically diverse school in Glen Burnie, Maryland, Ms Melissa Maenner said she had found that teaching kindergartners too many straightforward academic lessons tended to flop.

"They are five," she said. "Their attention span is about five minutes."

NEW YORK TIMES