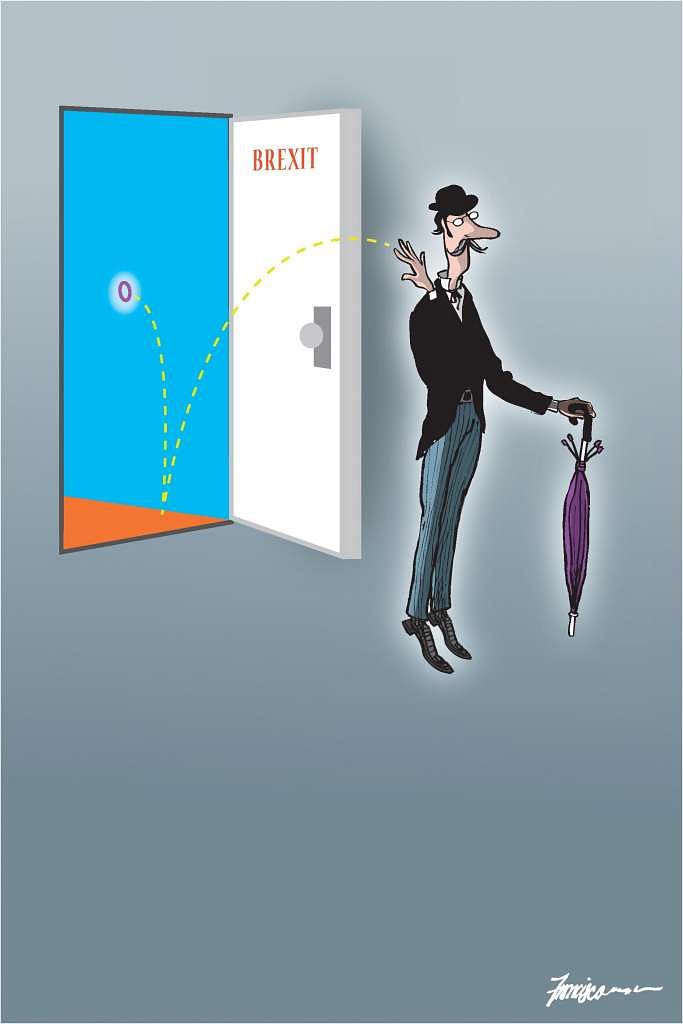

LONDON • Britain's decision to leave the European Union (EU) is the biggest political blow to the European project of forging greater unity since World War II. But it is also a leap into a legal dark hole, a journey through an uncharted period in European history.

For although some guidance as to what has to happen in the "divorce" deal between Britain and the EU is specified by existing EU treaties, the broader questions of what should be discussed and what should be included in the deal will have to be improvised. Two conclusions are, however, already evident: what is agreed between Britain and the rest of the continent will shape Europe's character for a long time, and one wrong move by either side could well doom Europe to further mayhem.

For decades, EU treaties contained no specific mention of the possibility that a member state may choose to leave the Union. That did not prevent two territories which initially belonged to the EU from leaving. Algeria, which was an integral part of France, chose not to remain in the EU when it gained its independence in 1962. And Greenland, a possession of Denmark and the world's biggest island, decided in 1982 to withdraw from the EU, despite the fact that Denmark itself remained a member of the Union.

But neither of these two historic examples is relevant today. For the EU at that time did not entail as many obligations as it does now. And neither of the two territories which withdrew were self- governing. So, Britain's decision to leave is without precedent.

In theory, guidance of what needs to be done is contained in Article 50 of the so-called Lisbon Treaty, a 2009 document which acts as the EU's de facto Constitution. Under the provisions of that Article, once Britain notifies other member states of the EU that it wishes to leave the Union, the two sides have up to two years to negotiate before their divorce becomes final.

Sounds simple? Think again.

WHEN TO START PROCEEDINGS

The first complication is the way Britain appears to have decided to withdraw. That decision was, supposedly, taken in the referendum which took place last week. Only that it didn't. For in strictly legal terms, the referendum was purely advisory, since the British Parliament has supreme constitutional powers and it is only Parliament which can decide the country's fate.

Theoretically, the British Parliament can choose to ignore the referendum's results altogether for, in strictly legal terms, this was nothing but a glorified opinion poll. Parliament won't ignore the referendum for political, rather than legal, reasons but European leaders who believe that Britain can start the divorce negotiations as early as this week are simply wrong; these cannot take place until a British parliamentary mandate is obtained.

More importantly - and as some European leaders are discovering to their huge frustration - the decision on when to start the negotiations to leave the EU rests entirely with Britain, rather than with any European institution or government. For as Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty puts it very clearly, "a member state which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention". So, unless that notification arrives, no negotiation can start.

British Prime Minister David Cameron, who resigned in the wake of the referendum, has already announced that he proposes to leave the start of the negotiations to his successor. That means that talks on Britain's departure from the EU cannot start until October, for it takes that long for Britain's ruling Conservative Party to elect a new leader, who will then become the country's prime minister.

Many EU leaders are furious about this delay. "This process should get under way as soon as possible so that we are not left in limbo but rather can concentrate on the future of Europe," says German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier; "I would like to get started immediately", adds Mr Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, the EU's executive body.

Meanwhile, Mr Martin Schulz, president of the European Parliament, has announced that EU lawyers are looking at ways to bypass the need to wait for Britain to trigger off the negotiating process, in order to speed up Britain's exit; he doubts that the decision of when to start the negotiations is "only in the hands of the government of the United Kingdom".

One rumour making the rounds in European capitals is that EU lawyers could claim that, when Mr Cameron meets his counterparts for a European summit this week and informs them that Britain has voted to leave the Union, that could be taken as a "notification" under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, and trigger off the negotiations.

But that's a classic example of lawyers being too clever for their own good, and it won't work, for the simple reason that Article 50 explicitly states that "any member state may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements", and it clearly is not accepted British constitutional procedure for a prime minister to serve a notice on such an important issue in a casual discussion with his counterparts. Therefore, as long as the British don't consider the notice as valid under their own constitutional arrangements, this can't be a notice under EU laws either.

There is no escape, therefore, from the conclusion that Britain controls the timing of when the negotiation procedure starts. And for the two years after the negotiations begin, Britain is also free to reject any departure deal offered to it, and still remain an EU member.

PUNISHING BRITAIN

The frustration of other EU leaders at these facts is understandable; their main concern now is to ensure that the British example does not inspire populists in other European countries to ask for similar referendums, and to show that the European project not only continues, but results in an even tighter Union. That means that Britain must be seen to be punished for its decision to leave, and the EU should initiate new projects of cooperation which bypass Britain.

But there are huge dangers in this approach. The British are going to suffer from their departure anyway; the country will slide into recession as foreign investment dries up and, while this does not preclude a subsequent rebound, it is unlikely that the British experience will be one others in Europe would rush to emulate. As a result, there is no particular need to "punish" Britain at the official level.

Furthermore, creating obstacles to a friendly divorce between the EU and Britain will hurt everyone in Europe, coming as it will on top of serious political problems on the European continent and continued financial difficulties.

And it is a rather weird argument that the best response to the rejection of European Union integration should be more EU integration. For such an effort will only divide Europe further and actually encourage more opposition to the EU.

The decision by Mr Steinmeier to call over the weekend a meeting of the original six founders of the EU is one of the worst possible initiatives: it has achieved absolutely nothing apart from producing an anodyne statement, but has infuriated many other EU countries which are growing increasingly suspicious that under the guise of isolating Britain, other EU member states will also end up isolated.

None of this is to absolve Britain of its responsibility for the current mess. Nor is there much doubt that the British cannot drag the negotiations over their departure forever; they must be reasonable with the timing, in as much as the Europeans should be reasonable in not demanding the immediate launch of the divorce talks.

Still, the best approach is to reach a magnanimous deal with Britain, one which allows the country to slide out as quietly as possible, in the hope that it may actually slide back into Europe at a none-too-distant future. And meanwhile, instead of pretending that the British are uniquely odd in wishing to leave the Union, EU leaders would do well to try and address the fall in the Union's popularity throughout Europe.

Some good may yet come of this disaster, but only if European leaders prove to be fiendishly clever, heroically patient and amazingly visionary. In short, they'll have to have all the qualities in short supply in Europe at the moment.