LONDON • Mr Donald Trump has shifted arguments many times, but he's been perfectly consistent on one point: his refusal to blame Russia for the repeated hacking of computers associated with Mrs Hillary Clinton, his Democratic opponent. "It could be Russia, but it could also be China. It could also be someone sitting on their bed that weighs 400 pounds," joked the Republican candidate for the United States presidency.

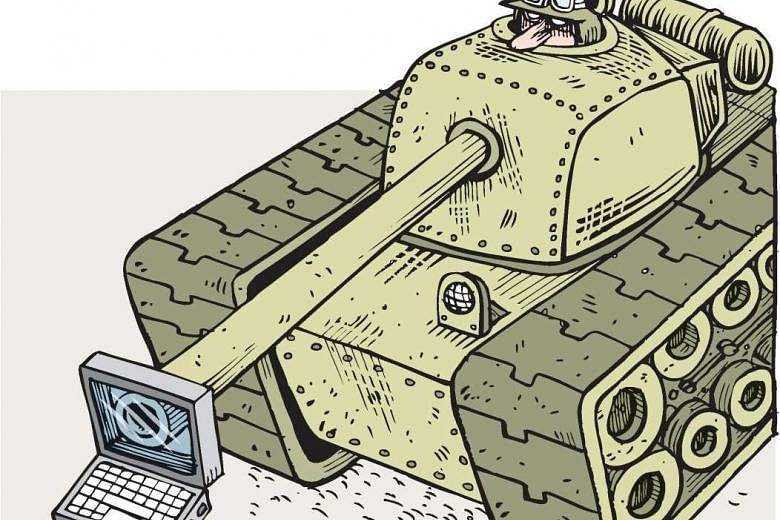

But for the armies of US intelligence analysts who have tracked and documented the Russian intrusion into American computer systems, Mr Trump's jokes remain monumentally unfunny. The current interference in America's electoral process has elevated cyber confrontations to an entirely new level. And the way the United States will retaliate for what has happened will define the management of cyber confrontations for years to come.

Cyber intrusions for spying purposes are not, of course, new: Recall last year's revelations that the computer systems of the US Office of Personnel Management were hacked - allegedly by China - leading to the exposure of sensitive records belonging to no fewer than 22 million current and former US federal employees.

Most of these actions, however, are considered "fair game" in the spying games governments routinely conduct against each other. As General James Clapper, who runs America's National Intelligence, honestly - and even gallantly - admitted soon after the hacking of the US personnel records was discovered: "You have to kind of salute the Chinese for what they did. If we had the opportunity to do that, I don't think we'd hesitate for a minute."

But what has been happening during the current presidential electoral campaign belongs to an altogether different league. None of the information stolen from the computer systems of the US Democratic National Committee or the pilfered e-mails of Mrs Hillary Clinton's campaign chairman John Podesta represents classic spying material. And much of the material was released to the public by outfits such as RT, the Russian state-funded broadcaster or the WikiLeaks organisation, whose idea of openness now consists of acting as a Russian propaganda outfit.

This was not, therefore, an intelligence operation as such, but a concerted and deliberate attempt to harm Mrs Clinton and influence the election of the person to occupy the most powerful post in the world's most powerful nation.

Understandably, the consensus among US government officials is that this intrusion cannot be allowed to go unpunished. And there is a broader demand for the US to strike back hard - hard enough to deter Russia or any other state from ever again attempting such a blatant interference in US domestic affairs. The snag is that most of the theories of retribution and deterrence invented during the Cold War do not apply to cyberspace.

CONCLUSIVE EVIDENCE

The question of attribution, of obtaining conclusive evidence as to who is responsible for any attack, is often cited as the biggest obstacle to contemplating any retaliation.

The Internet is a great leveller: Provided they know what they are doing, organised criminal gangs could inflict as much damage as nation-states, and a clever "couch potato" - the 400-pounder sitting on the bed, as Mr Trump put it - can be as destructive as a national intelligence agency. Add to this the fact that the geographic origins of almost any attack are disguised with a variety of technical means, and the difficulties of identifying the real culprits seem insurmountable.

But in reality, they are not. Western intelligence agencies, led by the US, have made great technological and analytical strides in identifying the origins of most cyber attacks, and although their conclusions may not be watertight enough to stand up to cross- examination in a court, they should provide governments with enough data about the identity of culprits.

In the case of the current intrusions, Mrs Clinton may have exaggerated in claiming that 17 US intelligence agencies identified Russia as the culprit, but at least 12 US intelligence agencies did point the accusing finger at Moscow, and that's conclusive enough.

The problem of attribution nowadays is not so much about finding the culprit, but about persuading voters that the real culprit of a cyber attack has really been identified and that retribution is required. For the identification methods are usually secret, and their technical complexity is almost impossible to explain, so people like Mr Trump have no difficulty in simply dismissing evidence as fabrication whenever that suits him.

But even if the US administration sets aside doubts expressed by people such as Mr Trump and his supporters and decides to respond to Russia's intrusions, it is not easy to see how this would deter future hostile operations. Applying the old, Cold War concept of deterrence does not work today either.

The concept of deterrence, of persuading an opponent not to do something you don't want by making a threat of unacceptable consequences, depends on being very precise about what the threat is, very clear about what retaliation will be expected and very transparent about the capabilities a country has to deter its enemies. Yet none of these ideas works in cyberspace.

A hostile cyber intrusion may take months or years before it gets detected, so an immediate response to an attack is almost never possible. But the longer the time-lag between the initial intrusion and the response, the less deterrent effect the action will have.

It is also impossible for the US to specify in advance what response it will give to every cyber attack. And it is equally impossible for the Americans to reveal the technologies they possess in order to deter enemies, partly because secrecy is the essence in this field. So the old Cold War deterrence, when both the US and the Soviet Union knew that they had the ability to destroy each other with nuclear weapons and knew what these weapons were, is irrelevant today.

Still, this does not mean that Washington has no options to retaliate, or no ability to make it clear to Russia, China or any other power intent on penetrating US information systems that it would have to pay a heavy price for such efforts.

CYBER RETALIATION

The first weapon which the US possesses is its sheer technological advantage and potential, both of which act as deterrence in themselves, simply because any country which decides to corner the US in this area knows that it would ultimately be hard-pressed to prevail.

President Barack Obama has already used this "soft deterrence" effect to persuade the Chinese leadership not to push the US into a cyber arms race. China, Mr Obama told Beijing's leaders, "could choose to make this an area of competition, but I guarantee you we'll win if we have to". Of course, China never admitted that it took this threat seriously. But Chinese cyber intrusions have become more selective of late, perhaps because decision-makers in Beijing instinctively know that provoking the US on this matter is a fool's game.

And although Cold War-style deterrence does not work in the cyber age, some elements of old deterrence theory are still applicable. One such element is what Cold War specialists used to call "horizontal deterrence", the strategy by which the response to an act of aggression does not need to be with the same weapons or in the same way used by the aggressor.

So, if the US wishes to respond to Russia's intrusions, it does not need to do so by penetrating the Kremlin's computers, or by paralysing some Russian network.

It could inflict similar damage by, say, releasing intelligence information about the Russian leadership's financial affairs or the foreign locations where their money is stashed away, the sort of information which will hurt Russian government members just as much. In short, the best retaliation to a cyber offensive is often not in the cyber domain at all.

What is certain, however, is that the US can no longer sit idly by and ignore the latest Russian cyber operation. Some move against Russia is imminent. Every intelligence specialist around the world will be watching carefully what that move may be. And, as advertisers love to say: "Expect the unexpected."