According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in 2016 we are witness to the highest levels of forced displacement in modern history. An unprecedented 65.3 million people globally were displaced at the end of last year, compared to 59.5 million just 12 months earlier. People flee their countries for a variety of reasons including war, political persecution, religious persecution and other human rights abuses. Some people flee to neighbouring countries and some flee to the opposite corner of the globe. Some end up here in South-east Asia.

In Asean, only Cambodia and the Philippines have signed and ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention, and/or its 1967 Protocol. These two instruments not only provide the definition of who a refugee is, but also the core rights to which they should be entitled. This includes not sending a person back to a country where their life may be in danger.

In the majority of countries within Asean, refugees are treated under the Immigration Act of that country, with no distinction between someone seeking protection and any other ordinary migrant. This leaves the vast majority of refugees and asylum- seekers vulnerable to exploitation, unable to access adequate healthcare and at risk of arrest or indefinite immigration detention.

A notable exception within Asean is the Philippines, where refugees have access to visas and livelihoods. Last September, the Department of Justice extended this to include the right to travel, work and study. It also provided some measures for the prevention of statelessness. Such actions should be seen as a positive model which other countries in the region can emulate.

In South-east Asia, there are about 9,000 registered urban refugees in Thailand, 14,000 in Indonesia and 150,000 in Malaysia.

In each of these three countries, governments use immigration detention as a means to curb irregular migration and as a deterrent to more arrivals.

However, international research shows that this does not deter people fleeing for safety. There is no distinction made in each of the three countries' laws between refugees needing safety and sanctuary, and others who have simply overstayed their visa and are able to return safely to their home country.

HOW THEY ARRIVE

Most refugees generally arrive in South-east Asia on tourist visas, a relatively simple, inexpensive and quick category of visa to attain.

However, after arrival, it is nearly impossible to renew. They soon lose their immigration status and become "illegal" under the immigration laws of their host country. Many end up in immigration detention, often for years.

Oscar (name has been changed), a UNHCR-recognised refugee, spent a total of 14 months in detention in Thailand. He describes his time there as characterised by poor hygiene, overcrowded cells, corrupt guards, inadequate nutrition and systematic violence and brutality. Healthcare provision was also said to be grossly inadequate, and access to support for mental health conditions was completely absent.

On being released into the community after posting bail (this programme is currently suspended), Oscar described himself as "a broken man, left with a lifelong psychological scar to heal".

Unfortunately, the issue of immigration detention is not restricted to South-east Asia, but is one that refugees face in many countries across the region.

Australia, Japan, Korea, Pakistan and Sri Lanka all use immigration detention to varying degrees.

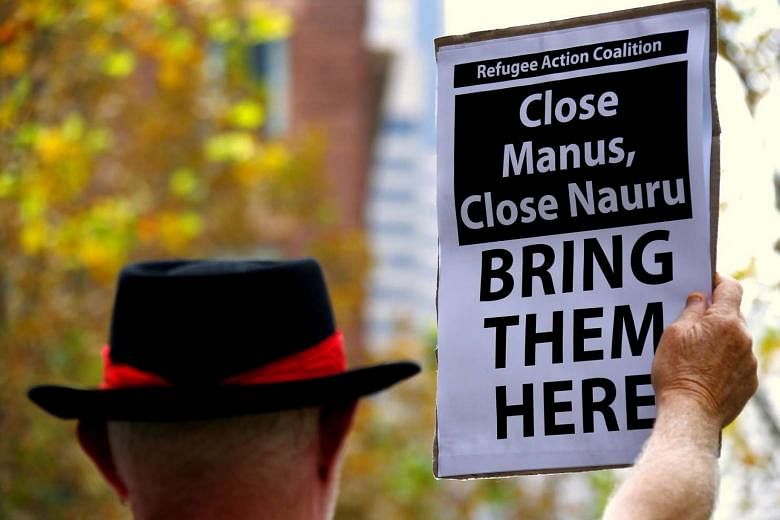

Most infamously, Australia goes so far as to detain asylum-seekers and refugees in offshore processing centres on Nauru and Manus Island. These facilities have been condemned by human rights groups as inflicting psychological distress and developmental damage on this vulnerable cohort.

We live in an era of increased fear and insecurity, with many governments espousing the virtues of immigration detention as a tool to ensure peace and stability and to safeguard their borders.

However, immigration detention must not be used as a first resort. There are numerous alternatives, as evidenced by government policy around the world that shows that it is not the answer. It is not a place where individuals and families should be locked up. It is not a place for people fleeing persecution. It is not a place for children.

Governments across the region need to seriously rethink how they approach refugees, seeing them as an opportunity, not a burden. They must also acknowledge that immigration detention does not deter people from travelling to another country. When your life is in danger, you will travel to any place where you are safe.

In November last year, the governments of Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, in addition to civil society representatives and experts from across the region, came together at a Regional Roundtable on Ending the Immigration Detention of Children. This platform provided a space for participants to share positive practices from the region and beyond, and develop a strategy for a way forward.

In each of the three countries, there was a tacit agreement that children should not be detained, regardless of their immigration status. Despite this, there is still a clear disjoint between rhetoric and practice.

Governments across the region should take active steps towards ceasing the practice of immigration detention for refugees and asylum-seekers. There are numerous tools in the public domain that outline alternatives to detention that are more humane, more cost effective and more effective in migration management. These include: shelters for unaccompanied minors, community accommodation, periodic reporting and screening/assessment for vulnerable persons.

With a plethora of vibrant and willing civil society organisations able to assist governments, it is hoped that the two groups can come together to phase out this damaging practice.

In the words of one refugee who has subsequently been resettled in the United States, "life is not easy in detention. Every day I just think and think and think. I am not a criminal. I just want freedom".

- The writer is a programme officer at the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network based in Bangkok, Thailand.

- S.E.A. View is a weekly column on South-east Asian affairs.