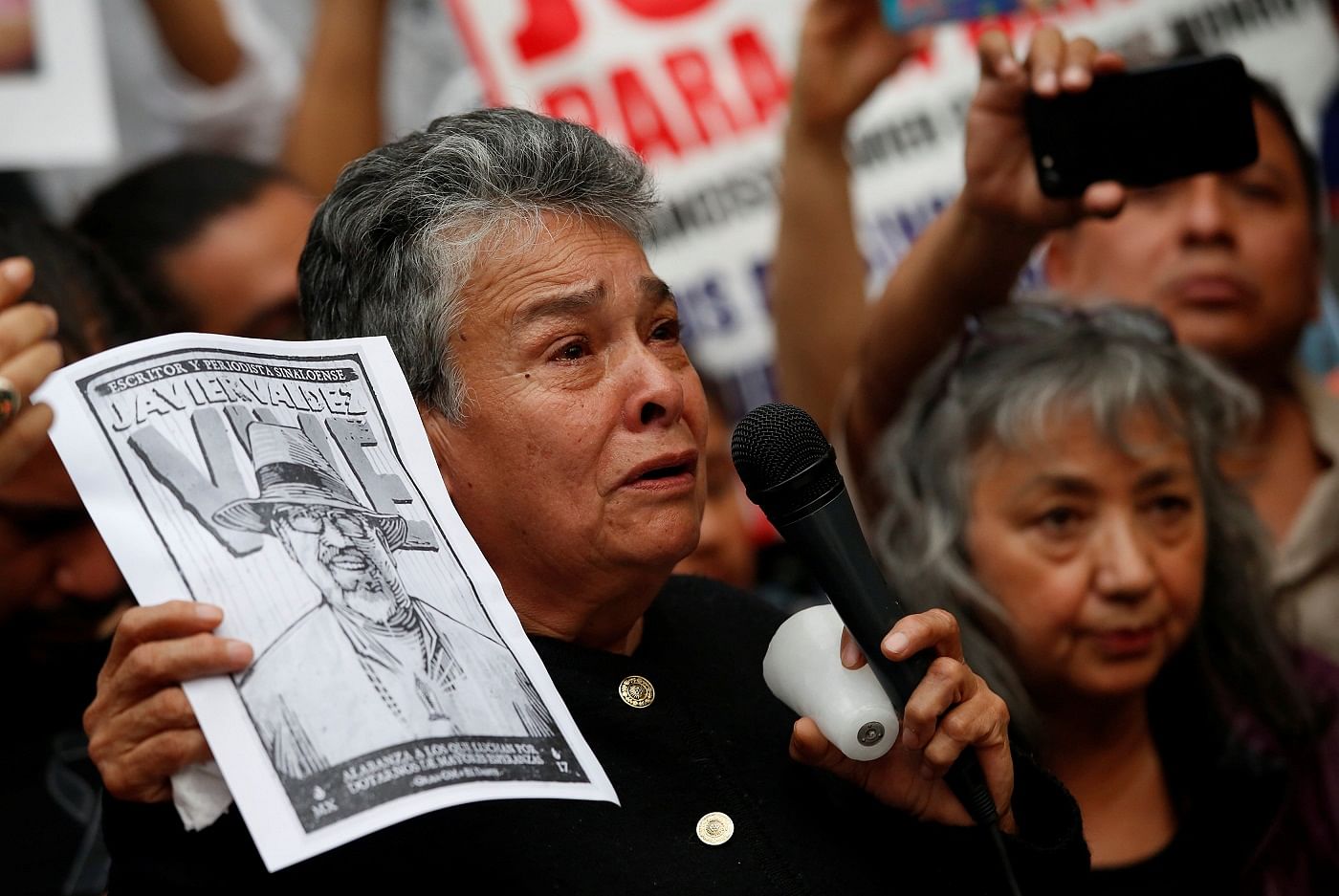

Daphne Caruana Galizia, Malta. Gauri Lankesh, India. Javier Valdez, Mexico.

Three journalists who likely never met one another yet shared brief moments in the headlines in the last five months after they were murdered doing their jobs. Valdez, 50, gunned down in Mexico City. Lankesh, 55, shot and killed outside her home in Bangalore. Galizia, 53, blown up in her car in Malta.

Like nine out of 10 of the 930 journalists killed worldwide in the last decade, according to Unesco, their murders have not been resolved. As press freedom shrinks in countries like Mexico, Turkey, Russia, Brazil and India, dangers of violence to journalists are on the rise.

It's usually not foreign correspondents in hot spots, like America's James Foley, beheaded by ISIS three years ago in Syria. Ninety-three per cent of the journalists killed are local reporters, "offed" by criminal gangs or corrupt political officials for their in-depth reporting of local corruption. Some, like Lankesh, were thought to be targeted by extremists for their political commentaries.

The horror of the killings - and in far greater numbers, jailings - is matched only by the lack of accountability of the authorities in the places where they occur. While we might expect journalists to face danger in places like Afghanistan, Yemen or Iraq, countries like India and Guatemala stand out on Unesco's lists of most dangerous places.

All of this makes the belligerent rants of US President Donald Trump even more chilling. Often, violence and oppression against those seeking to tell the truth starts with tough words and propaganda from a rising political leader and quickly manifests into something worse. Citizens and other media who stand by can quickly be caught off guard by the speed with which this phenomenon develops, such as in Turkey, where more than 150 journalists currently languish in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's jails.

Yesterday was the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists, designated by the United Nations in 2013 to call attention to the rise in violence. So far this year, 30 journalists have been killed while doing their jobs, and 10 of those were murdered, said the Committee to Protect Journalists. Last year, 48 were killed, 18 of whom were murdered.

Lots of people get murdered, especially in countries where freedom is oppressed and political power is used to squelch dissent. Journalists are not out to create political movements, however. They seeks to find and tell truth, to hold governments accountable and shine a light on the darkness of corruption. When they are targeted, the public loses.

Yet journalists fail to elicit much public sympathy, and the competitive nature of our craft makes it difficult to band together to fight tyrants, criminals or oppression of any kind. Often, as in Turkey, it is too late before the world notices.

This must change.

In Russia, editor Dmitry Muratov of the popular newspaper Novaya Gazette, where investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya was killed in 2006, has begun arming his staff to protect themselves. This followed the stabbing of a Russian radio journalist, according to the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers.

That might be deemed necessary in Russia but, so far, it is still extreme for most countries. What we can do is start working better together to tell one another's stories, both courageous and tragic. And tell you, the public, what is happening to us - quite rapidly in some places - and why it is important to them. We are storytellers, after all.

We often wonder how a political party in Germany was able to dominate the public psyche during the years of the rise of Hitler. Part of it was to blame, then stifle, then oppress, then take over the local media. Journalists paid with their lives, and the world suffered.

Hemingway's line about bankruptcy occurring "gradually, then suddenly" is often applied now to any sort of dramatic change. As we pause to consider what is happening to journalists in many countries today, we might give a thought to where we are on that spectrum. Then the names Galizia, Lankesh and Valdez, and their stories, will not pass into history in vain.

• David Callaway is president of the World Editors Forum, CEO of TheStreet.com and former editor-in-chief of USA Today.