In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, governments in developed countries have been actively intervening in their economies to support growth. However, most of their policy tools (primarily proactive monetary policy) have not been manifestly effective.

The United States' economic growth performance has for many years remained lacklustre, even after successive interest rate cuts along with a few rounds of "quantitative easing" (the central bank injecting massive money supply into the economy by purchasing financial assets from banks).

The European Union and Japan, having taken to the even more extreme type of monetary policy with negative interest rates, have also achieved precious little. Particularly for Japan, its quantitative easing (Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's "First Arrow") has actually been a spectacular policy failure.

Against this backdrop, China's macroeconomic management policy does appear to have been successful, especially judged by its relatively high growth performance in that period. As the global crisis struck China, then Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao hastily put up a huge stimulus package of 4 trillion yuan (S$827 billion) - basically a combination of fiscal and monetary policies - to prop up economic growth.

In the event, China chalked up double-digit rates of growth for three years until 2012. But this led to a huge expansion of credit and loans, which in turn created a lot of excesses from over-investment and overproduction to a property bubble. As growth started to slow after 2012, it was also "payback time" for loans, with some turning "sour" to become non-performing loans.

Indeed, China's total debt rose to 260 per cent of gross domestic product now from 180 per cent in 2008. Given the country's high domestic savings and high foreign reserves, its debt situation should be manageable. But any debt problem still needs to be defused, as a large debt overhang is a drag on economic growth.

More specifically, over-investment and overproduction have since operated as impediments to China's economic growth. Huge overcapacity from steel to coal to cement have subsequently reduced the operational effectiveness of the government's pro-growth policy intervention. This explains why the government's demand-side stimulus package of six rounds of interest rate cuts and four rounds of reduction in reserve requirement ratio throughout last year failed to turn the economy around.

Thus, at the annual Central Economic Work Conference held last December, a number of policy measures were adopted to tackle the acute problems on the "supply side", such as deleveraging debt, reducing industrial overcapacity and closing down loss-making state-owned enterprises. The Chinese press hailed this new policy package as a kind of market-based "supply-side economics".

In his wide-ranging discussion of China's economy with provincial-level officials on Jan 18 this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared plainly that the most acute problems in the economy were on the supply side. He called for intensified efforts to carry out "supply-side reform".

As China's economic growth at the start of this year continued to be sluggish, economic policymakers from the State Council (China's "Economic Cabinet") headed by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang were under pressure to bolster growth, and they accordingly resorted again to demand-side stimulus measures. In the event, China's growth in the first quarter of this year was stabilised at a respectable 6.7 per cent, well on target.

However, such growth came from a large injection of credit and loans (officially, "total social finance") of 4.6 trillion yuan, or 40 per cent of last year's level. To Mr Xi, this was hardly a move towards deleveraging. Such demand-driven growth was achieved at the expense of slowing down his much-coveted supply-side reforms. To him, this was the straw that broke the camel's back.

DEMAND AND SUPPLY VERSUS DIRECT AND INDIRECT

What is demand- and supply-driven growth? Modern economics started with Adam Smith, whose masterpiece, The Wealth Of Nations, laid the foundation of classical economics. The work is actually about economic growth. The classical economic formula for growth ("production function") is focused mainly on the supply side, taking demand as given. The underlying assumption of classical economics is Say's law of markets, which argues that "supply creates its own demand".

In those early days of capitalism, the supply of the main factors of production, such as capital, land and technological progress, was indeed limited and constrained.

As the capitalist system in England got mature at the end of the 19th century, problems such as overproduction and under-consumption, business fluctuations and unemployment (classical economics also assumes full employment) started to emerge. These problems got worse after World War I, giving rise to the Great Depression of the 1930s, with unemployment in the US rising to 30 per cent - extremely serious as most families in those days had only one breadwinner working full-time.

Famous Cambridge economist John Maynard Keynes then identified the "lack of effective demand" as the major cause of existing economic woes.

Keynesian insights revolutionised macroeconomics, paving the way for government intervention to stimulate demand. That helped post-war developed capitalist economies to maintain two to three decades of strong growth and stability, based on governments' constant macroeconomic fine-tuning, along with some key built-in stabilisers.

Such macroeconomic intervention has come to be known as "Keynesian demand management". It usually consists of both monetary and fiscal policies.

The former involves variation in interest rates and money supply, while the latter depends on changes in taxation and government spending.

Whereas monetary policy operates with the market as an indirect policy instrument, fiscal policy often involves more direct government participation and is thus much more political in nature. In practice, monetary and fiscal policies often operate in tandem. Fiscal policy cannot work without altering money supply, while appropriate interest rates are crucial to the government spending programme.

In the 1970s, high inflation took hold in the US as the country could no longer afford to have both "gun and butter", that is, fighting the Vietnam War while undertaking then US President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society social spending. Inflation led to the rise of monetarism, with Milton Friedman of the University of Chicago as its key advocate. Obviously, it is more effective to tame inflation by controlling the money supply - "Without water, fish cannot live"!

The ideological underpinning of monetarism is politically highly conservative, as it also advocates more market and less government. This fit in well with the rise of the right-wing political thinking of the time, associated with former US president Ronald Reagan and former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher. The rise of monetarism thus spelt the demise of Keynesian demand management.

In fact, Mr Reagan, reacting against the inefficacy of demand management, advocated a kind of supply-side approach based on tax cuts and deregulation.

Central to his supply-side policy is the "Laffer curve", which shows a positive relationship between reducing tax rates and increasing tax revenue. The underlying rationale of supply-side policies is that they provide incentives for businesses to expand and for workers to improve their productivity.

The popular media dubbed Mr Reagan's policy prescriptions "Reaganomics", which, in a formal sense, is often known as supply-side economics, or the origin of it. Ironically, Mr Reagan's vice-president George Bush (the senior) later dismissed Reaganomics as "voodoo economics", saying Mr Reagan's tax cuts did not bring about a balanced budget to the US.

SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS, CHINESE-STYLE

In China, macroeconomic management by then Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji throughout the 1990s was called Hongguan Tiaokong (macroeconomic controls), which mixed administrative measures with market levers. It was basically a kind of demand management, relying heavily on fiscal policy, as China's monetary institutional structure was then not yet mature. The main thrust of Mr Wen's 2009 stimulus package was clearly also on fiscal policy. Unlike most developed economies, China had the ammunition to effectively operate fiscal policy because its government debt and fiscal deficits were relatively low.

However, the entire policy environment in China radically changed last year. With debt piling up and excess industrial capacities persisting, this was hardly fertile ground to run demand-side stimulus to prop up growth.

Hence, Mr Xi felt compelled to intervene, thereby revealing a high-level policy split on economic management in China.

On May 9 this year, the People's Daily ran a front-page interview report of an anonymous "authoritative figure", widely identified as Mr Xi himself.

Mr Xi was openly critical of the demand stimulus policy of the State Council under Mr Li, saying such debt-fuelled growth is unsustainable.

This time, Mr Xi made no bones about his preference for supply-side structural reforms. He is actually not fundamentally against the demand-driven growth strategy per se. To him, supply-side policies are more effective in addressing China's economic problems today.

What is even more remarkable is that Mr Xi had taken pains to clarify the difference between supply-side economics as understood in the West and the "supply-side policy" he has been advocating.

The former refers to the conservative economic policy characteristic of Reaganomics, while the latter is about the kind of policies targeting China's existing economic woes, ranging from excess industrial capacities to loss-making state enterprises. All these are measures, along with the promotion of innovation, deemed critical to future economic growth.

Overall, Mr Xi appears to have a better grasp of the theoretical structure of economics and its policy implications than Mr Li, who has a PhD in Marxian economics from Peking University.

"Xijonomics" also appears to be more relevant than "Likonomics" for the present state of China's economy.

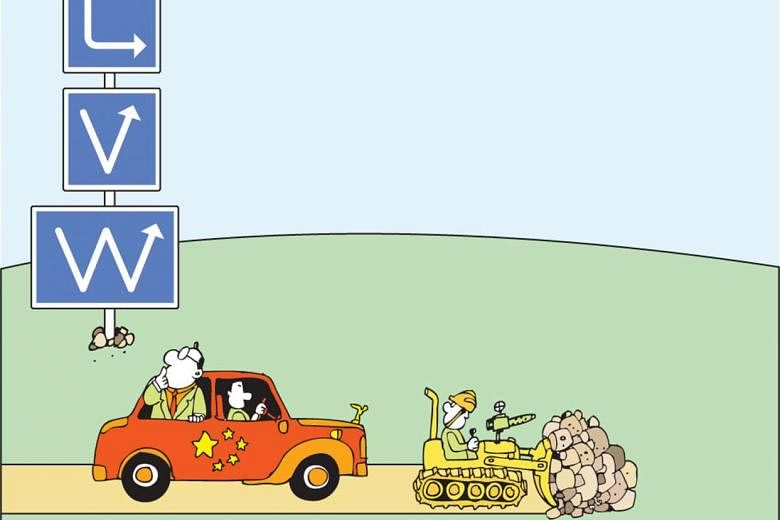

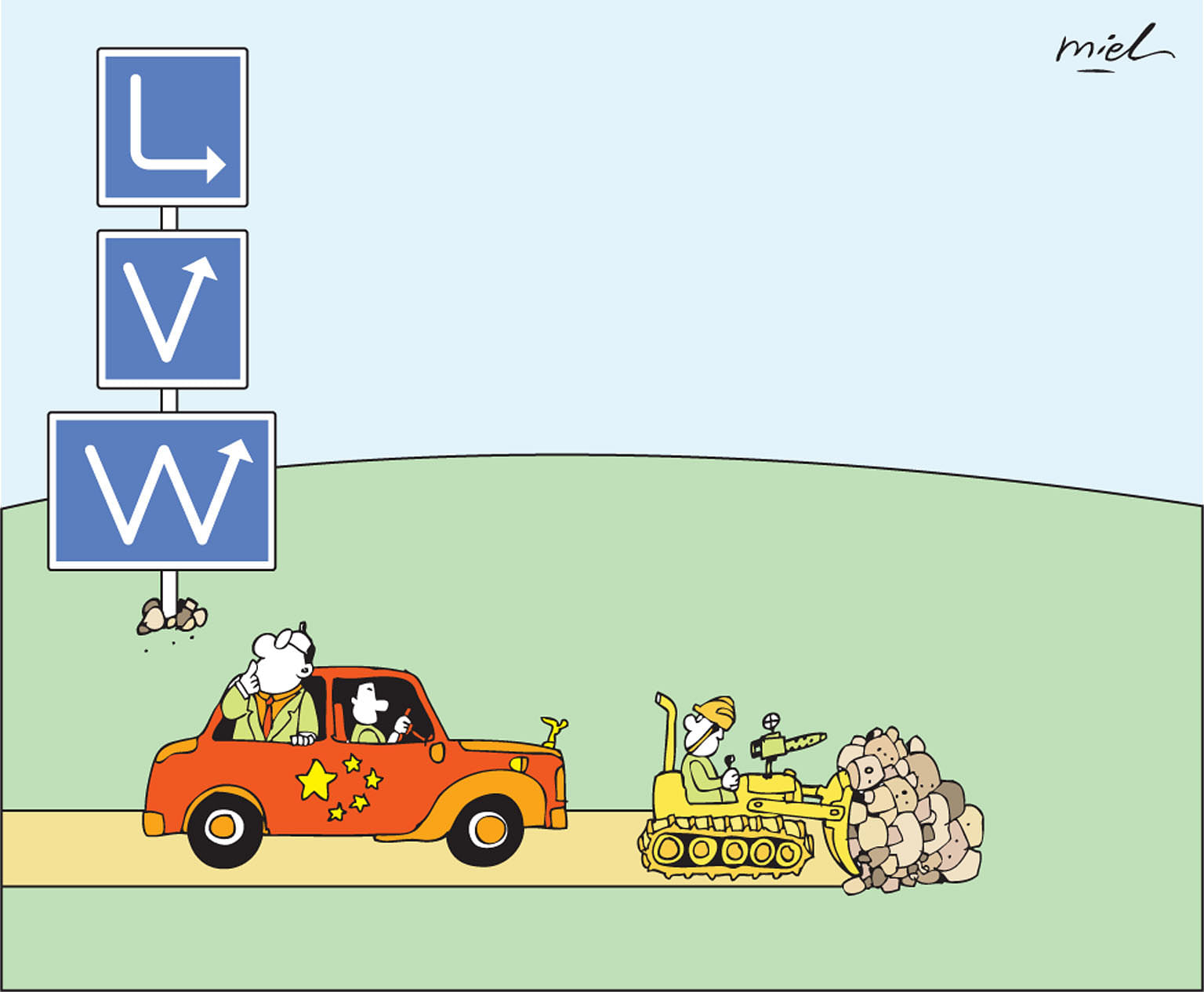

China's economic growth during the next phase of structural reforms is likely to be flat, in the "L-shape" trajectory rather than the "V-shape" or "W-shape" growth pattern, without short-term rebounds due to artificial demand stimulus.

Accordingly, China's economic slowdown is set to continue, with the economy growing at a narrow range of around 6.5 per cent. Whether future growth is trending up or down much depends on the actual outcome of the supply-side structural reforms.

The political ramifications of this episode are significant. The world has come to know that China is heading for a big shift in its economic strategy following the high-level policy split. Mr Xi has no doubt won the day, being able to play his "strongman politics".

However, the manner in which he has relentlessly pushed his views and forcefully seized the nation's major economic agenda must have diminished the State Council's traditional role in the nation's economic management. It has demoralised Mr Li and his team of economics ministers. It must have also undermined policy debates in the policymaking establishment.

The future direction of China's economic policy remains quite uncertain.

- The writer is a professorial fellow at the East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore.