In a country with no bars or clubs, young Iranians are hanging out in cafes and sipping coffee. But traditional teahouses, or chaikhanehs, are here to stay.

In a dimly lit shop in Julfa, Isfahan's popular Armenian quarter, young women and men sit next to each other, cups clinking, the smell of cigarette smoke lingers and Pink Floyd plays in the background. It looks like a bar, except there's no alcohol on the menu and the Farsi signage reads Cafe Van.

Pubs and clubs are forbidden in the Islamic republic - at least, publicly, as the young people would say - and so Iranians are turning to cafes as a modern alternative, which have become important places to socialise.

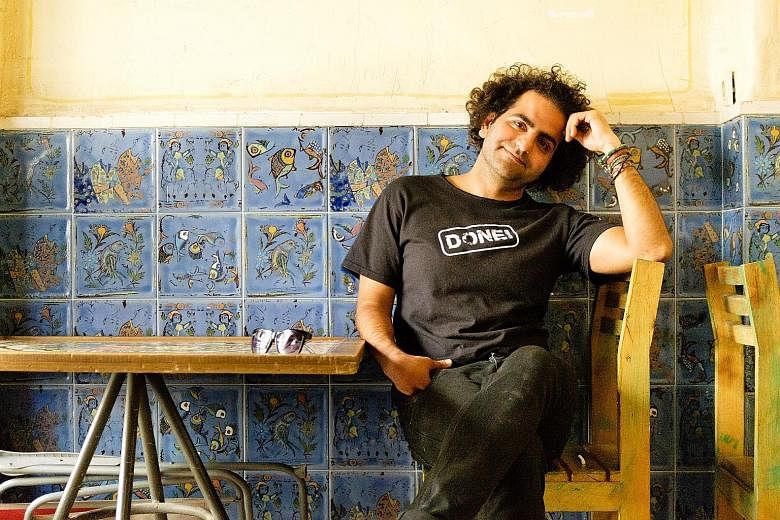

"In Iran, there are few places to hang out, so people go to cafes," said Mr Ali Bagheri, 30, the owner of Cafe Van.

"Mostly teenagers and couples come here. They pass their time, meet their friends, see each other. It's a safe space for them to communicate and interact," he added.

Mr Bagheri, who went to Austria when he was 16 to learn to become a barista, started Cafe Van five years ago, at a time when modern cafes were uncommon, he said.

Iran's traditional drink is tea and teahouses are a common sight.

But now, there are at least 100 cafes in Isfahan alone, up from about 10 four years ago - a growth fuelled by the changing taste and lifestyle of young Iranians, cafe owners said.

Mr Mehdi Tourgoli, 45, the owner of Sharbatkhane Baharnarenj Cafe in Julfa, said: "Young people prefer coffee because they sleep less now. They are working harder. The caffeine keeps them awake."

Iran's cafes, like any Western equivalent, serve mocha, cappuccino, latte and espresso. Displayed on the cafes' craft-paper menus are prices that typically range from 100,000 to 150,000 rials (S$4.50 to S$6.70) for a cup of hot coffee.

Drinking coffee started becoming a status symbol in Iran two years ago, Mr Bagheri said.

"Most Iranians want to show they are of a higher class by drinking coffee. Those who travelled overseas saw cafes, came back and now prefer to drink coffee," he added.

Inside the cafes, men and women mix freely. The women become relaxed with their dress code - the mandatory hijabs on the women's heads look like they could slide off any moment, hair flows out from the edges of the headscarves, exposing their ears.

For years, the Iranian authorities have raided cafes and threatened to shut them down as cafes were seen as symbols of Western influence and places that spread un-Islamic behaviour. The country has laws that prohibit unmarried, unrelated women and men from interacting in public.

According to Mr Mojtaba Khabbaz, 33, the owner of Ferdowsi Cafe in Shiraz, the issue of male and female interaction has always been a complicated problem in Iran.

"A month ago, late one night, I was going to say goodbye to the people in the cafe. I hugged this girl and someone from the police came in to say, 'Oh, you're not allowed to hug the girl.'

"He had been watching and started complaining about (expletive)," said Mr Khabbaz.

"He said he was going to take us to the police station. But another man with him, in plain clothes, said if I paid some money, they would let me off," he added. "This is quite common in cafes."

Yet, cafe-goers who have heard similar stories are undeterred. Among them are unmarried sisters Parmiss and Tina Afshar, who are in their 30s.

"We don't care. Girls and boys together... (the morality police) don't like it when young people enjoy themselves. But they can't stop it," said one of the sisters, both of whom are engineers in Teheran.

Mr Bagheri agreed and expects that the government will eventually loosen its grip on cafes.

"The culture is changing. Our clothes, our appearances and our tastes are different from 10 or 20 years ago. The government cannot control it," he said.

While increasingly popular, coffee has not replaced tea as Iran's favourite drink. There is no sign of teahouses disappearing.

Some 5km north of Julfa, across the Zayandeh-rud River, Mr Gholam Hossein sits behind a counter at Azadegan Teahouse. In the kitchen, a kettle of hot tea, or chai, boils over a gas burner.

The 57-year-old owner of the century-old establishment, who inherited the family business from his father, is not worried about the boom in cafe culture. For him, chai is still the national drink in Iran.

"There's nothing bad about opening new cafes. But Iranians prefer drinking tea. It's more relaxing," said Mr Hossein, who added coffee to his menu recently to attract the young. The price of a cup of chai starts at 20,000 rials.

Located at the end of an alley near the north-eastern side of Imam Square, the teahouse is a cave of wonders. Every square inch of the walls and ceiling is covered in photographs, lamps and intriguing knick-knacks from as long as 400 years ago.

Traditional Iranian teahouses, or chaikhanehs, which have been in existence since the Persian empire in 550 BC, still retain their charm - especially among middle-aged men. Mr Hossein, who is also the head of the community of teahouse owners in Isfahan, said there are at least 500 teahouses in Isfahan - a number unchanged for about a decade.

"Most people go to a teahouse to relax with tea and a shisha pipe. That's Iranian culture. It is a pastime and an entertainment," he said.

Even though the shisha was cleared from teahouses two months ago as part of the government's anti-smoking campaign, regular customers still return. "The government was worried about the shisha's sanitary and health impact," Mr Hossein said. "They tried to ban the shisha close to 20 times before, but it always comes back."

In a corner of Azadegan Teahouse, Mr Hassan Tajadod sits alone. Instead of a shisha, he lights a cigarette.

"I have to start my day with a cup of chai," said the 38-year-old tile painter, who has been going to the teahouse almost every day for close to a decade.

"Coffee? It's a drink for the upper class," Mr Tajadod said with a laugh. "I'm not used to the caffeine. It's not healthy for my heart. But tea, it's in our blood."

Pang Xue Qiang