LOS ANGELES • There is a certain allure, a Hollywood mystique, of becoming a major film or television production base. It should be no surprise then when national and local governments in South-east Asia explore the movie and TV industry as an added driver of job creation and economic growth.

Through the years, individual Asean member states have produced memorable film locations - if not yet an "Aseanwood" rival to Hollywood, or India's Bollywood.

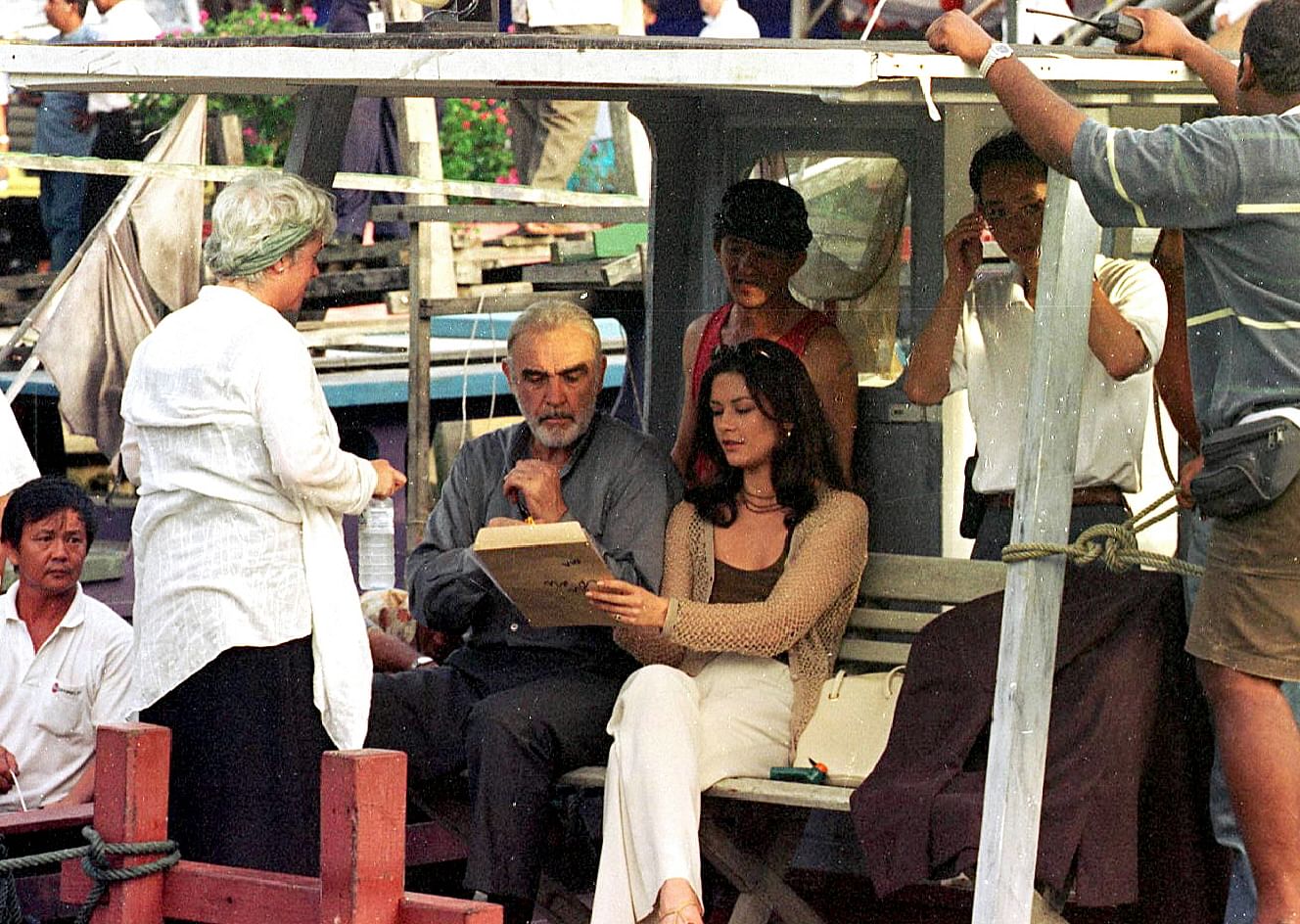

The Philippines filled in for Vietnam in Apocalypse Now, with its former president, Ferdinand Marcos, said to have offered military pilots and planes to help attract the Francis Ford Coppola production. Malaysia allowed filming at the then world's tallest buildings - the Petronas Towers - for Sean Connery's Entrapment.

Thailand and the Philippines have been among the most successful locations in Asean, with The Bourne Legacy and the Japanese heist film Lupin The Third filmed there in the past few years. Thailand saw James Bond visit in the 1970s in The Man With The Golden Gun and return in the 1990s in Tomorrow Never Dies - this time with Thailand playing the role of Vietnam.

Our work at the Milken Institute California Centre and the Milken Institute Asia Centre in Singapore makes clear, however, that before adopting tax incentives and other economic inducements to foster locally-based production, governments in South-east Asia must better understand the opportunity offered up by the film industry and its limits.

The money can sound tempting. By some counts, the film industry in the United States supports 1.9 million workers and US$47 billion (S$63 billion) in wages in the country alone.

In 2015, according to the Motion Picture Association of America, more than 330,000 local businesses benefited from the US film and TV industry. In Malaysia, according to Oxford Economics, the industry in 2013 contributed US$1.7 billion in GDP to the local economy and supported nearly 60,000 jobs. In Thailand, the industry in 2011 contributed US$2.16 billion in GDP and supported 86,600 jobs.

RIVAL ATTRACTIONS

For Asean, it is vital for any city, state or country seeking to become a centre of high-profile filmed entertainment to realise who they are competing against. An aspiring South-east Asian movie centre must compete against established American and British players, as well as neighbours in India, Japan, China and Hong Kong which already have established thriving domestic industries involved in all aspects, from pre- to post-production.

In some ways, South-east Asia also may aspire to follow the lead of South Korea, which has turned its local television productions into a major cultural and economic export.

But to produce a major domestic entertainment industry, one must draw upon significant amounts of local money, such as in China and South Korea, or be able to lure foreign productions to help build the local skill base of workers and bring interest to local productions.

Perhaps the best, new role models to have emerged closer to home are Australia and New Zealand. These Asia-Pacific nations have used newly built, multimillion-dollar studios and tax incentives to lure investment and work in films such as The Matrix and three Star Wars movies, as well as The Lord Of The Rings series, among others.

So, what should an aspiring Asean film hub consider before making the leap?

First, examine the state of existing film and television production facilities and consider the costs of investing in, and improving, such buildings.

When countries such as Romania and Hungary first started attracting movies, they did so by building on communist-era studios that were already in place.

Then, to continue drawing productions, they had to attract investment and interest in partnerships to upgrade.

In South-east Asia, Pinewood Iskandar Malaysia Studios is one example of a way forward, but even there, much of the investment came from within the country.

Second, maintain stability of any production incentives. Policymakers must recognise that actually building up a film or TV industry takes several years. Changing the terms of any tax or economic incentives for the weaker after only a few years can scare away productions.

Don't just throw money at movies. Economic incentives should be scaled to the number of productions that a local industry can support in five years' time. Any more than that and the local industry might be unable to provide enough local workers to take the jobs offered by new productions.

Third, train a local workforce. Chinese firms are doing this, bringing in foreigners to start up productions, with the idea of gradually transitioning to local workers. In Britain, a portion of film incentive money has been used to train what is now one of the world's most competitive film and TV workforces.

And fourth, be aware of the limits of your country's filming locations. A city such as Toronto, a major film production hub, can look like almost any major Western city in the world. A city such as Hanoi or Jakarta, however, may not do so as easily.

Importantly, it is not only the US motion picture and TV industry that is filming overseas. Chinese, Japanese and Indian companies do so as well. South-east Asian nations that want to be part of a growing, global film production industry must think ahead and plan and invest accordingly. This should include exploring opportunities for intra-Asean partnership. For an Aseanwood to emerge, an Asean country must commit for the long haul, and help its workers along the way.

Anything short of a long-term commitment is likely to meet the fate that many a Hollywood film seeks to avoid - a poor opening, fading revenues and a non-existent box-office impact that is quickly forgotten as the rest of the industry moves on.

• Curtis S. Chin, a former US ambassador to the Asian Development Bank, is managing director of advisory firm RiverPeak Group. Kevin Klowden is managing economist and executive director of the Milken Institute California Centre.

• S.E.A. View is a weekly column on South-east Asian affairs.