Over the past quarter century, the information technology revolution has transformed relations between people and between states, including in the conduct of warfare.

For the United States military, the manifestations of this revolution have covered the full spectrum from the dramatic to the prosaic. Unmanned aerial vehicles, ships and ground systems now carry increasingly sophisticated surveillance capabilities and precision guided weapons. Less visible, but also hugely important, has been development of the ability to integrate and analyse vast quantities of intelligence from all sources and determine precise locations of friendly and enemy elements. Finally, we cannot overlook growth of the seemingly matter-of-fact but nonetheless essential reliance on e-mail, video teleconferences and applications like PowerPoint to communicate, share information, plan and perform the tasks of command and control.

Information technologies that did not exist at the time of the first Gulf War are now so fundamental to military operations that it is difficult to imagine functioning without them. And the growth of the Internet, social media and now the Internet of Things represents a further stage in the information technology revolution whose full consequences are still unfolding. Nonetheless, some preliminary implications of such cyber capabilities for warfare are already clear.

First, cyberspace is itself now an entire new battlefield domain, adding to the existing domains of land, sea, air, subsea and space. This reality has enormous ramifications for military doctrine, operations, organisational structures, training, materiel, leadership development, personnel requirements and military facilities.

Most significantly, it adds a powerful new element to the challenges of the simultaneous "multi-domain warfare" in which we are already engaged and for which we need to do more to prepare in the future.

Second, cyber technology is adding another element to the already ongoing dispersion and fragmentation of global power. While no nation has contributed more to the growth of the Internet and the digitised world than the US (and no nation has developed more sophisticated cyber military capabilities), the nature of these technologies ultimately presents one more disruptive challenge to the preeminence that the US has enjoyed since the end of the Cold War, as others exploit the potential of offensive cyber capabilities in new and increasingly sophisticated and diabolical ways.

Examples of this include the use of cyberspace by extremist networks like the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria and Al-Qaeda to inspire far-flung terrorist strikes; by Russia to wage ideological and political warfare that seeks to undermine the cohesion and self-confidence of the Western democracies; and by China to collect the technological know-how that is speeding its already rapid rise and undercutting America's conventional military edge and industrial advantages.

Third, cyber capabilities are further blurring the boundaries between wartime and peacetime, and between civilian and military spaces. These are distinctions that have already been eroding and which technological developments are now accelerating. At present, it is clear that offensive capabilities are outstripping defensive and retaliatory options. And as long as difficulties in identifying and attributing responsibility for cyber attacks persist, that reality is likely to undercut deterrence and encourage aggression in cyberspace.

Yet even as technological changes inspire us to speculate on the future of warfare, perhaps the most important insights about the implications of the cyber age can be gleaned from the past.

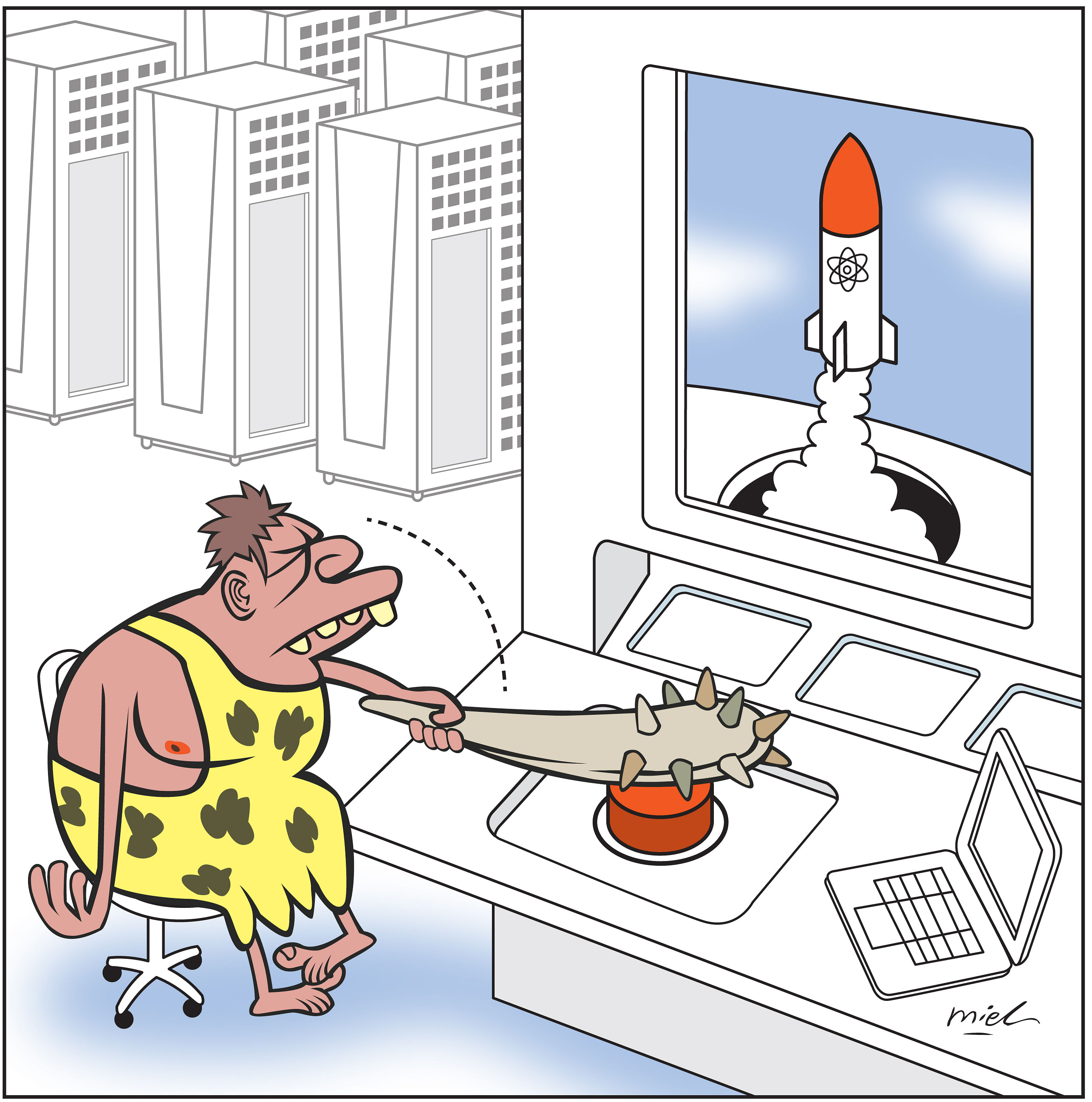

While technology promises to disrupt the conduct of war, it is equally important to recognise what it will not alter - namely, the causes of war, which continue to lie in the character of humanity.

As Thucydides documented more than two millennia ago, it is the elemental forces of fear, honour and interest that are the wellsprings of conflict, and it is often the choices of individual leaders that determine how conflicts develop. It was for this reason, in fact, that, when I was in uniform, I argued against the concept of "network-centric warfare" - put forward in the late 1990s - and instead contended that a better formulation would be "network-enabled, leadership-centric warfare".

It is, after all, still leaders who determine strategies and make the key decisions. And even as development of autonomous weapons systems and other such capabilities proceeds, parameters for actions by such systems will continue to be established by human beings.

Furthermore, history suggests that humanity's capacity for technical innovation often outpaces our strategic thinking and development of ethical norms. Indeed, the methodical development of doctrine around nuclear weapons by the "Wizards of Armageddon" in the 1950s and 1960s, which did much to help prevent a nuclear apocalypse, appears to have been the exception rather than the norm. More typical is the experience of the European powers of the early 20th century, which failed to recognise that the mass industrialised armies they were constructing were the components of a doomsday machine that would unleash a civilisational slaughter that none of the combatants had previously considered possible.

As the US and other major powers race to develop cutting-edge cyber capabilities - expanding swiftly into realms such as robotics, bioengineering and artificial intelligence - we would be wise to devote equal energy and attention to considering the full implications of our ingenuity. Security in the century ahead will depend more on our moral imagination - and with it, the ability to develop concepts of restraint - than it will on amazing technological breakthroughs.

This in turn suggests a final reality about warfare in the age of cyber. Regardless of the innovations that lie ahead, technology by itself will neither doom nor rescue the world. Responsibility for our fate, for better or worse, will remain stubbornly human.

ZOCALO PUBLIC SQUARE

•David Petraeus, a retired US Army general and former Central Intelligence Agency director, is chairman of the KKR Global Institute and a Judge Widney professor at the University of Southern California.

•The two essays on this page are part of an Inquiry, produced by the Berggruen Institute and Zocalo Public Square, on what war looks like in the cyber age.