When Singapore separated from Malaysia in August 1965, it continued to use a common currency with Malaysia and Brunei, the Malayan dollar. Issued by the Board of Commissioners of Currency of Malaya and British Borneo, the Malayan dollar was a currency that generations on both sides of the Causeway were accustomed to.

Independent Singapore had thus two options: continue with a common currency arrangement with Malaysia on a different basis, or issue its own currency.

Singapore preferred the common currency option, and began negotiations with Kuala Lumpur.

Despite their strained relations, the two governments agreed to discuss how the common currency arrangement could be preserved. We are able to trace the subsequent twists and turns of the negotiations from two sources. The first is the White Paper that the Singapore Government tabled before Parliament to explain what had transpired in the negotiations.

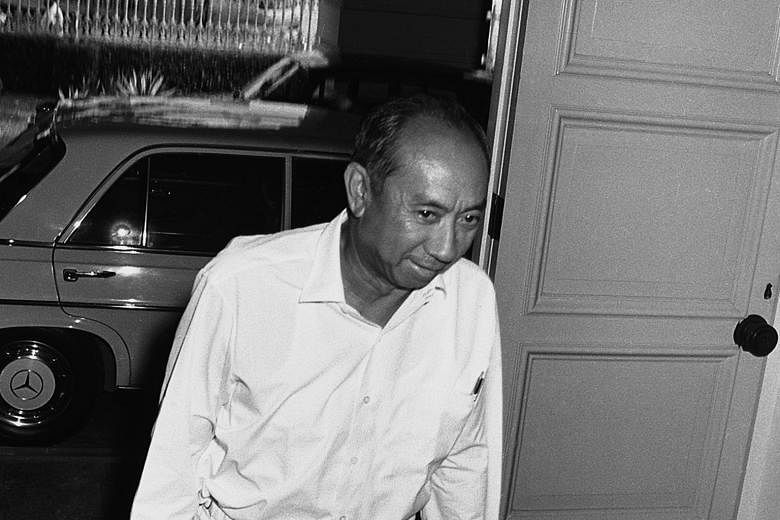

The other source is internal government files, which reveal the decisive role that Dr Goh (Keng Swee) played in shaping the thinking of his Cabinet colleagues, though currency issues were no longer part of his portfolio. He had moved from Finance to Defence in 1965 and took no part in the formal negotiations with Malaysia on the currency arrangements.

-

Story of reserves

-

This is an excerpt from a new e-book titled Safeguarding The Future - The Story Of How Singapore Has Managed Its Reserves And The Founding Of GIC.

It tells the story of Singapore's reserve management history, and recreates the vision, creativity and drive that led to the founding of GIC, Singapore's sovereign wealth fund.

The e-book was written by Freddy Orchard, GIC's former Economics & Strategy Department director. Readers can go to http://gichistory.gic.com. sg to download the interactive E-Book iPad App, alongside an ePub file, an illustrated PDF and an audio book.

The White Paper reveals that Singapore's Finance Minister Lim Kim San, as early as October 1965, just two months after Separation, had raised the matter of a common currency with his Malaysian counterpart, Tun Tan Siew Sin, who was also a cousin of Dr Goh.

On Nov 8, 1965, Mr Lim wrote to Mr Tan, recalling that both of them had agreed that "our two governments should do everything possible to maintain close economic and trade links between Singapore and Malaysia". He suggested one way to do so would be to continue with a currency board issuing a common currency. The other would be to establish a joint central bank that could then issue currency for both countries.

Mr Tan replied on Nov 13 to say that he had authorised the governor of Bank Negara, Tun Ismail Mohd Ali, to initiate discussions with Singapore. Indeed, Mr Ismail had visited Singapore a day earlier and had submitted a Memorandum on the Proposed Currency and Banking Arrangement to Singapore's Finance Minister.

Bank Negara's memorandum concluded that "economic and financial considerations would suggest that it would be to the mutual advantage of Singapore and Malaysia to continue to have a form of common currency and an integrated banking system". But Bank Negara rejected Singapore's first preference - a currency board.

Bank Negara also replied that a joint central bank was not acceptable, as it would involve "a passing of new legislation in Malaysia and a reconstitution of Bank Negara Malaysia". Bank Negara's suggestion was to continue the common currency arrangement, but with it issuing currency for both countries. There could be differences in design to differentiate the currency issued in Malaysia from the one issued in Singapore, though either one would be legal tender in the other. In the event, Bank Negara's proposal formed the basis of negotiations.

CONTROL OVER RESERVES

The other issue that Singapore raised concerned the control and ownership of the reserves - in the first instance, the pool of reserves transferred from the existing currency board. This, more than the type of monetary system, was a fundamental issue for Singapore: it would only agree to negotiations if there were binding assurances that its reserves would remain under its control and management. Bank Negara understood Singapore's concern and agreed to modify its original proposals concerning the arrangements for the management of reserves.

On May 9, 1966, Mr Lim wrote to Mr Ismail to say that Bank Negara's revised proposals, in particular the revision providing for separate physical control and management of the respective currency reserves, were acceptable in principle to Singapore. Negotiations could begin to settle matters of details such as the exchange rate parity, the design of the new currency, the appointment of the Singaporean deputy governor and the board of directors, and steps for liquidation in the event of termination.

Formal negotiations began on June 10. Bank Negara, the convener of the meeting, was represented by a team led by Mr Ismail himself, and included its deputy governor Choi Siew Hong and its Singapore branch manager Hooi Kam Sooi.

Singapore's delegation was headed by Mr Sim Kee Boon, then Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Finance, and included Mr Ngiam Tong Dow and Ms Elizabeth Sam from the Finance Ministry, Attorney-General Tan Boon Teik and Accountant-General Chua Kim Yeow.

The Malaysian government delegation was headed by Mr Abu Bakar Samad Mohd Noor, then Secretary to the Malaysian Treasury, Tan Sri Chong Hon Nyan and Datuk Malek Ali Merican from the Treasury, and Solicitor-General Salleh Abas. Two representatives from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) also attended the talks: U Tun Thin and U San Lin.

The delegations met 11 times in all, within a period of slightly less than a month. Each meeting was intense and gruelling. Some meetings would start in the morning and end after midnight. But though intense, the talks were civil. Mr Sim later remembered the negotiations as "difficult but not bitter". Mr Ismail, he said, "tried to be fair".

The personal ties among the negotiators helped. Mr Tan Boon Teik was from Penang. Mr Choi and Mr Hooi had studied at the University of Malaya in Singapore, which was also the alma mater of Mr Sim, Mr Ngiam and Ms Sam. Mr Sim had known Mr Ismail for some time and had developed a "cordial" working relationship with him.

The Singapore Cabinet was kept informed of the progress of the talks, with a small group comprising the Prime Minister, Mr Lim, Dr Goh and Mr E.W. Barker, then Minister of Law, monitoring events closely and sometimes meeting every day.

Dr Goh was then Defence Minister but was influential in shaping the Government's strategy in the currency talks. He took it on himself to compose detailed memorandums to explain to his Cabinet colleagues the complexities of monetary policy, the implications of the proposals being tabled and the stand Singapore should take. Mr Sim and Mr Ngiam found themselves reporting not only to Mr Lim Kim San but also to Dr Goh.

DYNAMICS BETWEEN GOH KENG SWEE AND LIM KIM SAN

Far from viewing Dr Goh's interventions as intrusions on his turf, Mr Lim welcomed them. Old friends from their days at Raffles College - Mr Lim had been best man at Dr Goh's wedding - they formed a formidable team: Dr Goh the economic theoretician and practitioner par excellence, and Mr Lim the businessman-turned-politician, a "political entrepreneur… who seized opportunities using powers of analysis, imagination, a sense of reality and character", as Mr Lee (Kuan Yew, the Prime Minister) was to describe him later.

We get a glimpse of how Dr Goh and Mr Lim related to each other from Mr Yong Pung How's recollections of his association with both men in the early 1980s, when Dr Goh was chairman of MAS (Monetary Authority of Singapore) and Mr Lim had been persuaded to come out of retirement to be the caretaker managing director of MAS. Mr Yong recalls the two having heated arguments over policy issues, the staff within hearing distance and cringing at the "unmentionable terms" they flung at each other. Then, wreathed in smiles, they would emerge for lunch, usually Peranakan food. But after lunch, back in the office, they would resume their heated altercations.

Significantly, Dr Goh seems to have been the most sceptical among his senior colleagues about the arrangements for the common currency. Dr Goh felt Singapore should seek two safeguards: First, each government's reserves should unambiguously be under its own direction. And second, Bank Negara should operate only as an agent of the Singapore Government, completely subject to the direction of the Singapore Finance Minister in matters affecting Singapore.

He forecast that these safeguards, though absolutely necessary for Singapore, would be unacceptable to Kuala Lumpur. Singapore should, therefore, be prepared for a breakdown in the negotiations, he advised.

Still, notwithstanding Dr Goh's reservations, and somewhat to his surprise, the talks progressed to the point of producing a final draft agreement. It provided for a common currency with the same design except that the Malaysian issue would be designated the "M" series and the Singapore issue the "S" series. The two issues would be legal tender in either country. Each country would control its own issue and the management of its reserves.

In a meeting with his colleagues on July 6, Mr Lee commented that Singapore did not get all the safeguards it had hoped for in the draft agreement. He observed that the proposed agreement was between two unequal parties, for Bank Negara was already an established institution while Singapore had no equivalent central banking machinery. The Prime Minister, however, viewed that the break-up of the common currency arrangement would forestall future wider economic cooperation between the two countries. The best option therefore was to accept the draft agreement and work towards modifying it over time.

SINGAPORE BRANCH 'NOT A LEGAL ENTITY'

A few days later, that decision was rendered moot. The trigger was a letter dated July 11 from Mr Ismail to Mr Sim on the status of a piece of land at Robinson Road in Singapore, the site of the proposed Singapore branch. The Malaysian view was that while the value of the land would be credited to the account of the Singapore branch, the title would remain in the name of Bank Negara Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur's position was that the Singapore branch was not a legal entity and could, therefore, not own assets.

This was a bombshell. If the Singapore branch could not own property, that would mean it could not be the legal owner of its reserves.

On July 15, Mr Sim wrote to Mr Ismail, pointing out that his position on the Singapore branch was at odds with the assurance that Singapore's "currency assets shall belong exclusively to Singapore". On July 21, Mr Lim informed Mr Ismail that he could not recommend to the Singapore Cabinet that it accept the draft agreement. In his reply, Mr Ismail reiterated Bank Negara's position that it could not countenance its Singapore branch being a legal entity separate from itself. The Singapore Cabinet was informed of these developments the same day.

Two days later, Mr Tan wrote to his Singaporean counterpart, noting Singapore's reservations about the draft agreement but also adding that a decision was needed by the end of July, as the deadline for placing orders with the London printers for the new currency notes was mid-August. On Aug 4, Mr Lim flew to Kuala Lumpur to meet Mr Tan at his residence, carrying with him a formal letter of reply.

The letter stated clearly that Singapore would never place its reserves in trust with an agency under the control of a foreign government. It suggested two options. One was to place these reserves with an independent trustee like the IMF or the Bank of England. The other was to incorporate the office of the deputy governor overseeing the Singapore branch as a Corporation Sole, and for Singapore's assets to be vested in him and not Bank Negara.

Mr Ismail replied that the Corporation Sole suggestion was unacceptable as it meant a separate legal entity, in effect a separate central bank. In a reply on Aug 8, Mr Tan also stated that Singapore's proposals were not acceptable. He subsequently visited Singapore on Aug 13. At a meeting at Rumah Persekutuan, he was given a letter by Mr Lim, which reiterated Singapore's stand that it could not be placed in a position where its reserves might be jeopardised. But Mr Lim expressed a willingness to explore "any alternative proposal" to resolve the impasse.

In a reply dated Aug 17, Mr Tan said the draft agreement did ensure that Singapore would have "the whole of the assets and liabilities shown in the books of Bank Negara Malaysia" in the event that the agreement was terminated. He added: "Your real fear is that we may not honour that agreement. The only answer to this is clearly to have no agreement at all."

And so it came to pass that at 1.30pm on Aug 17, 1966, both governments announced to their peoples that Singapore and Malaysia would have separate currencies from June 12, 1967.

Earlier, Dr Goh seemed to have been in the minority in thinking that a common currency arrangement was unworkable. In the end, the Cabinet was unanimous in deciding a complete currency break was preferable to risking Singapore's reserves. Ultimately, the talks failed because Singapore did not receive ironclad guarantees that it had indisputable rights over its reserves.

Mr Lim later explained in Parliament that he saw the issue of the ownership of reserves as a matter of national survival. Financial security was the cornerstone of a country's sovereignty, of a nation being the "master of its own fate", as he put it. He had lived through two periods when Singapore was under foreign rule - the British, and then the Japanese. Losing control over the reserves would be akin to exposing Singapore to the risk of being subjugated again, he felt.

Not for the first time, the Prime Minister was driven to conclude that there were limits to being conciliatory. He decided he would have been negligent if he had not insisted on the most watertight and stringent legal measures to ensure the safety of Singapore's assets. "Singapore's reserves," he wrote later in succinctly framing the issue on which the currency negotiations broke, "could not be protected simply by relying on trust".

Ultimately, despite the inevitable strain placed on the relationship between the two governments as a result of the failure of the currency negotiations, cooler heads did prevail. Mr Tan himself noted in the Malaysian Parliament that he could "appreciate Singapore's reluctance to enter into an agreement of this kind. Consequently, I suggest that this is not the time for mutual recrimination".

Subsequently, Malaysia and Singapore, together with Brunei, agreed to a Currency Interchangeability Agreement. The agreement allowed for the new Bruneian, Malaysian and Singapore currencies to be used as customary tender, fully interchangeable at par value, in all three countries. The agreement lasted till May 8, 1973.

In retrospect, it was clear that the Currency Interchangeability Agreement was but a stopgap measure to ensure that the traditional ties of banking, commerce and social intercourse between Malaysia and Singapore would not be abruptly disrupted by the currency split. Thus, despite the agreement, Singapore was confronted with stark economic realities even as it issued its own currency. The writing was on the wall: the destinies of the two economies would follow different paths. Singaporeans would have to find new ways of earning a living. The first separation had to be followed by a second.

It says much of the importance that Singapore's founding leaders accorded the country's reserves that they chose to face the existential uncertainties of a currency split rather than risk Singapore losing control of its reserves.

How Lee Kuan Yew grilled the GIC consulting team http://str.sg/4oUw.