As I walked down the stairs of Shophouse Hostel, I wondered at all I would encounter in the National Museum of Singapore on my first morning in the city-state.

Would it be a grey retelling of the country's history with the most colourful parts reserved for blood-red battles and insurrections? Would it simply mimic national museums from other global hubs of the world, describing the rise of the city-country in a way that was no different from the advancement of any other country that figured out how to proverbially procure gold from a swamp? Or would it take on a degree of authenticity it could truly call its own?

The questions drizzled around me in a flurry, one by one, causing a small puddle to form. I smiled and stepped over it, only to realise that outside, in the world that existed beyond my imagination, it was monsoon season.

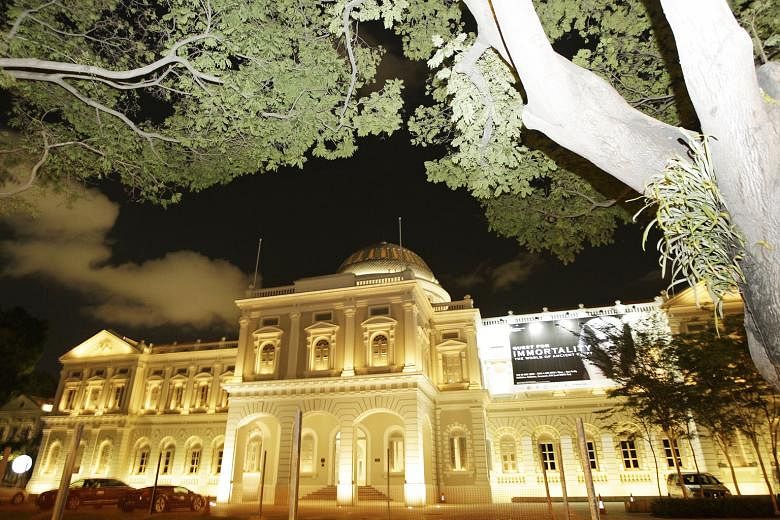

I hurried to the museum, which was a 20-minute walk from my hostel, purchased my ticket from the welcoming cashier and entered the gallery on the main floor.

It was then I realised what kind of museum I found myself in; not a domineering structure made of reinforced concrete, glass and steel, but a time machine. From the moment I set foot in the gallery, I was no longer in 2017 Singapore, but, instead, I was transported to the 14th century when it was known as the integral trading port of Temasek.

I made my way through the exhibit, reading about the attacks on the settlement and the coming of the Portuguese in the 1600s. I pressed on to the 1800s, which is when, with the arrival of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Singaporean history began to get real juicy.

Raffles was an Englishman who saw the value of Singapore and urged the British king to adopt Singapore as a crown colony. The only issue was that the Dutch also laid claim to the land, so Raffles, while he was instructed not to, did all he could to secure and consolidate power while not provoking armed conflicts. Long story short, Raffles was successful in establishing Singapore as a trading settlement in 1819 and, in 1824, as a formalised entity of the East India Company, which represented British interests.

It was over the next few decades that the colony, due to an influx of Chinese immigrants and Indian convicts (yes, convicts), grew to prominence and wealth riding on the coat-tails of demand for rubber and tin in the budding automotive industry.

The museum itself is laid out in a convenient and orderly fashion; like much of Singapore. It takes you through the history of the city-state, from ancient Singapura to its crown colony infancy to Syonan-to to the Singapore we know today. You can watch videos of men pulling rickshaws in the early 1900s (fun fact - rickshaws come from Japan, and the Japanese word, jinrikisha, means human- powered vehicle), learn how opium dens used to function for Chinese coolies (you basically learn how to smoke opium yourself), and view photos of the different classes of convicts brought over from India to build the city-country, and wonderful displays that show how the newly elected government managed to transform the literal landscape of the city-country, destroy unemployment, ensure every citizen had modern housing, move the city-state from a labour-based society to a skills-based society, and much more.

But, I'm getting ahead of myself. The title makes reference to tears, and tears were shed.

The first of the two tear-shedding experiences I had was when I walked through the halls of rooms dedicated to Syonan-to; the name the Japanese military gave to Singapore in 1942, which means "Light of the South". During World War II, the Japanese military defeated the mighty British and took over Singapore. They forced citizens to learn Japanese, starved many and did other heinous acts, one of which was Sook Ching, which means "purge through cleansing". What the Japanese military did was round up thousands of Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 and then massacre them. While the numbers are disputed, it could have been as high as 50,000 people; 50,000 individuals who woke up, went to work, ate dinner and slept like you and me. By this point in the exhibit, it was as if I were fully immersed in a movie that pulls you in and doesn't let go. But, reading about Sook Ching and seeing real belongings that were uncovered with the bodies at the mass graves snapped me out of the movie and showed me it was real. So real, in fact, that it became surreal.

All of the information I was receiving began to feel heavy in my head, hands and heart to the point that it became overwhelming. So, a few tears were shed.

With a heart made heavy from a side of the country's history I wasn't expecting, I moved on to a gallery that discussed the making of the Singapore we have today. After Singaporeans saw the British, who controlled them for over a century, fall to the Japanese, they wanted independence.

So, they achieved partial self-governance in 1955, and then merged with Malaysia in 1963. As I made my way through the room, I read of race riots, marches and heard the words of a man speaking, yet I didn't know who he was. I exited one room to find a man on a screen speaking in the next. He looked focused, optimistic and, despite wearing an expression of concern, his overall manner was relaxed and assured.

It was the same faceless man I heard speaking in the other room, only now I had a face to match the voice. I sat down on a bench in front of the video, and heard the man, who I came to know as Lee Kuan Yew, the first prime minister of Singapore, speak of the country breaking away from Malaysia. He spoke of a unified Singapore, where everyone would coexist regardless of "race, language, religion and culture".

To say I was both in awe and inspired would be an understatement. When I entered the room, I was about four minutes into the video, so I stayed to watch it again from the beginning.

Mr Lee opened by discussing why Singapore was breaking away from Malaysia. And, minutes in, his eyes began to moisten and his lips began to tremble. He expressed his deep sorrow over the decision, since he always saw Malaysia as a land that shared a kinship with his own.

And, by the end of the video, he says that he can no longer call himself a Malaysian, only a Singaporean, and expresses a fierce commitment to building a multiracial nation where all can thrive. A tear or two or three were shed.

I don't know if the 31/2 hours I spent in the museum were what caused me to become so emotionally wrapped up in it all, but I was.

I stood up from the bench and made my way through rooms dedicated to the industrialisation of the nation, and how the Government grew the country in more right ways than wrong.

A kitchen from the late 20th century was assembled with all of its anachronistic furnishings. Posters promoting two-children households were displayed; population control was never really something I've ever deeply considered, but it was eye-opening to see it promoted so much in the country 30 to 40 years ago as a means of stability. However, I hear now that the Government wants families to have more children, given that the population of the country is only around 5.5 million.

By the time I ran around the modern second-floor exhibits and pushed open the doors to the museum, causing a rush of heat and blinding light to envelop me, I had walked out with what I went in there for: information.

The country I stood in after visiting the museum was no longer the country I stood in before. I had a new-found, and deeply greater, appreciation for the people I saw running to and fro in the streets, the luxury cars stopped at red lights and architectural wonders that dotted the Lion City.

And while I knew, even then, that not everything in the country was perfect, I was in a better position to understand it all, despite being an outsider to a country I honestly never considered visiting before.

I suppose that's the nature of information; once you succeed in gaining hold of it, there's not much you can do to guard against it changing you, the way you see the world and the actions you take.

- Mateo Askaripour is a writer in New York who has worked on an orphanage in Nairobi and helped build a new university in Abu Dhabi. He is writing his second novel.