Just what is there to celebrate about Singapore's tripartism?

From one vantage point, a lot. The resident employment rate is at a record high of 72.3 per cent. Unemployment is low. Young people leaving school have good jobs. Companies feel secure enough to sink in billions in investment for the long term. Strikes are alien.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong delivered a suitably rallying speech at the May Day Rally on Friday, when he said of the National Trades Union Congress: "No trade union congress anywhere else in the world has been as effective as NTUC in improving workers' lives."

Even without raw data to substantiate that, I guess many will appreciate the sentiment behind that statement, which is that the harmonious state of industrial relations here is due to the hard work of unions, employer groups and the Government, and something valuable to be safeguarded.

But consider the challenges workers face today, and you might say tripartism still has a long way to go.

Income inequality has been on the rise. Median wages have not performed particularly well, having fallen, or stagnated until recently, and started modest growth only in the last few years.

In a candid analysis of Singapore's economy from 2004 to 2013, Professor Tan Kong Yam wrote in The Straits Times' Opinion section last August that the wage share of gross domestic product (GDP) fell from 45 per cent in 2001 to 39 per cent in 2007. He also said: "Over the 2002-2011 period, unit labour costs in the manufacturing sector declined by an annual average rate of 3.2 per cent, leading to substantial improvement in international competitiveness at the expense of labour returns. Wage growth was significantly below even the modest growth in productivity."

He did go on to say that changes in policy after 2011 have helped raise wages. Ministry of Manpower data show that real median income grew 1.9 per cent a year from 2009 to last year.

Meanwhile, anecdotal stories abound: middle-aged professionals who can't find decent jobs; and older Singaporeans who have to work as cleaners or security guards because they couldn't save enough to retire on, even after a lifetime of paid work.

The overall picture of Singapore's labour situation is decidedly more mixed than an aggregate look that focuses on our low unemployment figures and soaring GDP per capita would suggest.

Some self-reflection is in order this Labour Day weekend.

Yes, we have cause to celebrate Singapore's remarkable achievement of turning an industrial strife-torn society (26,600 man-days lost as a result of trade disputes in 1959) into a law-abiding, hard-working haven for investors.

But is our system so perfect and is Singapore so advanced in its industrial relations model that we cannot improve on it and learn from others?

The answer is clearly "no".

For one thing, Singapore's model of tripartism - of cohesive, not confrontational collective bargaining; and having tripartite dialogue on major issues - is hardly unique.

From the 19th century, in the wake of excesses of the Industrial Revolution, European societies like Germany and France have favoured the concept of "social partners" - formal, institutionalised networks of workers' representatives and employers' representatives who work with governments on labour issues. To be sure, they don't have a Cabinet minister as labour chief the way Singapore does.

But these partners meet the government for "social dialogue" to discuss and agree on broad parameters of policies on wages, jobs and and work conditions. In some countries, social partners go beyond dialogue and have a seat at the decision-making table. Social partnerships are so important, they are written into European Union founding treaties.

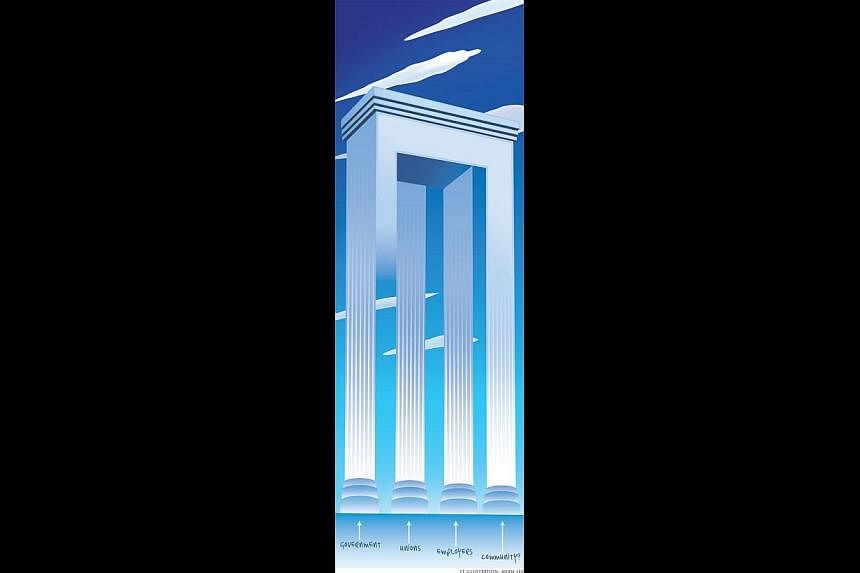

In countries like Ireland, social partnerships have expanded beyond tripartite groups (worker, employer, state) to include a fourth pillar - the community and voluntary pillar. This includes the unemployed, and those experiencing poverty and inequality.

That might be one thing we can learn from.

Another area that bears studying, and which indeed Singapore is embarking on, is in sectoral tripartism. Social dialogue at the sectoral level is a common feature of industrial relations in many countries in Europe.

In Singapore, we tend to focus on the ills in Europe: its high youth unemployment; its rigid labour practices; its welfare system sending governments into deficit.

But of course, Europe isn't all bad news. An interesting study by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions in 2012 looked at the role of social partners in addressing the global economic crisis. In some countries, sectoral social dialogue resulted in action to protect jobs: "In the food sector in Finland a collective agreement was signed in May 2010 to maintain workers' purchasing power in return for greater working time flexibility." That could mean higher per-hour wages, in exchange for flexi-work and shorter work hours.

In the Dutch construction sector, social dialogue during the crisis led to the creation of "anti-cyclical training programme" - employers train in bust times, so there are enough skilled workers in boom times, a good strategy for a notoriously cyclical sector.

In the metalworking sector in France, a national sectoral agreement on emergency measures to deal with the financial crisis was signed in May 2009. It emphasised skills training and improving qualifications to aid companies when the economy recovered.

These all sound like Singapore's approach, encouraging companies to send workers for training to save jobs during downturns.

Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam said that Singapore's new SkillsFuture initiative on lifelong training will take a sectoral approach. Sectoral committees consisting of industry associations, workers' groups, and the Government are being formed.

This is an important and welcome shift. A sectoral approach makes sense for Singapore's varied "two track" economy, which has labour-intensive, low-wage construction and cleaning sectors alongside low-labour, high-tech sectors like pharmaceuticals, and high-wage financial services. Issues from wages, productivity, and training, will be very different from sector to sector.

Rather than assume that Singapore is already at the peak of social and industrial policy, I hope the Government and social partners here have the curiosity and humility to look beyond cultural stereotypes, to study how societies older than our own have maintained social cohesion while increasing living standards through the centuries.