A new form of warfare is emerging, one that transcends the need to commit men and machinery to the battlefield, but which has just as much impact.

Tables were turned in global conflicts by the Dresden firebombing, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima and, more recently, the high-tech rain of ordnance characterised as "shock and awe" in the last Gulf War.

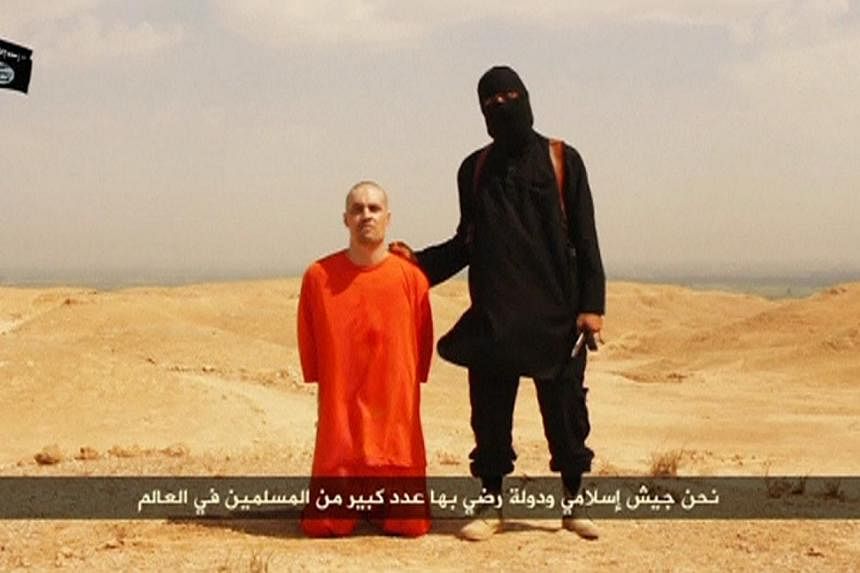

But nothing has been quite as proportionally efficient an act of war than the brutal decapitation of a hapless American reporter called James Foley by a lone masked jihadi speaking English and using a short blade on a forlorn patch of desert somewhere in Iraq.

Talk about shock and awe: Western political leaders scrambled to respond, some calling off summer holidays amid the clamour for firm retaliatory action. Unspeakably brutal as it was, this single act of violence has tipped the scales in a new and unexpected war the West is waging against the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which occupies ribbon-like slithers of territory across eastern Syria and western Iraq.

Reluctant to commit ground troops against a well-funded and well-equipped foe that takes no prisoners and imposes mediaeval Islamic law wherever it gains territory, Western countries are struggling to come up with an effective response to turn the tide.

Most worryingly, the ranks of this sudden adversary are swelling with recruits coming from the very bosom of developed Western society, which is supposed to be a bulwark against intolerance and extremism. Helped by pervasive social media and slickly produced promotional videos, ISIS has drawn as many as 2,000 foreigners into the fight.

The British government estimates that one in four of the foreigners fighting for ISIS is from the United Kingdom. That is almost more than the 600 Muslims currently serving in the British Army.

Implicit in the previous decade of struggle against Islamic extremism that focused on Al-Qaeda was the assumption of an unbridgeable divide between the brusque, bearded men of the desert hunkering in caves to avoid bombs or drones, and the civilised West guarding against further attacks using invasive, and sometimes illegal, security measures. These bearded men, mostly misfits and outcasts from their own societies, effectively assailed the West by flying jetliners into New York's World Trade Centre, killing thousands.

It took many years before the ringleaders were captured and killed. But it was asymmetric warfare by any measure.

No longer. Today's ISIS recruits are well-educated, middle-class sons of Muslim immigrants.

One was a supervisor at the British discount clothing retailer Primark, another an ace medical student. Two sisters who ran away from home in Greater Manchester to marry ISIS fighters in Syria had exemplary school grades. Well-spoken Reeyad Khan from Cardiff in Wales appeared in a recruitment video urging Muslim youth in the UK to join the struggle in Syam (the quranic name for Syria), "which is just and for Allah!".

Given this appeal and the apparent ease with which the ranks of foreign fighters are swelling, how will this war be won? What on earth will it take to resolve the underlying conflict between the West and this angry Muslim cohort?

Bombing has done little more than enrage the militants and fuel the pipeline of fresh recruits.

Nor is the struggle any longer about overthrowing the tyranny of Mr Bashar al-Assad's rule in Syria; it is more about imposing a mediaeval Islamic world view and driving out or killing all non-Sunni Muslims.

The script appears to be borrowed from some later Al-Qaeda thinking about the potential for establishing a caliphate in Syria, but has far exceeded dreamy notions of a theological state, and morphed into a totalitarian monster fuelled by untrammelled violence and brutality, which in turn appeals to the alienated youth from recession-hit Europe who have lost all hope and have long suffered discrimination and prejudice, as well as chronic unemployment.

All this suggests that the conventional prescription, the old shock and awe "bomb them to perdition" approach, won't work. In the longer term, what is needed is a twin-pronged approach to resolving this conflict, which has generated palpable fears of it spilling over into the streets of European capitals.

First, the West needs to disengage and step back from the morass of state disintegration in the Middle East, which is partly of its making: ISIS established a beachhead in Syria on the back of the civil war in which Western governments supported the rebellion against Mr Assad, thus helping to undermine a strong secular state. Equally, angry sentiment among young Muslims susceptible to ISIS recruiters has grown on the back of perceptions that the West has not done enough to support democracy in the Middle East.

Second, a greater effort must be made to ensure a better understanding of what alienates Muslim youth, and effectively address issues of self-esteem that have driven young men and women with prospects to serve as cannon fodder in Syria and Iraq.

This is not about patronising campaigns to deter radicalisation, but tackling the root causes of prejudice and feelings of cultural inadequacy and disrespect within multicultural communities.

In short, the West must wean itself off idealistic adventurism in the Middle East, and devote more care and attention to the health of its own plural societies. To do otherwise is to court defeat in a war waged so effectively with a camera, some slick editing, a short knife and a helpless hostage as victim.

The writer, who lives in Singapore, is the Asia regional director of the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, a Geneva-based peacemaking organisation.