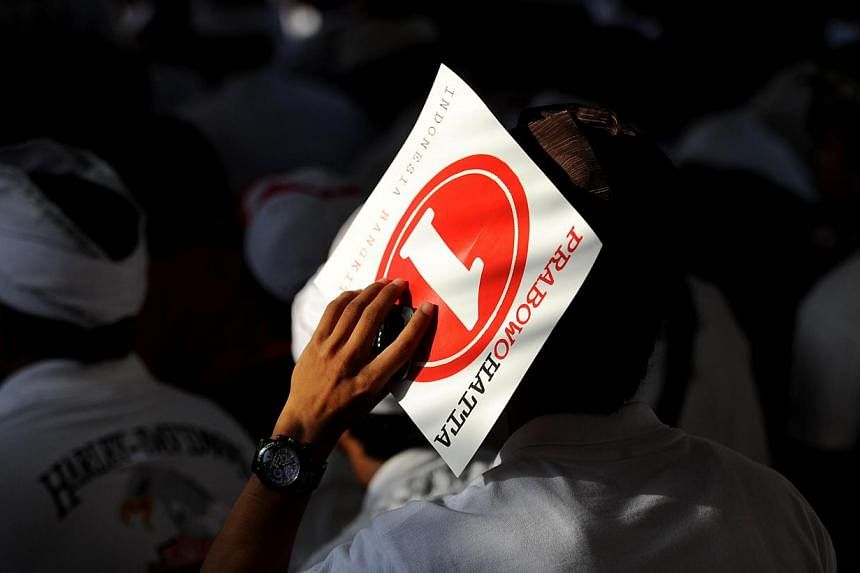

Recent reports that an Indonesian army officer allegedly attempted to persuade civilians in Central Jakarta to vote for former special forces commander Prabowo Subianto in the July 9 presidential election has highlighted some unfinished business in Indonesia's reform process.

By law, the Indonesian Armed Forces cannot be involved in politics. Soldiers are also barred from voting. But if anyone deserves to vote in an election, it is the soldiers who put their lives on the line to preserve national security and to secure the basic freedoms that are supposed to go with a democratic system. They have more right than anyone else.

Don't tell that to Indonesia, though. Indonesian service members were looking forward to taking advantage of a small chink in the door that would have allowed them to vote in the presidential election.

But even that has been denied them, with the Constitutional Court recently ruling in a judicial review that an article in the 2008 Presidential Election Law, only preventing them from voting in the 2009 presidential election, should not be allowed to stand.

Brought by former National Commission on Human Rights chairman Ifdhal Kasim and Institute for Constitutional Democracy lawyer Supriyadi Eddyono, the request for a review fell back on old arguments and ignored how much Indonesia has changed.

The plaintiffs asserted that the 2008 legislation failed to provide legal certainty on the issue, unlike the 2012 Legislative Election Law, which specifically bans men and women in uniform from voting - a practice dating back to a more turbulent period in the 1950s.

The court ruled that there should be no exceptions to the rule when the two national institutions had such important strategic roles to play. That meant their neutrality in politics must be guaranteed. It also supported the Justice Ministry's contention that the prohibition was all the more crucial given the fact that a growing number of retired generals, including presidential contender Prabowo Subianto, were now involved in politics.

Inherent in that is the argument that with more presidential candidates and political party leaders coming from the ranks of military and police retirees, it could lead to internal conflicts within the armed forces.

I don't buy it. The only obvious internal conflicts are between retired generals, such as Mr Prabowo and many of his superior officers from the days when he was Suharto's son-in-law and an ambitious rising star who rode roughshod over authority.

Serving officers may show deference to their so-called "seniors", but that doesn't go as far as slavishly doing their bidding. Once out of the chain of command, a general's power dissipates rapidly.

The incident in Central Jakarta involving an infantry captain canvassing for Mr Prabowo has all the hallmarks of an isolated incident.

In any event, Indonesia's one million or so soldiers and policemen won't make an iota of difference to the outcome of an election in a 180-million-strong electorate. In fact, voting collectively, they translate into just three seats in the 560-seat Parliament.

Nor does the security apparatus enjoy anywhere near the influence it once had. The same applies to even village heads and religious leaders. With a few exceptions, all that changed with the collapse of Suharto's New Order regime.

"Traditionally, the military has relinquished its voting right in order to claim political privileges that far exceed the weight of its actual votes," notes political scientist Marcus Meitzner. "This practice should be abolished in order to advance the normalisation of civil-military relations."

Critics say the military must fully reform before it is given the right to vote. Advocates believe voting rights would actually accelerate that process and allow security institutions to better integrate into civilian society.

"The armed forces as an institution is not allowed to participate in practical politics... but that doesn't mean we prevent individual personnel from voting," Habibie Centre researcher Bawono Kumoro argued in a recent article.

"Psychologically, voting rights would encourage military men and women to take more responsibility for Indonesia's democracy," he wrote.

"They would realise their highest duty is to protect this democracy, and as a result would not be easily mobilised to support a certain political party."

Interestingly, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono is one of the strongest proponents of a military no-vote, as are many other old senior generals. In 2012 and again this year he has said the time is not yet ripe for the armed forces to have voting rights.

A former chief of staff for social-political affairs and head of the military faction in the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR), Dr Yudhoyono is now chairman of the Democrat Party, which finds itself on the sidelines of pre-election coalition-building.

The armed struggle against the Dutch colonial administration provided the Indonesian military with the legitimacy to involve itself in practical politics when it finally achieved full independence in 1950.

The military and police cast ballots in the 1955 legislative elections, but under the New Order regime's dual-function doctrine, they were banned from voting and instead given seats in Parliament and the MPR, the country's highest legislative body.

That arrangement was phased out in the early years of the democratic era, with the police separating from the military and the armed forces gradually withdrawing from active political life.

Indonesia remains the only country in the Asian region to ban the military from voting. There are, however, as many as 15 nations, mostly in South America, Africa and the Middle East, that still adhere to the practice.

Dr Yudhoyono is worried it will lead to disunity between officers and rank-and-file soldiers. He wants to wait until the country's political system has matured and democracy has been fully consolidated.

In the end, however, preventing military and police from voting is based on the false premise that it is a political act, rather than a basic democratic right. It is time Indonesia accepted that and left its historical baggage fears behind.