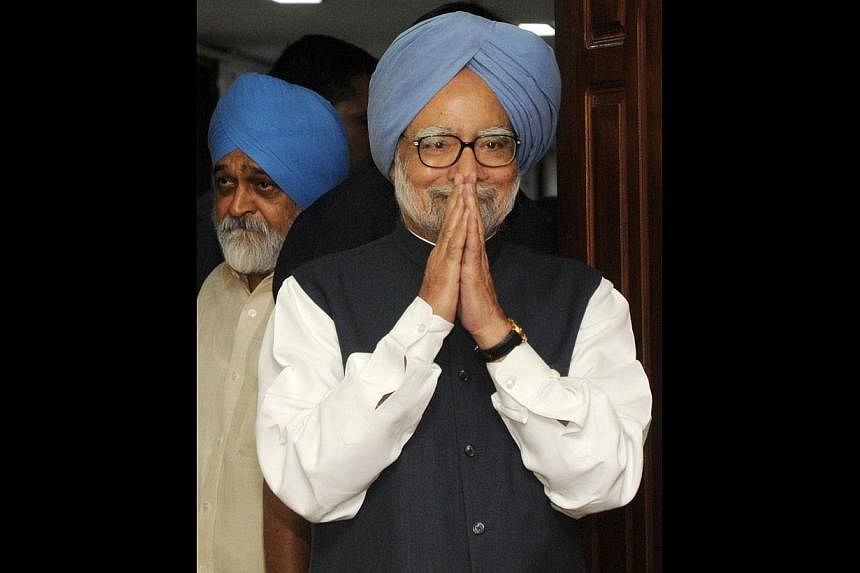

IN EARLY March, a few days after the shock resignation of his navy chief over a string of accidents involving naval assets, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh invited Admiral D.K. Joshi and his wife to a farewell tea at his residence. There, looking at India's first armed services chief to quit on an issue of moral responsibility, India's first Sikh prime minister perhaps felt he owed the gentleman-officer a word of explanation.

"Admiral, there were many times when I, too, thought of resigning," said Dr Singh, who comes from a community with a long martial tradition. "But every time, I thought of the nation and decided to stay on."

These words, never before reported, underscore the paradox of Manmohan Singh.

Insulted

HIS well-wishers, and, if his former media adviser Sanjaya Baru is to be believed, even one of his three daughters, would have liked him to quit mid-term, particularly last year when he was insulted by his fellow party man and putative successor - two-time MP Rahul Gandhi.

That was when Mr Gandhi unexpectedly showed up at a Congress Party junior leader's press conference to attack legislation just passed by Dr Singh's Cabinet that would have effectively voided a Supreme Court order banning from Parliament those who had received criminal convictions. Calling it "nonsense", Mr Gandhi proceeded to dramatically tear up a copy of the ordinance.

The Prime Minister was abroad at the time for a meeting with US President Barack Obama, and India's frenetic media feasted on the news of the clash within the Congress. Many, including Mr Baru, wanted Dr Singh to quit immediately to save himself and his office from being demeaned by the upstart Congress vice-president whose farcical intentions, clearly, were to distance himself from the government so influenced by the party headed by his mother, Sonia.

But, at the time, like countless occasions before when his writ did not run past the powerful Gandhi clan, Dr Singh stayed on, swallowing the phlegm.

Some critics say he did so because he, or people in his immediate family, had come to enjoy the trappings of office and were reluctant to let it all go. Others, who remember the lengthy bio-data of Dr Singh that his office would put out, detailing even district-level Rotary Club awards, think he was chasing a record of being the only prime minister since Jawaharlal Nehru to serve out two consecutive full terms.

The most charitable explanation - and his words to Adm Joshi bear this out - was that Dr Singh may have been reluctant to make way for a possibly corrupt successor who may have been pitchforked to office merely on the basis of his personal loyalty to the Gandhi mother and son.

Either way, history will record that Dr Singh, whose personal integrity is unimpeachable, was unable, or unwilling, to intervene as he presided over what is generally regarded as India's most corrupt period since the nation's independence from British rule in 1947.

Indeed, his silence was so resounding that it had become the subject of jokes around the nation. At a concert by top Indian and Pakistani musicians at Singapore's Star theatre last year, the Indian master of ceremonies began by requesting that the audience "switch your cellphones to Manmohan Singh mode".

A mixed record

YET, to judge Dr Singh on the basis of the many scams that marked his second term is not to get the full picture of the man or the government he ran for 10 years, however timorously at times; for the full record is mixed.

Among his top achievements, no doubt, is that India enjoyed a period of social harmony, a not insignificant achievement for a nation whose religious communities - and castes - have often clashed. While his own background as a minority Sikh played a small part, recent research also indicates that the strong growth registered in his first term starting 2004 - thanks to the sound economy he inherited from the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government - also contributed to social peace as people focused on improving their lives.

But growth has slowed significantly in his second term on the back of his government's policy paralysis and persistently high inflation that has needed more than a dozen interest rate increases.

Sadly, his last two years have seen average economic expansion of less than 5 per cent, bringing to the surface once again the acid label of "Hindu rate of growth". Worse, he failed to over-rule a dirigiste finance minister who slapped a retrospective tax on key multinationals such as telecoms giant Nokia, scaring away investors.

"His credentials as the architect of the 1991 reforms were an important factor in his being chosen prime minister, yet the promise that his elevation held remains only partially fulfilled," the respected newspaper The Hindu said in an editorial yesterday.

The tide turns

IN HINDSIGHT, if there was a point at which the tide began to turn for Dr Singh, it would probably have to be placed at January 2010, when he moved out his straight-talking national security adviser (NSA) M.K. Narayanan to a governor's post.

Although the push came from people close to 10, Janpath - Mrs Gandhi's residence - Dr Singh responded to it with alacrity. Mr Narayanan was a former spymaster who always took a hard-eyed view of Pakistan and China. Dr Singh hoped that a more pliant NSA would help him build the bridges with key neighbours, particularly Pakistan, that he desperately sought.

But Mr Narayanan also had other uses, chief of which was direct linkages to almost every top politician in India, thanks to his years in the Intelligence Bureau. His absence from New Delhi would rob both government and party of critical advice and a trusted interlocutor with nettlesome regional leaders such as West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee and Mr Muthuvel Karunanidhi of Tamil Nadu.

Sadly for Dr Singh, the expected foreign policy breakthroughs would not come, regardless of the change he made. Under pressure from allies in West Bengal state, which shares a border with Bangladesh, he had to renege on a deal to give that country a larger share of common waters, severely angering the friendly Sheikh Hasina government in Dhaka. Tamil Nadu's politics prevented him from building a closer relationship to the strategically perched nation across the water, Sri Lanka, where China is making rapid inroads.

And his dream of visiting Pakistan, the land of his birth, remains unfulfilled because the civilian government there is in no position to cut a deal with New Delhi on the key issue of Kashmir. Meanwhile, China has been making several border probes along their undemarcated frontier and finding the Indian response weak.

Domestically, the Congress-led government ran aground and made several political bungles, notably in its stronghold of Andhra Pradesh, where it had won 34 of the 42 parliamentary seats in 2009. Today, it is on the threshold of being decimated in the southern state after agreeing to split the province to cater to local sentiments in one region, Telengana.

Dr Singh's only notable foreign policy success was the nuclear deal with the US, which helped lift global sanctions on India's nuclear programme and enhanced its strategic elbow room in Asia.

But even the US account has gone "off the rails a bit" as a senior Indian diplomat told me recently. American companies such as Westinghouse Electric are shying away from building nuclear plants in India, thanks to onerous legislation and responsibility clauses. The US also bungled the treatment of an Indian diplomat arrested for making false declarations on the money she paid her domestic help in New York, leading to the withdrawal of special privileges accorded American diplomats in India and part of their security.

Disappointment

COULD Dr Singh have done better? Certainly, he could.

In 2009, his government was returned to power with a larger majority because people saw in him an honest and competent administrator, the very qualities for which they are now looking to the Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP) Mr Narendra Modi. Rather than using this victory to assert himself, and put his own stamp on government, Dr Singh too meekly yielded to his coalition allies and the Gandhi household, which determined key decisions for him, including his Cabinet line-up. Mr Baru, his former media adviser, reveals in a recent book that Dr Singh told him he had reconciled to the fact that "there cannot be two centres of power".

The consequences have been lethal for not only his image, but his government and party as well.

Perhaps it is fitting then that the last word on Dr Singh should come from a senior politician of the rival BJP. "The Prime Minister goes out with dignity and grace," Mr Arun Jaitley, leader of the Opposition in the Upper House, where Dr Singh, too, is a member, said in a blog post on Tuesday. "He will remain an elder statesman and a man of credibility to guide the nation. Only if he had stood up at the right time and disagreed, he would have been regarded with still greater honour."