THIMPHU - One of the most picturesque scenes from Bhutan is that of the snow-fed Phochu (male river) and Mochu (female river) merging to form the Punatsangchu.

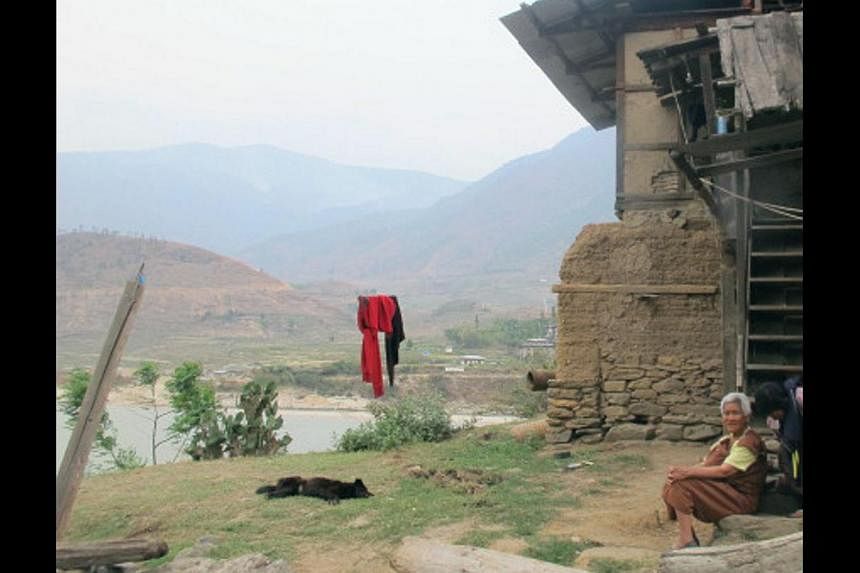

Thousands of padi farmers live in the fertile Punakha-Wangdue Phodrang valley, the rice bowl of western Bhutan. The peaceful, rustic image it presents is postcard pretty, but it also belies the rising dangers the villagers face as a result of warming temperatures.

Ms Tshering Zam, 49, a farmer from Tsokona on the left bank of the Punatsangchu, worries each time it looks like rain.

The river, which feeds her crops, is a growing menace as it encroaches ever closer to her traditional mud, stone and wood house each passing year. She stores her grains and other valuables at her sister's house, which is located farther away from the river.

"My three sons and I sleep in our neighbour's house every time it rains," she said. Her house, located just a few metres from the Punatsangchu river, falls within what is classified as the red zone, or high-risk area.

Areas on both banks of the river have been categorised as red, yellow and blue zones (high, medium and low risk) based on the degree of risk to lives, property and infrastructure.

Ms Tshering Zam has lived through several flash floods, including two from glacial lakes bursting their banks. The most recent one in 1994 washed away five watermills, 16 yaks and tonnes of grains and inundated large swathes of pastureland, she recalled.

"I remember how the slope there fell into the river," she said. "The volume of the river is increasing every year."

Bhutan is highly vulnerable to what are known as GLOFs (glacial lake outburst floods) as glacial ice melts. Of its 2,794 glacial lakes, 25 have been identified as potentially dangerous.

But flooding is not the only threat to farmers in the area.

Erratic rainfall and rising temperatures are also hurting Bhutanese, almost 70 per cent of whom live in villages and depend on subsistence agriculture for a living.

As temperatures rise, farmers like Ms Tshering Zam's neighbour Pasa Bidha, 55, say they are having to fight a drastic increase in pest infestation of their crops of chillies, beans and tomatoes.

Meanwhile, landslides and flash floods take a toll on roads and other infrastructure.

But one of the biggest concerns is Bhutan's heavy dependence on hydro-power for revenue and jobs. The country's three major hydro-power projects of Kurichhu, Chukha and Tala have a capacity to generate about 1,400MW of power. Thousands of people are employed in this sector and heavy investment is being made to step up production to 10,000MW by 2020.

Bhutan hopes to sell more hydro-power to fuel economic growth but climate change poses a multi-faceted danger to this goal. There is the threat of increased flooding as glaciers melt. At the same time, Bhutan is also vulnerable to water shortages as weather and snowfall patterns grow more erratic and disruptive.

GLOFs and landslides could also damage hydro-power plants.

In the meantime, officials are keeping a close watch on the lakes and doing the best to drain the water from them.

People living along the Punatsangchu are also depending on GLOF early warning systems installed along the riverbanks.

Sirens are supposed to go off should a lake burst its banks upstream, giving people living downstream time to evacuate.

As for Ms Tshering Zam and her sons, it took three years to get the paperwork done for an alternative plot of government land on safer ground but, in time, it will mean not having to fear every time it threatens to rain.

KUENSEL/ASIA NEWS NETWORK