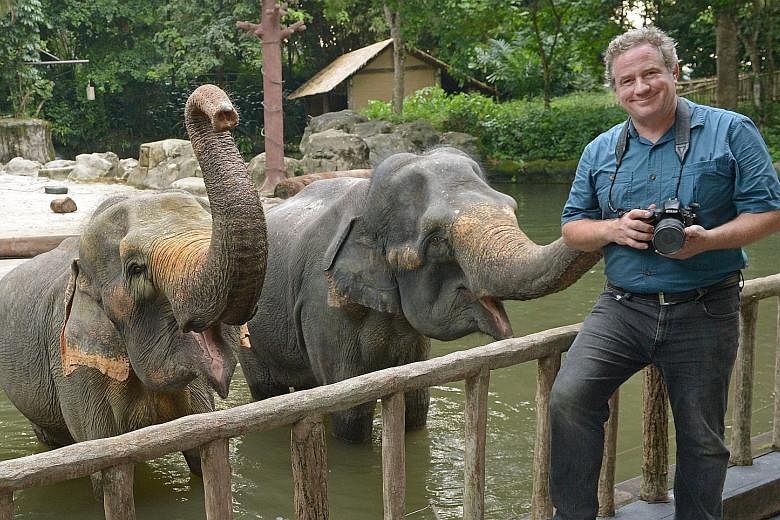

A huge proboscis monkey at the Singapore Zoo has given National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore great cause for celebration.

Last Thursday, the animal, known for its distinctive long, pendulous nose, played model for Sartore and became the 6,000th species to be a part of the National Geographic Photo Ark, a mammoth project to photograph every species in captivity.

This means that Sartore is halfway through the 25-year project, which he started 11 years ago. The jovial 53-year-old notes that there are an estimated 12,000 animal species in accredited zoos and aquariums.

In his quest to capture the raw beauty of each living creature, he shoots only against a plain black or white background.

"In such a setting, a tiger is no more important than a tiger beetle. The Photo Ark is really to celebrate and give a voice to these animals, even the tiniest ones," he explains.

Singapore is his first picture pitstop at a South-east Asian zoo, aquarium or wildlife centre.

He arrived here 13 days ago and has shot 150 species at the four wildlife parks - Singapore Zoo, Night Safari, River Safari and Jurong Bird Park - under the Wildlife Reserves Singapore.

From the critically endangered freshwater Singapore crab to the gentle wildebeest to a tiny insect, the water strider, each has "immense value" in Sartore's eyes.

The American flies back home to Lincoln, Nebraska, today before continuing his global quest in Spain later this month.

Sartore has peered deep into the eyes of animals both big and small, endangered and rescued in more than 300 wildlife sanctuaries across six continents and wants the world to do so too.

"If I can get the public to look into the eyes of these animals to get them to care, we might have a chance of saving them," says Sartore with a determined glint in his eye.

Turning sombre, he drops hard and heavy facts about the necessity for mankind to sit up and pay attention to these species. "Half of them could go extinct at the turn of the century and it's folly to think that it won't be very detrimental to humans too," he says.

Sartore, a father of three, first felt the urge to make a bigger impact when his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer and he had to be back home in Lincoln for a year in 2005.

He had time to think about the next phase of his life. He started visiting the local zoos in his area to photograph animals and, after noticing how popular the shots were when shared by the National Geographic magazine, realised the potential.

He says: "The photos of each animal are an opportunity to get people into the tent of conservation and think about how they live their lives, be it the car they drive or food they eat."

On the road two-thirds of each year, the passion project is all Sartore ever thinks about. Spending 100 to 110 hours working each week, he is constantly mapping out where to head to next and what animal to shoot.

The shoots are no breeze either as he has to consider the best way to make each shoot as comfortable as possible for each species.

Photographed in their enclosures, the conservationist either shoots through the bars of the cage if it is a dangerous creature or he places small, fast-moving ones in a specially built soft-cloth white tent.

Depending on each species, a shoot might take a couple of minutes to hours, though he notes that many of these captive species are "very used to seeing people daily" and quickly "figure out that having their photo taken is no big deal".

Unsure if he will be able to shoot all the species in captivity, he asserts that he will die trying. "I wish I had started earlier," he says.

And in case he does not complete the project, his eldest child Cole will take over. In fact, the 22-year-old joined his father during the trip here as he was on his school break.

"He knows how to light, shoot and edit, but he can't do it as long as I can move," Sartore cheekily adds.

• Go to nationalgeographic.org/projects/photo-ark/ for more information.