It's a white, wild, wonderful world: Explore Antarctica with Lee Siew Hua

To cruise in Antarctica is to gaze on a landscape of icebergs; spy penguins, whales and seals; and trek remote, dreamy islands

On a frozen summer's day in Antarctica, as we cruise among icebergs under a lustrous sky, a playful minke whale appears.

Its immense head rears up alongside each of our seven inflatable Zodiac boats, inspecting the elated travellers from afar.

Minkes are known to be curious and soon this behemoth dives under my rubber dinghy, a sleek swish of dorsal fin on a torpedo-shaped body, so close that I discern the delicate golden algae on the whale's skin.

That moment distils Antarctica for us: wild and riveting. It is like another planet, or the closest we will get to one.

I am on a 12-day voyage to the crystal continent on the small, all-suite expedition ship Hebridean Sky, which hosts 100 passengers.

Fleetingly, we cross into a world of endearing penguins, wandering albatrosses that circumnavigate the globe solo, and wildlife from sea, shore and sky.

Our days are spent trekking on small islands, each with a different beauty and mystery.

Once, we have a fun polar plunge in our swimwear, on an afternoon when the temperature is a milder 2 deg C.

Antarctica is the coldest, highest and windiest continent, and does not belong to any country. Nobody lives there except for researchers studying cosmic rays, seismology and other esoteric sciences in the southern hemisphere.

Only during the long austral summer, from November to March, will cruise ships arrive, though I do not spy another vessel in the vastness.

Just 35,000 travellers showed up during the 2015-2016 season and, like us, they traversed insignificant slivers of the 14-million-sq-km continent that is almost twice Australia's size. In comparison, 224,755 tourists cruised in the Galapagos Islands, another fragile and exotic locale, in 2015.

Everything is on an off-the-charts scale in Antarctica. In July, the Larsen C Ice Shelf - a floating platform of ice - shed a chunk of iceberg eight times the size of Singapore.

And in recent months, a coalition of countries created the world's largest marine reserve in Antarctica's remote Ross Sea, a zone of 1.5 million sq km. Replete with plankton and krill, the Ross Sea feeds multitudes of whales, penguins and other creatures - good news for travellers as Antarctica may be even richer in wildlife.

PENGUIN PARADISE

In this little-seen terrain, penguins are the stars, waddling clown-like on ice, but porpoising gracefully over water like wee projectiles.

There is something Edenic when inquisitive penguin chicks walk up to humans with little fear, or let us observe their antics while we pretend to be part of the landscape.

The downy fledglings, at six weeks old in February, are about the same size as their mothers, which they chase and harass hilariously to be fed.

To be metres from thousands of penguins - as they preen, squawk, hop over little obstacles, slip on ice, look us in the eye - is extraordinary. For days, we never tire of watching the flightless birds snooze, nest on pebbles - or moult.

The moulting birds stand alone like outcasts, forlorn, looking into the distance as they lose feathers from their waterproof "dive suit" over three weeks or so. They are vulnerable, unable to swim and hunt, and their bodies are cold.

Paradise has its dark side, inevitably. Once, a bold baby penguin steps away from its colony to cuddle against our legs on Cuverville Island. But while trotting back, it is attacked by a skua, a predatory seabird. The chick hurtles back to the safety of numbers - just barely - while the adult penguins turn on the invader.

Then there is the guano. While we love watching penguins in their natural habitat - from the sparkling shores to the uplands with wind-whipped polar vistas - some of these places reek of droppings. We have to keep our balance on the slime left on paths as well.

So this is a place of purity and sludge, though, ultimately, Antarctica shows me that the world will never run out of wonders.

Over the days, we admire three species of penguins. There is the little Adelie with a white ring around the eye, while the long-tailed Gentoo throws back its head when it calls.

My favourite, the Chinstrap, looks like a tiny jaunty aviator with a black-capped head and a line of black feathers under its chin.

There are 18 species of penguins in the world, all found in the southern hemisphere, except the Galapagos penguin at the equator.

What about polar bears? They roam the Arctic Circle up north, not Antarctica.

Such insights are dispensed, entertainingly, by our team of naturalists and expedition leaders who step onto land with us and give talks on the ship. We learn about all things Antarctica, from climate change to clouds to heroic quests to this frontier, the lectures stopping when a passing whale is spied and we pelt out to the decks to look.

WHALE SONGS

Once, when I am reading on the balcony of my cabin, I hear a puff of air by the ship. I lean over the balcony in time to glimpse three humpback whales powering past our ship, metres away. One whale does the classic tail-up dive into the icy depths.

"Fluke!" a passenger from another cabin yells, while others whoop joyfully at the sight of the fluke or dramatic double lobes of the tail.

Ms Annette Bombosch, a young German marine biologist on the ship's expedition team, later regales us about the "complex courtship song" of the humpback whales. She plays a sound sample of the music from the deep spaces of the ocean.

Humpbacks migrate 8,000km or so, she notes, and their tremendously long flippers are up to one-third the length of their dark-grey bodies. Mothers nurse their infants with rich milk with a 50-per-cent fat content.

Many other animals make their home in Antarctica, and we spy busy Snowy Sheathbill birds on land while slender, sociable crabeater seals flop on ice floes.

And, shortly after the minke whale appears, a leopard seal, distinguished by a majestic head, plays peek-a-boo for long moments with us before baring its fangs.

POLAR PLUNGE

The landscape, with its icy incandescence, beguiles as much as the wildlife.

And while Antarctica is covered by an ice sheet and we associate it with an all-white world, the scenery is everchanging with a dynamic variety of islands and channels, coves and calderas, highland meadows and jagged cliffs - sometimes illuminated by summer rays, sometimes like a moody-blue Lord Of The Rings realm.

The scenes of Deception Island play on my mind. The island is really a rim of land encircling a caldera, which is the crater of an active volcano that has collapsed on itself.

Deception Island hosted a whaling station in the previous century, but the place is like a dystopia now, with the abandoned shells of giant blubber boilers and tilting oil tanks. Elephant seals, which grow up to an intimidating 6m, rest among the rust-red wrecks on tindery volcanic sand.

The sensation of a lost world is heightened by the storm-grey sky and chilly drizzle, while the ship's historian, Mr Seb Coulthard, a Briton and gifted storyteller, conjures up the isolated life of long-gone whale hunters.

"They took a lot from Antarctica, but Antarctica took everything from them," he says, at the untended cemetery.

Before we leave, there is a moment of levity when some of us take a polar plunge (and get a certificate for that later). This is a geothermal zone so wisps of steam are rising from the sea, though the air temperature hovers at 2 deg C.

We ham-handedly remove unwieldy layers over our swimwear and bound into the sea, in ones and twos, yelping and paddling wildly for a few seconds.

I emerge, only to have our American voyage photographer Will Rogan say apologetically from the beach: "I didn't take your photograph." Someone has distracted him.

We stare at each other helplessly before I say: "Okay!" and plop back into the water before I change my mind.

I race back to shore and discover I am on a high after the double dip. The inner glow lasts for hours.

RESPLENDENT, HIDDEN

Neko Harbour is another island I love.

Unlike Deception Island, the sky is scintillating and the turquoise-tinged icebergs are reflected in the mirror-smooth bay that afternoon. It is perfection to simply sit, among the penguins, and savour the great unknown that is Antarctica.

At 7pm, some of us return to Neko Harbour to observe two dozen high-spirited passengers who have snagged spots to camp overnight. They are housed either in tents or "bivy sacks" - akin to waterproof sleeping bags - set in the snow.

Like many others, I cannot get a coveted spot, but I am soothed to be here in the still-luminous evening.

It is the same landscape, but much quieter, though the penguins have not fallen asleep and there is some chirruping at 10pm. I cherish the feeling of being alone with the calving icebergs and the first stars.

The next day, a young Hong Kong-based lawyer originally from China's Jiangsu province, who wants to be known as Maggie, describes her night cocooned in a bivy sack, with just a sheet between her and the firmament.

"Parts of the sky were dense with stars - it was the Milky Way, and I had always wondered what it looked like. I saw shooting stars. Pockets of the sky were in twilight and not completely dark," Maggie, 38, recounts.

"I started to hear the sounds of the island - glaciers and penguins in the distance. It wasn't cold and I fell asleep to natural sounds around midnight."

For those who have journeyed to Antarctica, it is likely their seventh and final continent. That makes Antarctica powerfully symbolic so it lingers in memory, and we never truly leave the place.

It is our last morning when the playful minke whale spies us. In whale-hunting countries such as Norway and Japan, magnificent minkes are prey.

But in Antarctica, the marine mammal is fearless, much like the inquisitive seals and birds I once walked among in the Galapagos Islands of Ecuador, and these are among the rare Edenic domains left on Earth.

GETTING THERE

I fly on Qatar Airways (www.qatarairways.com) from Singapore to Buenos Aires and explore the Argentine capital for two days. Then I take a domestic flight on Aerolineas Argentinas (www.aerolineas.com.ar) to Ushuaia, spending another night in this land of wild Patagonian peaks. The southernmost city in South America, Ushuaia is a jump-off point for Antarctica cruises and I board the expedition ship Hebridean Sky here.

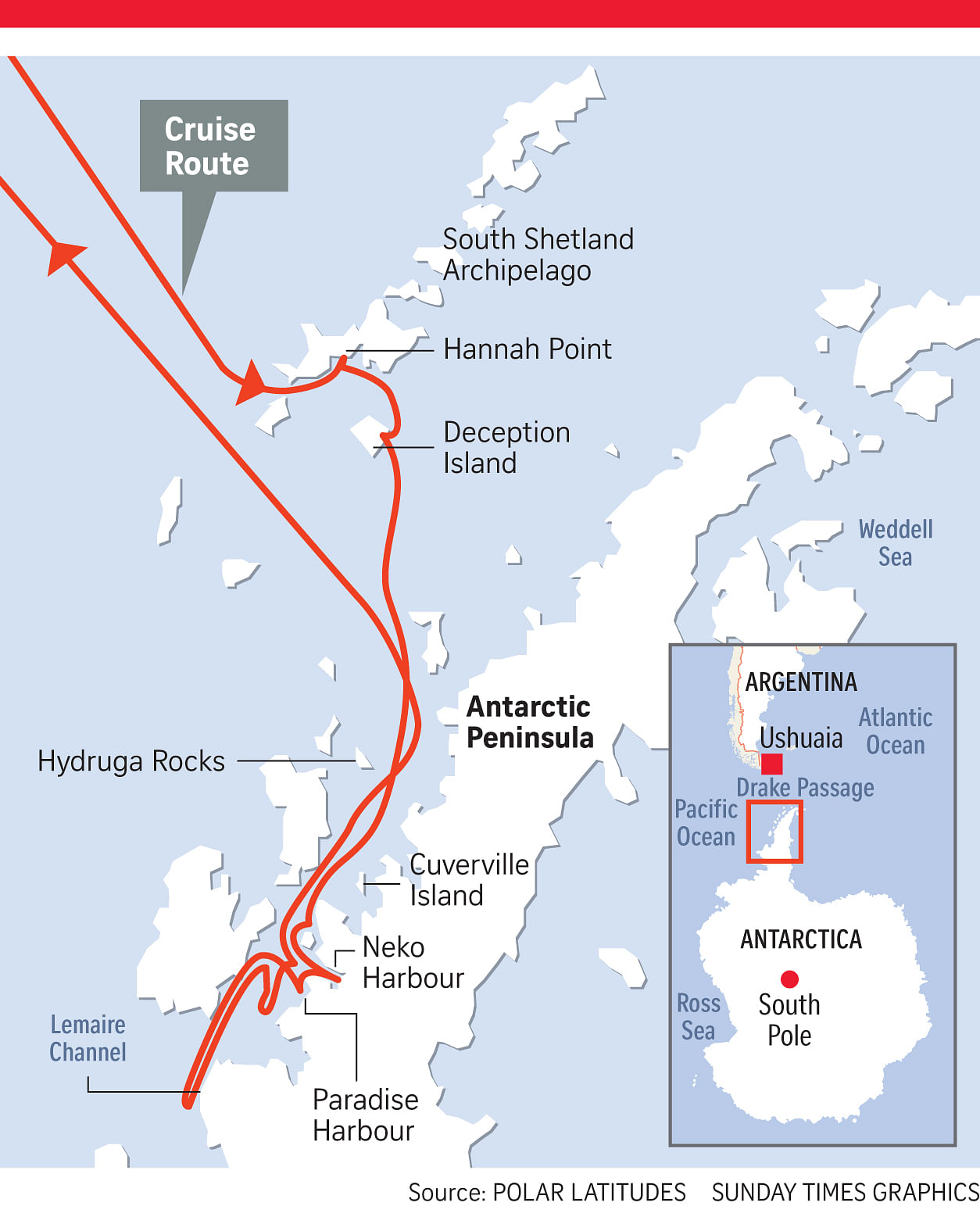

From Ushuaia, it takes two days to cross the Drake Passage to the Antarctic Peninsula, where guests land on small islands to observe wildlife for five days. There are Zodiac cruises, kayaking and an overnight camp on ice.

Antarctica cruises on the Hebridean Sky can be booked through luxury travel brand A2A Journeys (www.a2asafaris.com).

The cruise season is short, stretching over the austral summer from November to March. The peak season is from December to January.

Rates for a 12-day trip start at US$7,295 (S$9,950) a person, based on triple occupancy on the ship, for the upcoming season from November to March next year. The price includes an en-suite cabin, meals with wine on board, expeditions in Antarctica (separate rates for kayaking and camping apply), lectures by experts and a night's accommodation in Ushuaia, Argentina. All flights are excluded.

For the season from November next year to March 2019, book before Dec 31 to enjoy a discount of US$1,500 a person, for selected suites. Choose from itineraries varying from 11 to 22 days.

For more information, call A2A Journeys on 6442-7600 or e-mail enquiry@a2asafaris.com.

TRAVEL TIPS

• Prone to seasickness? Do not be deterred, even if the Drake Passage between Antarctica and the tip of South America - where most cruises begin - is notoriously rough. I take motion sickness pills, walk like a penguin for balance and keep one hand free in case I need to grab a railing. The rolling motion that causes seasickness is greater on the upper decks, so consider a lower-level cabin, which tends to cost less too.

My two-day crossing is relatively calm, while Antarctica itself is sheltered. The return on the Drake Passage, however, is wilder and I lie down a couple of times. In perspective, travellers "earn" the prize of Antarctica with this rite of passage.

• To observe or photograph wildlife, move slowly or stay still, and remember that animals have the right of way here. Let them come to you: curious penguin chicks cuddle against our legs.

Respect a 5m distance from penguins. Keep 25m away from jousting elephant seals.

For compelling pictures, our voyage photographer Will Rogan suggests getting on eye level with the wildlife. Also capture their eyes so the image is "alive".

• The weather is changeable and thataffects whether each day's plan for landings or kayak expeditions can go on. Keep in mind that the continent can be inhospitable and potentially dangerous.

Keep up a light fitness regime before arrival. The daily expeditions involve some walking on ice or slopes and may last two or three hours.

Keep warm by dressing in layers, including waterproof pants, boots and a lightweight, windproof expedition jacket. A full packing list will be given.

• Choose a small ship as only 100 passengers at a time can go ashore in line with Antarctic regulations. Ships with more than 500 guests cannot send anyone to the fragile terrain; wildlife and vistas are admired from afar.

• Read up first to appreciate the exceptionalism of Antarctica.

• Follow Lee Siew Hua on Twitter @STsiewhua.

• The writer was hosted by A2A Journeys.

• This is the first of a two-part story.

NEXT WEEK: ANTARCTICA AND THE APPEAL OF FAR-FLUNG PLACES

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on October 01, 2017, with the headline It's a white, wild, wonderful world: Explore Antarctica with Lee Siew Hua. Subscribe