Play: Emily Of Emerald Hill (written in 1982, first staged in 1984 in Malaysia, staged in Singapore in 1985)

Playwright: Stella Kon

What it is about: A charming Peranakan woman, Emily Gan, evolves from frightened young bride to a strong-willed matriarch. She tells of her deft manoeuvring in a new household to endear herself to her mother-in-law, her son's mysterious suicide and her husband's infidelity. The audience rejoices with her triumphs, but also feels deeply for her heartbreak and regrets.

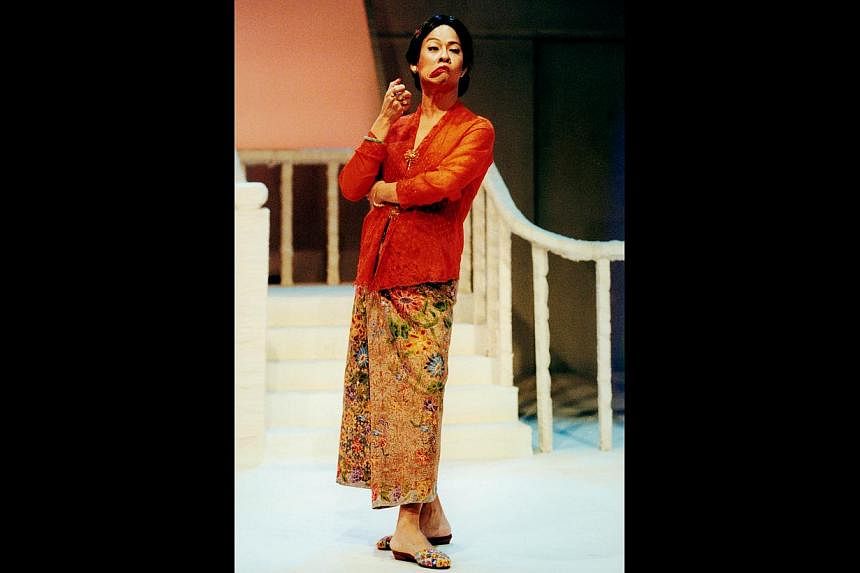

Singapore theatre's most famous silhouette wears a tailored kebaya and beaded slippers. She sits alone, amid the imagined ruins of an empty house and finished feasts, haunted by her past.

Emily Of Emerald Hill marked a turning point in Singapore theatre and, ironically, its first performance was not in Singapore but in Malaysia.

An opinion piece in The Straits Times in December 1984, written by theatre critic Kate James, demanded: "Come on Singapore, stand up for your own plays", and asked: "Why haven't Stella Kon's prize-winning plays been performed in Singapore?"

By that point, the playwright had won the National Playwriting Competition three times: for Emily (1983) and two other plays - The Trial (1982), in which Socrates is on trial in the Republic of Singapore and the audience must vote on whether he should live or die; and The Bridge (1977), an intricate study of inmates in a drug rehabilitation centre putting on a musical. But her work was never produced.

The first director to tackle the seminal monodrama was Malaysian teacher Chin San Sooi, when a mutual friend handed him the script. Chin, now 70, was enthralled.

Speaking to Life! over the telephone, he says that several other directors had expressed reservations that a single actress would be able to carry the 100-minute show.

"The fact that it was a one-woman performance must have been the big problem with Singapore then as well, because nobody had stepped on that kind of terrain," he says. "It was because of that, I think, that people didn't want to handle it. But I thought, here is a gem of a play. And it can be done."

Malaysian playwright Leow Puay Tin was the first Emily, holding her own in a Seremban sports club surrounded by rubber trees. The venue was so remote that cables had to be drawn for nearly 500m so that there would be electricity. But the play was greeted with acclaim and applause, with one critic describing Leow as "superb".

It was the same can-do attitude that swept the play onto the Singapore stage a year later, when director Max Le Blond and actress Margaret Chan (then several months pregnant) took up the mantle and set a nation's imagination alight. It was performed at the 1985 Drama Festival.

Chan, now 65, still recalls with disbelief that "whole audiences would burst into tears". There was just something about Emily, her climb from rags to riches and descent to emotional rags, that resonated with the Singaporean consciousness.

The associate professor of theatre at the Singapore Management University says: "I believe that Stella wrote the play in a matter of weeks, and that remains the best - because it's not 'crafted', in a sense, she didn't have to go and consciously put in all these structures.

"It came from her heart and soul. So it was very real. The character, the circumstances, were completely recognisable."

In writing Emily, Kon was inspired by a talk with a theatre colleague who mentioned the monodrama format in the light of submissions for the National Playwriting Competition - as well as the feisty personality of her grandmother.

Her grandmother was not a child bride, neither did she have an unhappy marriage plagued by the death of her son. But her exuberant, larger- than-life personality became a template for Emily.

She says: "Grandma was loved by all of us and my cousins all remember her till this day as a bustling, busy woman, arranging everything. But then I started to reflect a bit more closely to ask - why?

"Why was she arranging everything? Why did she even continue to do the marketing and shopping and general helping out, even when she had daughters-in-law who had moved to the old house? Why was she still the managing matriarch?

"Thinking back to all the stories, I began to see the power that women had then. Were she to live in this time, she could have been the CEO of a business, but since she didn't, she found these outlets which were partly built into those social structures."

Kon, 70, wrote vignettes first, before eventually moving the scenes around into a coherent sequence. She did this manually with scissors, glue and a ring punch binder so she could move the pages around.

She recently donated one of the original complete manuscripts of Emily, yellowed and typed out on one of the earliest generations of Apple word processors, to the Peranakan Museum.

Emily put audiences under her spell and she was later performed by Malaysian actress Pearlly Chua, who would inspire Singapore thespian Ivan Heng to step into the gender-bending role that would kickstart his theatre company, Wild Rice, and bring Emily to a new generation of Singapore audiences in the late 1990s and 2000s.

Heng, 50, says: "I think every woman can see herself in Emily - and you see a lifetime, from a girl of 14 until she's old in her rocking chair. Travelling with the play around the world, all kinds of women - Indian, Jewish, Korean, American... would say, 'That's my mother' or 'That's my grandmother. Thank you.'

"We all understand it because we still have to live in a man's world, and sometimes still have to play the role of women in order to survive. Sometimes they don't have a choice and have to play the politics of the kitchen and the bedroom."

More than 30,000 audience members have seen Heng as the Peranakan matriarch, a mark of the play's ability to transcend the passage of time.

While the monodrama is hardly cutting edge today, the success of Emily in terms of format and audience reception marked a fertile period for Singapore theatre in the 1980s.

The then Ministry of Community Development, which had organised the 1985 Drama Festival, wanted to repeat Emily's success by heavily publicising future National Playwriting Competitions.

A deputy director at the ministry said: "Emily proves that there is a Singaporean audience appreciative of Singaporean works."

Emily was invited to the UK's Commonwealth Arts Festival and also travelled to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 1986 (with Chan performing in both instances), helping to shatter the illusion that Singaporean theatre could not stand on its own feet on the world stage.

And while then journalist and now theatre educator T. Sasitharan cautioned against a lack of depth in the theatre, with companies churning out work after work like a production line, he also noted in a December 1989 article for The Straits Times that "the ghost of aversion to home-grown plays, born of an inferiority complex which haunted the scene at the beginning in the 1960s, was finally laid to rest" with Emily and the plays that followed it.

These included Kuo Pao Kun's The Coffin Is Too Big For The Hole (1984) and the Dick Lee-Michael Chiang blockbuster musical, Beauty World (1988).

Many home-grown theatremakers, such as Ong Keng Sen and William Teo, had begun to pull away from the conventions of Western theatre and experiment with a performance idiom of their own. These were the makings of a unique Singapore lexicon in theatre that would eventually become the norm.

Nearly three decades later, Emily remains a beloved play, even if the references in the script have started to age.

Chan reinhabited the role for an exhibition on the play at the Peranakan Museum that ran from 2012 to last year, and Chua performed it at the Damansara Performing Arts Centre in April this year.

Kon is also working with director Samantha Scott-Blackhall on a musical version of Emily, slated to run in the later half of next year. She is writing the lyrics.

After watching Emily in 1985, the late Malaysian theatre director and luminary Krishen Jit wrote in a commentary for The Straits Times: "I left convinced that Singapore theatre is primed for a history.

"If current linguistic trends prevail, the English-language theatre of Singapore promises to be the custodian of the future.

"In such an event, the performance of Emily might well be the entry point to a viable and distinct Singapore theatre."

He was right.

Emily Of Emerald Hill is available from Select Books at $16 (before GST).

The next instalment of this 15-part series will be published at the end of next month.