Only one production has been able to send a spurt of nervousness coursing through Oliver Chong's veins.

"I don't remember ever being nervous on stage," the 37-year-old theatre practitioner declares. "Never... until Roots."

The intimate one-man show premiered in 2012 and proved that something small in scale could be epic in scope. Chong transported audiences on a deeply personal journey, to China and back, to address a muffled scandal in his family history.

Roots, which featured Chong playing a dazzling array of characters, went on to clinch Production of the Year and Best Original Script at last year's Life! Theatre Awards.

Terms such as "virtuosic", "exceptional" and "remarkable" were slipped into enthusiastic reviews. It will be returning to the stage on Thursday as part of puppet theatre group The Finger Players' 15th anniversary season, as one of the company's Greatest Hits.

And Chong is still nervous. He fidgets in his chair, a lustrous rattan spiral, one of an impressive array of vintage acquisitions in his breezy Toa Payoh flat.

He says: "Even before I started rehearsing, I began feeling very nervous and scared. It was strange. I didn't know why. Perhaps it meant so much to me. I've always felt that the play was not mine. It's my late great-grandfather's and my grandfather's. So if I were to fail or do it badly, I might disgrace them."

Chong has traditionally kept two seats empty in the theatre for his late great grandfather and grandfather.

He frets over his chameleonic abilities: "The character is myself, which is the scariest. I guess nobody is completely comfortable with himself? And I feel so vulnerable and naked in front of the audience. I cannot even put up a character to shield myself. It's me. Come, look, Oliver Chong!"

He makes a gargled "wahhh" sound, adding: "It's scary."

But while he has demonstrated an uncanny knack for reproducing a multitude of voices on stage, whether in conjuring up a lively gathering of villagers (Roots) or convincingly channelling a disgruntled and prophetic pet cat (The Book Of Living And Dying, 2012), he has struggled with some inner voices of his own.

He was nine years old when it happened for the first time. It was as if someone had inverted a fish bowl over his head. He could hear the chaotic chatter of voices and the clang of pots and pans, almost as if he were in a noisy kitchen. Everything slowed to a crawl. He waved his hand furiously in front of his face, but it looked like he was dragging it through thick sludge.

Terrified, he told his mother, who told him to get some rest. Perhaps he was just stressed out from school, they thought.

But the voices kept coming back.

Initially they would pipe up when he was by himself, in a quiet space. He would put himself in a noisy environment to avoid them. But the pattern would change and the voices would haunt him in loud situations instead. He thought they emerged only when he was stressed. But then they started occurring when he was completely calm.

He saw a psychiatrist while doing his national service, who diagnosed him with mild schizophrenia and obsessive- compulsive disorder. He also wrestles with depression. But with an almost superhuman sense of control, Chong has taught himself to confront these episodes and then learn to ignore them. It now happens about four times a year.

"It could be happening right now and you wouldn't even notice the difference," Chong says, grinning slightly. "I know how to adjust my speaking and I know that everything is actually moving at the correct pace."

Chong's wife of 10 years, Ms Wai Pei Ceiy, 39, who works in service operations in a bank here, says that he usually knows how to deal with these moments. But she helps out: "I'll take him out. We'll go out for a good dinner, go for a movie, and sometimes I'll say, let's go overseas for a short trip - we like to travel."

The couple have no children.

Ms Wai is one of his staunchest supporters, giving him feedback on his work and sometimes helping out with the front-of-house for his productions.

She adds: "Over the years, you get to know his pattern and you work around it. It's not a big problem. He just needs someone to support him and be beside him. He'll work it out - you just have to be there with him."

None of this has stopped him from honing his skills as a deeply gifted theatre artist.

Chong, who started out as a designer, later began to add every possible theatre trade to his resume. He can act, direct, write, design sets, design publicity materials, make puppets - possibly the very definition of a multi-hyphenate, and these hyphens continue to multiply with every project he takes on.

The "educator" hyphen comes next, it seems, with a seven-week acting masterclass he will conduct next month for The Finger Players, where he is a resident artist-director.

Its company director Chong Tze Chien, 39, declares his younger colleague an all-rounded "consummate artist".

He says: "He's a natural actor for the theatre. It's very rare. I think a person like him comes round only every 10 to 20 years.

"He's one of those meticulous artists who really zoom in on things that people usually wouldn't think about.

"When he writes a script, he'll be obsessed about how he opens the play. Sometimes he will spend months just working on that. He plans out every single thing, and his notes are an encyclopaedia of everything that goes on in his head. He is able to find the beauty in all the details."

As a student at St Andrew's Secondary School, Chong showed early promise in the Chinese art of crosstalk, high-speed banter that requires excellent rhythm, reflexes and a certain charisma.

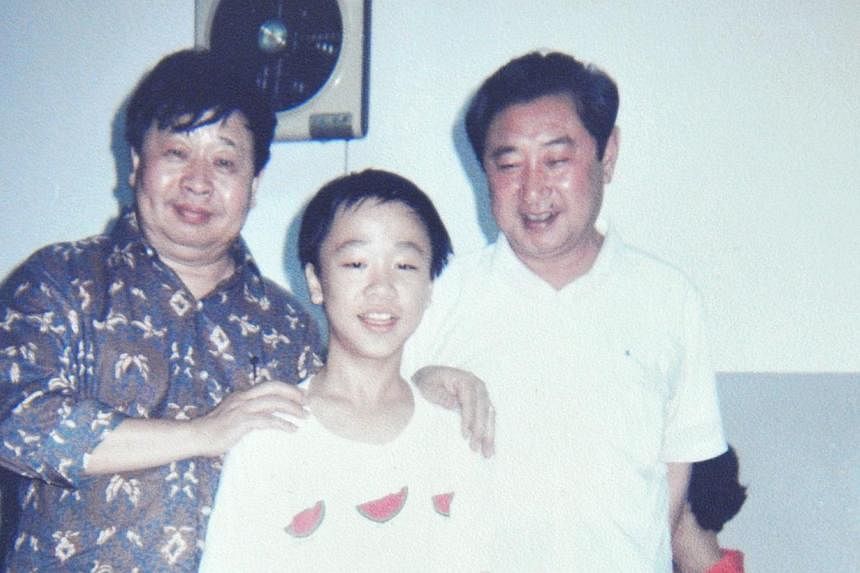

He was taught by stage veterans Johnny Ng and Han Lao Da, and as he took part in competitions, he caught the eye of the late Chinese crosstalk legend Ma Ji, whom, Chong says, personally asked him to go to China to be his apprentice.

His housewife mother and carpenter father were concerned that pursuing crosstalk as a full-time career might be too risky and were also worried about sending their teenage son to a faraway country. They eventually said no.

But his love of performing and of the arts persisted.

He attended theatre performances as a child. His mother took him to watch theatre pioneer Kuo Pao Kun's The Coffin Is Too Big For The Hole in the 1980s, which left a lasting impression on him.

He had a false start struggling through electronic and computer engineering at Ngee Ann Polytechnic for a year, thinking that a practical diploma would be helpful for his professional life.

But he was so overwhelmed by how badly he fit into the programme that he warned his parents: "I'm going to quit at any moment!" - and he did.

He skipped out on his final examinations to visit the Lasalle College of the Arts and the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (Nafa) to inquire about their art and design courses. He eventually decided on Nafa's interior design programme and took extra fine art modules because he loved it so much. His grades were top- notch. In his second year, he started freelancing as a designer to pay for his school fees and also to get a foot in the door in a competitive industry.

His interior design influence is clear from his spotless four-room flat. It boasts clean lines and the odd quirky set piece: papier-mache fish from the play Cat, Lost And Found (2009), an old-school typewriter, a bold painting of lotus leaves in autumnal colours.

Before becoming a full-time theatre artist, Chong dabbled in design, setting up his own firm with several partners. The resulting company, Red Mushroom, "failed terribly", folding in three years. He did freelance design work and worked full time for another company, but quickly realised this life was not for him.

Chong had already been introduced to Chinese theatre company The Theatre Practice through his polytechnic drama teacher. During his national service, a friend working with bilingual theatre company Drama Box asked if he could help to design publicity materials. He agreed. He eventually got roped in to help with set design, given his design background.

When Drama Box's artistic director Kok Heng Leun realised that he was also a capable actor, he cast him in several shows, including Liao Zhai - Of Man, Spirits And The Others (2004) and Shithole (2004).

Chong speaks of Kok with admiration: "When he's directing, he's very much like Pao Kun... what I respect about them most is the skill they have in facilitating actors.

"If the actors arrive at what they already had in mind, they (Kuo and Kok) don't take credit for it. They'll tell the actor, 'Nice job, this is a very good decision.' So they make the actors feel ownership and proud of what they've done. And actors need that kind of morale boost on stage."

While auditioning for a show by The Theatre Practice that same year, he caught the eye of The Finger Players' artistic director Tan Beng Tian, who asked if he wanted to join the group full-time.

He jumped at the chance, having already been astounded by how the group was transforming children's theatre.

After several years of working with the company, he felt compelled to create his own work. His debut was I'm Just A Piano Teacher (2006), a dark tale about a piano teacher who abhors music and later conspires with his maid to kill his parents. The cast carried puppet bodies around their necks, which they manipulated with their hands. It was well received by audiences and critics, who noted its stellar acting and gorgeous visuals.

But Chong had actually panicked after writing the script and asked Tze Chien to direct it instead: "He pulled me aside and said, 'I can do that for you, but do you want me to do that for the rest of your life? If you chicken out once, you will keep chickening out. When are you going to try it?' That was a big slap in my face."

That directorial debut triggered a string of others, including Pinocchio's Complex (2008), about a lonely man whose puppets come to life as his world is crumbling. Then he created Cat, Lost And Found, where a cat falls in love with a female movie usher, dies in an accident and ends up in the body of a man.

These surreal storylines are often adaptations of Chong's vivid dreams: "My earlier productions were very visual and stylised - crazy, dark. Those are things that I prefer. Because that's how I dream."

He lights up when he mentions American theatre director Robert Wilson's surrealist Peter Pan, a spiky, leather- jacketed take on the flying boy who never grows up, full of searing images straight from an eerie cabaret. It was staged here last month as part of the Singapore International Festival of Arts.

"I dream like that!" he exclaims. "I loved it."

Chong's acting prowess also lies in his precise control of his body. He is a physical theatre devotee and has studied various systems of actor training pertaining to the body. For instance, in the Viewpoints and Suzuki training methods, actors aim to develop their physical strength and bodily awareness, then create work based on these methods.

Chong met fellow Singapore practitioners Nelson Chia, Edith Podesta, Timothy Nga and Koh Wan Ching at the Viewpoints and Suzuki Method acting workshops in New York's renowned Saratoga International Theatre Institute Company.

On returning to Singapore, they met weekly to practise what they had learnt and decided to form a loose collective called A Group Of People in 2008. They wanted to create as equals, without a formal leader.

The group had a shock victory when their tiny, experimental piece about urban ennui, A Cage Goes In Search Of A Bird (2010), won Production of the Year at the 2011 Life! Theatre Awards.

But Chong admits: "I think it's almost impossible to create a good piece of work in a non-hierarchical structure."

They tried to rely on consensus, but the collective eventually unravelled.

Still, he reiterates that it was a good experience for him and that he learnt a great deal.

For now, he will continue to pursue his growing interest in pared-down storytelling, reflected in Roots and the more recent Citizen Pig (2013), a comedic two-hander that looked at rental issues in Singapore. He took inspiration from The Coffin Is Too Big For The Hole, where the distractions of shock-and-awe multimedia effects are kept to a minimum.

He says with a smile: "I will still do what I'm doing right now - designing, writing, directing, acting - when the fire is still going."