Theatre director Elizabeth LeCompte, 70, sounds like she has her arms folded when she first picks up the telephone at her home in New York City.

Later in the interview, a genial warmth flickers to the surface. But for now, there is a certain guarded edge to her calm, articulate responses on theatre-making.

LeCompte is co-founder of the visionary Wooster Group, known for its radical adaptations of classic plays written by the likes of American greats Tennessee Williams and Eugene O'Neill, or William Shakespeare.

It splices these works with technology, a blend of the high-brow and low-brow, and experiments with genre and form.

I ask LeCompte what compels her to tackle canonical work, throwing out several terms from my mind's thesaurus: "rework", "strip down" - but when I blurt out "rearrange", she stiffens audibly. "I don't really rearrange. I'm drawn to try to do them."

She spells it out: "D-O, capital, DO them. To make them live, as they are written."

She continues: "I don't rearrange language. What I do is interrupt it. There are different places of rest and different places of speed. But the texts are in sequence... I'm quite classical that way, actually. People just think that my style is radical, that I have done something radical with the text."

You might say the same of the fiercely avant-garde American theatre company that LeCompte has led unflinchingly for nearly 40 years.

The Wooster Group will be coming to Singapore for the first time in September with Cry, Trojans! (Troilus & Cressida), a very interrupted version of Shakespeare's play of the same name. It will track the violent war between the Trojans and the Greeks, as well as the love story between its titular characters.

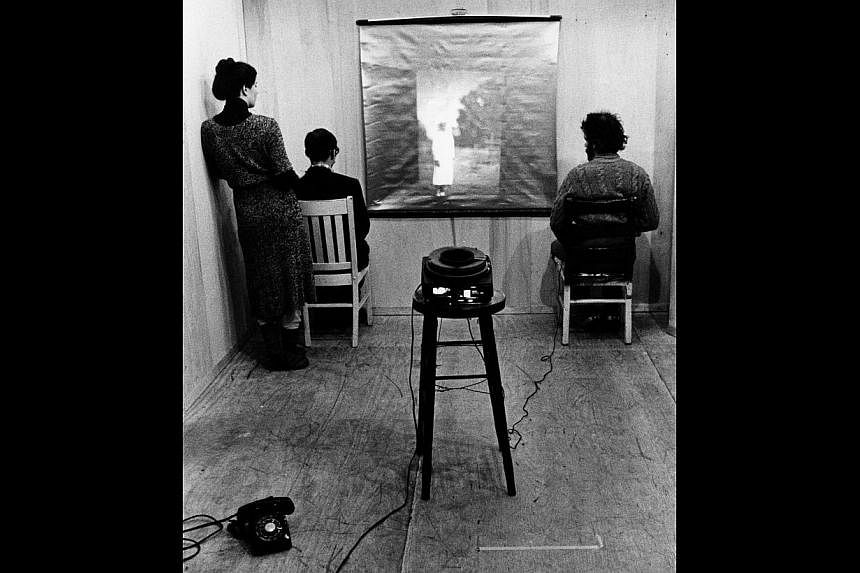

The Group has often stretched the boundaries of performance from its small performance space in New York City, The Performing Garage. LeCompte has always been staunchly uncompromising about her vision for her work, from controversially using blackface in performance in Route 1 & 9 (1981) and The Emperor Jones (1993 and 2006) to having her actors take drugs during the rehearsal process of L.S.D. (...Just The High Points...) (1984).

Here, she was curious as to whether artists could create while on LSD, or if the act of creation was a rational process. She videotaped the result of this experiment, and had the cast recreate their dialogue and movement on stage when no longer under the influence of acid.

This frenetic adaptation of The Crucible notoriously came under legal action from its playwright, Arthur Miller, and was eventually forced to close in January 1985.

LeCompte, often mentioned in the same breath as the vanguard of the American avant garde (the likes of Robert Wilson, Richard Foreman and Peter Sellars), continues to cut a powerful figure in the theatre world today.

She is largely private about her personal life. She was in a relationship with the late Wooster Group founding member Spalding Gray, whom she later left for another founding member, actor Willem Dafoe. They have a son and were together for more than 25 years, until a bitter parting in 2004. But she - and the Group - has weathered these heartbreaks.

I ask her how she managed to keep her romantic and professional life separate or if they inspired each other.

She says: "I don't have any answers for that. My whole life has been working with people that I've lived with. And it's worked out pretty well, on the whole."

She pauses. "I think any relationships are hard. I think that's a separate question. But working together - I've had very good 'working-together' relationships, all the way along.

"Frankly, for me, living outside of the Group is harder than making the work."

What were your first thoughts on how to tackle Troilus & Cressida? Was it perhaps an image, a sound or a line that inspired its shape?

I guess for our company and for us Americans, Shakespeare is a second language - and that's probably the case for a lot of English-speaking people now too. In some ways, it's so antiquated and written in a kind of verse that is not necessarily natural to the way we speak now.

We decided we really wanted to stay with the verse and that meant that we had to find a way as though it were a language we were learning, and it wasn't our native tongue.

That led us to images of Native Americans in American films - the way they speak when they speak English is a way of denoting that it's not their first language. Then we traced that to modern films made and performed by Native Americans.

There is still a way of speaking in the mid-west and upper mid-west that has a lilt to it, that echoes some of the early Native American speech patterns.

It seemed to fit the verse very well, so we took to using the motif of a Native American tribe, a fantastical tribe, that comes out of myths and stories... about what the Native American means in our history.

The work has travelled within the United States, but I'm curious about the reception when the piece goes out of the US, beyond the context where people are familiar with the Native American conflict.

I only hope that people are going to enjoy the piece, but I never plan on that (laughs). I have no idea - that's part of the reason we like to travel and show the work.

I like to work with a visual metaphor next to the words, so that if the words cannot be understood in a direct way... there is another track in the piece that you can follow: a visual, emotional, musical track that will take you on a journey.

Were reactions very different within the US?

We did previews of the show in New York and it was great - we had edited it into a new piece that was arranged around the story of Troilus and Cressida and the war that destroys everybody.

We "ghosted" some of the English parts. We performed them, but we performed them as though the Native American tribe is performing the parts of their enemies, and doing a mock war, telling the story within the tribe, with our people taking on the parts of their enemies. In New York, we had a wonderful time. We had a very good audience.

But in Los Angeles, we had trouble because we opened it there to the press, and it went out that we were using images from Native American culture, and that kind of politics is fraught in the US.

A lot of people say you can't play anything but your own self in theatre. You especially can't play a segment of the population that feels its identity is at risk.

It was very interesting. We had a lot of blowback about that, so we had to really talk with people and have forums after the show... And this is a very small part of our population, but they have the Internet, they don't see the pieces, they just hear about them. So when we come back to America and open it here, we will have that same problem. And it's a good one.

I think it's not the first time that The Wooster Group has looked at things in that way.

No. It's a constant battle. It's my battle to save theatre. (laughs)

How do you know when a work is ready, when it can be shown to an audience?

You don't. Sometimes I show them too early, sometimes I wait too long. You just do it by instinct and sometimes the instinct is dead-on for an audience, sometimes you're ahead of an audience or behind an audience. You don't really ever know and that's what's kind of fun about it - but it's also anxiety-producing.

What draws you to these classical and canonical works, wanting to make them live again? What's that impulse?

That's a pretty deep question. I just know I really like to make things in three dimensions on a stage. I like to see people move in a world that I've created. I like to imagine that the world actually exists as I'm watching it.

It's a place to go that's very stimulating for me. It's something that's lifted from everyday life, in a way, that puts me in a very high place. Sort of like a drug. But it's a healthy drug.

But at the same time, I've been looking at some of The Wooster Group's video blogs and I get the sense that everyday life is still very meaningful to the group as well.

Absolutely. We like to put it right next to the work we do on the stage. The two things kind of run in tandem.

I take a lot of impulses from the people I'm working with. I love to know about them, find out how they're doing.

Do you look at The Wooster Group as an ensemble or collective or do you see yourself helming a group of people? What's that relationship like between you and the members?

I really don't know. It changes with the people, it changes with the times. Because I'm directing the pieces, I have to take a certain helm in actually putting the piece together. But in the working phase, I try to leave that as loose as possible while still being at the helm, so that things can emerge from people that are unexpected for me.

And the people in the group change. I'm sure, if I look back, I'll see that I've picked projects according to who's in the company and what they're interested in.

Sometimes they're not interested in the things I'm interested in, and sometimes they leave me until I get it. And then I take over. We pass the baton a lot.

How do you take criticism, whether from critics or audience members? Do you find it helpful or do you just ignore it?

It depends on how it comes. Sometimes I'll take criticism - I made a piece of poor theatre and we asked everyone just to give us what they thought of the piece and what we should do differently, and we would try to implement one of the things that the audience had given us every night. Sometimes we do that.

Sometimes I just have to disregard it because I can't work with that kind of pressure, so I just don't engage.

Sometimes when a piece hasn't been done for a while, I go back after 10 years or so, and I read reviews and go, "Oh my God, how did we make it through that?"

Our early work was... a lot of times, very negatively reviewed. A lot of times I just have to skip over it and come back to it later.

Do you think part of it is due to the Group always being just ahead of the curve, ahead of what people expect?

Yes, I think we have a tendency to do that.

Because we're working where it doesn't have to be a success the first time round. So we are able to stretch things where other people in theatre are not.

We are more like writers and even film-makers, where a person can say, oh yes, this got a bad review, but 10 years later, it's the cult hit of the century.

In theatre, it's very hard to do that because you have to succeed right away. For us, we don't have to because I can bring it back. I have five or six pieces in repertory now that I could bring back at any time. And usually when they're re-reviewed, they're re-reviewed with a little more understanding of where we are coming from.

What keeps you awake at night?

Sometimes I get - I can't remember what they're called, but it's a physical thing in your legs as you get older? Cramps! Cramps. I have to get up and walk them out. So that keeps me awake.

Or sometimes if I have to do something very important early in the morning, I worry that I'll miss the alarm. That keeps me awake.

When I'm working on something, sometimes I'll stay awake thinking about how I can work on it. But in the past couple of years, I've stopped doing that. Because I realise that I can work it out in my brain, but when I bring it into the company, it's the company that has to work it out. So that's changed.

What helps you get up in the morning?

I just do it naturally. Light. I love light. I see the light and I get really excited. And I think, "Oh my God!"

And I get excited and I think, I'm going to make a cup of coffee and then I'm going to read the paper. That gets me up in the morning. I'm a morning person.