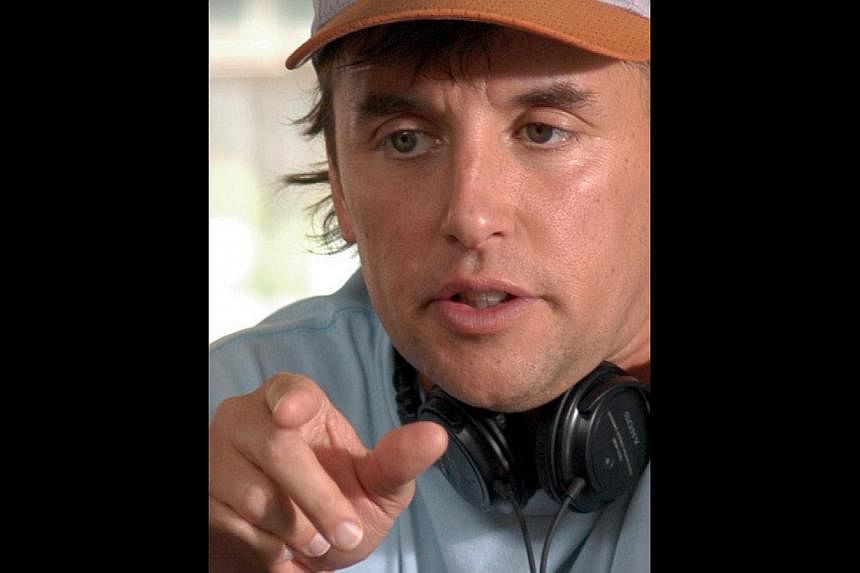

Art is long and time is fleeting, so says the 19th-century American poet Henry Longfellow. It is a sentiment American film-maker Richard Linklater would no doubt agree with. The School Of Rock director is back in cinemas with Boyhood, a critically acclaimed film that was 12 years in the making.

The film charts the development of a boy called Mason from the age of six to 18 and he is played by Ellar Coltrane, as the hitherto unknown actor grew up in real life. There is no conventional narrative propelling the story.

Rather, the audience simply watches a boy grow up into a man, witnessing his first love, his new schools and his alcoholic stepfathers. He has a loving but befuddled mother and a cool if mostly irresponsible father.

Linklater, 54, says: "Boyhood almost didn't feel like a film at all while we were working on it. It didn't have all the usual expectations. It felt more like a novel or a time sculpture. Cinema is my world, but it did feel 'other', like it was in its own cinematic universe."

Recalling how a few weeks before this London interview he was showing his daughter some films by Auguste and Louis Lumiere, the French brothers who are widely regarded as the first filmmakers, he adds: "I think cinema can depict normal things. It was just people walking out of a factory. They were just recording life. It's pretty magical, the fundamentals of cinema. You could feel the film-makers' excitement."

He started preparing Boyhood in 2001, before shooting School Of Rock (2003), and recruited his friend and regular collaborator Ethan Hawke to play Mason's wayward father.

Patricia Arquette, meanwhile, stars as Mason's mother, while Linklater's own daughter, Lorelei, features as the boy's sister.

Rather than a conventional screenplay, Linklater worked with a structural blueprint. His actors and crew gathered every year, whenever their schedules permitted, for short and intense shoots lasting three or four days. He would then write and edit along the way, chatting to his young star and his adult actors about specific chapters in their lives, which he would then incorporate into his story.

"I knew the last shot of the movie in the second or third year. I knew where it was going. I knew the structure," he explains. "Normally, when you make a film, you get to think about it all, but once you are shooting you have to think on your feet. You simply don't have much time.

"This is the opposite. You put in a lot of thought, shoot for three days and then have a year to think what's next and to tell the actors, 'Hey, next year we are going to be doing this, so let's start talking about that.'"

In some years, they filmed twice and there was the occasional year when they did not film at all. "Each shoot was usually between six and eight months and a year or 16 months," says Linklater. "There was no standard."

In truth, nothing about the film-maker is standard. He emerged at the forefront of the United States renaissance in independent cinema in the early 1990s.

His second film, the Sundance festival favourite Slacker (1991), a study of youth culture, lent its name to a whole new genre.

Since then, his films have varied widely, ranging from the likes of high school comedy Dazed And Confused (1993) and French-inspired talkie romance Before Sunrise (1995) to sci-fi animation drama A Scanner Darkly (2006) and dark comedy Bernie (2011).

If there is a common thread that runs through his rich and diverse career, it is his fascination with time, something which he calls "the essence of cinema".

He says: "I think it's a unique property to film. It is the clay of cinema - if it were a sculpture - or the paint. It is so innate that you don't even think about it."

This quality is pronounced in a number of his films. His earliest offerings, such as Slacker and the semi- autobiographical follow-up Dazed And Confused, are set within the confines of a single day, while high-school drama Tape (2001) plays out in real time.

Then there is the trilogy he shot with actors Julie Delpy and Hawke: Before Sunrise, Before Sunset (2004) and Before Midnight (2013) which return to the same characters, Celine and Jesse, charting time's effects on love and life.

"Boyhood in a strange way affects Before Sunset and Before Midnight," says Linklater. "This film affected them more than they affected it, because this preceded them. This film helped us to take that scary leap into going back and revisiting the characters from Before Sunrise.

"The notion of a life project probably made it a little easier to do Sunset and Midnight," he adds.

"Boyhood, we were committed to. Those were optional. We didn't have to revisit them. Boyhood, to make it work, we knew we had to do it for 12 years."

Thus far, Boyhood has taken more than US$10 million (S$12.5 million) at the worldwide box office, which is a reasonable return, and has wowed critics. It has a 99 per cent approval rating on the review aggregating website Rotten Tomatoes, while the Washington Post claimed that "Boyhood isn't just a masterpiece. It's a miracle".

Indeed, such is the positive feedback, the Hollywood Reporter says that Linklater has dropped out of filming The Incredible Mr Limpet, a remake of a 1964 film, to complete another personal project, That's What I'm Talking About.

Returning to familiar ground for Linklater, the film is something akin to a Dazed And Confused sequel, set on a 1980s university campus and revolving around the trials and tribulations of a group of friends trying to make it onto the baseball team.

"When I think of new areas of storytelling that I am excited about in cinematic, narrative forms, I find most of my ideas that push those boundaries have to do with time and how time is treated," he says.

"Time is powerful. And in relation to our world and ourselves, the selves we have been in our lives - that has everything to do with time. I focus on what I feel is the reality of our perceptions in this world, and I want to try to tell stories about that, to whatever degree."

Boyhood opens in Singapore tomorrow.