Dutch artist-inventor Daan Roosegaarde has quite an obsession with smog and walks around with a packet of sooty particles in his suit jacket.

He pulls it out of his pocket to show The Straits Times what people in Beijing, a heavily polluted city, inhale daily.

The 37-year-old says: "It's really disgusting. This is inside our lungs.

"Someone, somewhere, decided this was a good idea," he declares sardonically.

He thinks about smog often and rattles off information about its deadly, choking effects.

If he seems fixated with dirty air, that is because his name has become somewhat synonymous with ridding cities of smog.

He and his team of designers and experts at Studio Roosegaarde - with offices in Rotterdam and Shanghai - are the driving force behind the Smog Free Project.

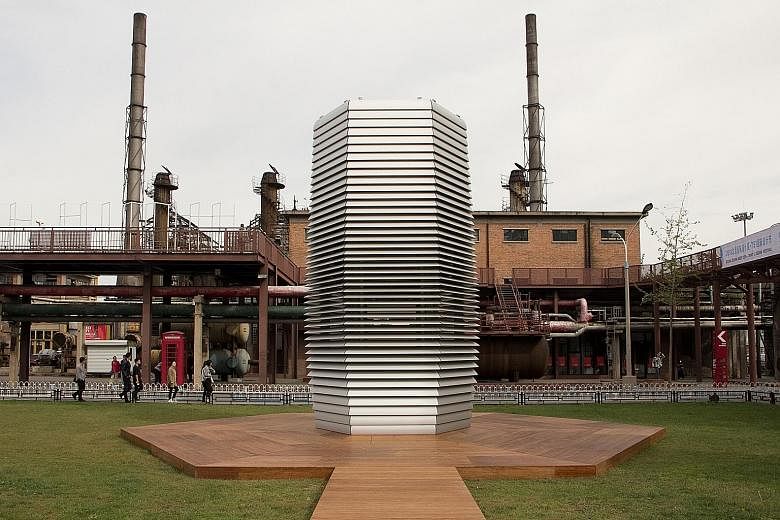

They created a 7m-tall Smog Free Tower, which has been dubbed the biggest air purifier in the world. Polluted air is sucked in at the top and purified air is released through vents on its sides.

Studio Roosegaarde also worked on the tower with Mr Bob Ursem, scientific director of the Botanic Garden at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, who has patented inventions for collecting fine dust and ultra-fine dust.

The lightweight aluminium machine runs on wind energy and uses no more electricity than a 1,400-watt water boiler.

The tower made its debut in Rotterdam in 2015.

Last year, it travelled to Beijing and was set up at 751 D-Park in the 798 Art Zone, an art and design district in the Chinese capital.

Mr Roosegaarde says the tower can clean 30,000 cubic metres of air in an hour and collects more than 75 per cent of two kinds of pollutants - PM2.5 and PM10 smog particles.

Removing pollutants in the air is a great idea, but selling the experimental concept of a giant smog vacuum cleaner still took a bit of effort.

Mr Roosegaarde says: "It's innovation, so everyone had to get used to it in the beginning."

He adds that the tower has since caught on and that Beijingers "lovingly call it the 'clear air temple'". The Smog Free Tower will now tour other parts of China. The new location will be announced next month.

Beijing was the inspiration for this project. While on a trip to the cityin 2013, Mr Roosegaarde could not see anything outside his hotel room window, no thanks to the smog.

Last year, the World Health Organization named China as the world's deadliest country for outdoor air pollution. It reported that more than one million people died from dirty air in China in 2012.

"It's a real problem for the city," Mr Roosegaarde says, explaining the shift in Chinese attitudes, as the country fights pollution hard now.

Mr Roosegaarde, who founded his studio in 2007, adds: "It's not something you make fun of or take lightly. It's an intense topic and people want to do something about it. What's the alternative? Do nothing? That's not possible."

He boldly went to the global online community to ask for financial backing. He began a Kickstarter campaign in 2015, offering rings, cuff links and souvenir cubes as incentives for backers who funded his idea to build the tower. The chunky pieces feature compressed, filtered smog particles, encased in a cube.

A total of 1,577 people pledged €113,153 ($170,660) - more than twice the amount of his €50,000 goal. His studio declined to reveal the cost of the tower.

Today, he talks about the project with confidence, but says getting the approval of netizens scared him.

"Why would anyone want to pay for waste on their finger? But as the project took off, I realised that people want to be part of the solution, not just causing the problem."

The Smog Free Project is not a fleeting obsession of a flighty artist.

From his body of work, it is clear that Mr Roosegaarde is passionate about the environment and wants to spur change in a beautiful way.

To raise awareness of rising water levels, he created Waterlicht in 2015 for the Dutch District Water Board Rijn & IJssel, a Dutch organisation that manages water bodies in some municipalities.

The dreamy LED light installation of wave-like blue rays was meant to show how the Netherlands would look like if it was submerged.

Then there was the stunning glow-in-the-dark bike path inspired by Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh's The Starry Night. The path, in the Dutch county of Brabant, functioned on solar power. It opened in 2014.

When he was Singapore, he spoke to officials about the possibility of developing a light-emitting bicycle path, though details are not confirmed.

Commissioned work is how he sustains his studio. But he also "spends (his own) money, time and energy" to create things he is interested in.

He concedes that some people may dismiss his environmental messaging, given the pretty packaging and his artist tag.

But Mr Roosegaarde, who was trained in fine arts and graduated from The Berlage Institute in the Netherlands with a master's in architecture, says: "Labels are a way for people to reject ideas. A lot of people have told me what I want to do can't be done.

"But it's my job to prove them wrong," says the son of teachers.

The next problem he wants to tackle is out of this world, literally: clearing space waste.

He estimates that there are 1.2 million man-made objects, each larger than 2cm, floating in outer space. These include broken pieces of satellites.

He says if the debris hit a satellite, services such as Facebook and banking go down.

With a chuckle, he says that all he needs to get started is just €8 million and a non-cloudy night for a prototype.

While the bachelor is pleased that his projects have made an impact around the world, he is not flattered that some of his works have also been copied. It is not that he is protective of his ideas. Rather, he feels that the copycats should have improved the concepts.

"I wish they would upgrade it," he says with a tinge of annoyance.

"I already did Chapter One. If they improved it, I would appreciate that. No one owns an idea. But pick it up and make it better.

"If it's a cheap rip-off to save a couple of bucks, then there's no evolution or progress."

Natasha Ann Zachariah

WATERLICHT

On a cold February night two years ago, a "virtual flood" of wavy, electric-blue lines of LED light flowed freely above a flood channel near Westervoort, a town in eastern Netherlands. But Mr Daan Roosegaarde's ethereal light installation, named Waterlicht or Waterlight in English, was not put on just to recreate the beautiful glow of Northern Lights. It was intentionally displayed near the banks of the river IJssel to remind visitors that levees prevent the river from overflowing. The blue lights were meant to make visitors feel like they were underwater.

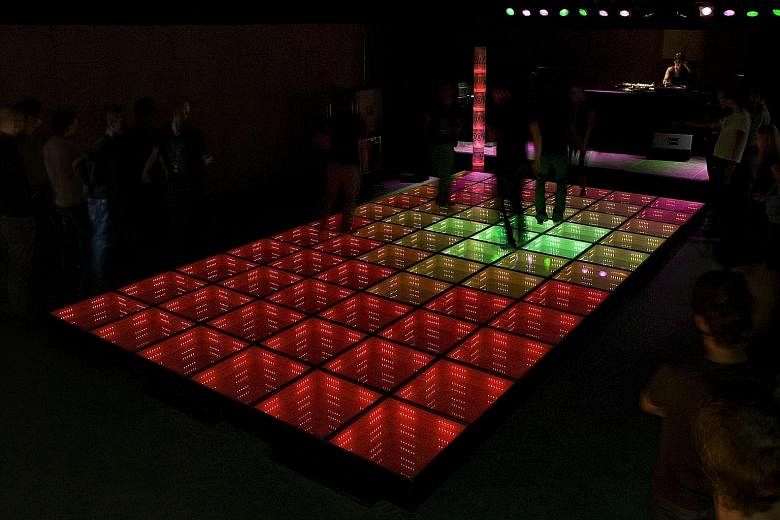

SUSTAINABLE DANCE FLOOR

In 2008, Mr Roosegaarde's Studio Roosegaarde created a dance floor that lit up when clubbers pranced around and powered the LED lights set in it. Their feet generated electricity through an electro- magnetic generator planted under the floor. The dance floor was installed in Club Watt in Rotterdam.

VAN GOGH-ROOSEGAARDE PATH

Inspired by Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh's famous work, The Starry Night, Mr Roosegaarde designed a 1km bicycle path embedded with glowing fragments.

Studio Roosegaarde worked with Heijmans, an European construction firm, on the path. It was opened to mark the start of the Van Gogh 2015 international theme year.

Design websites and media outlets noted that the path's glowing aura comes from the stone fragments that trap solar energy gathered during the day and emit light at night.

The path is part of the Van Gogh cycle route in Brabant, the Dutch county where the artist was born.