NEW YORK • You get back to Eden by preserving what exists of the original or by creating new versions of your own.

Roberto Burle Marx, the Brazilian landscape architect, did both.

From the 1930s, mainly in South America, he designed some of the modern world's most distinctive parks and gardens, from an immense, jazzy tattoo of a promenade on the Rio de Janeiro beachfront to rooftop plantings in a city carved overnight from jungle, Brasilia.

In the process, he became deeply invested in saving the Amazonian paradise that surrounded him; fought to halt its devastation; and turned his home near Rio into a botanical rescue farm, a sanctuary for one of the world's largest collections of tropical plants.

Despite this ecological pioneering, his name, though monumental in Brazil, is not widely known in New York.

The last New York survey of his career was in 1991, at the Museum of Modern Art, and it seems not to have attracted wide notice.

Roberto Burle Marx: Brazilian Modernist, on till Sept 18 at New York's Jewish Museum, deserves a wide audience. It is a lovely and eye-opening show, demonstrating that his aesthetic contributions went beyond plantings.

He created mural-size decorative wall coverings from ceramic tiles; wall reliefs carved in wood and stone; and immense wool tapestries, one of which takes up an entire wall in this exhibition's main gallery. It also suggests that this artist, who died in 1994, has finally found his proper global context in an environmentally activist moment that he, long ago, helped create.

He was born in 1909 in Sao Paulo into a cosmopolitan family. His merchant father was a German-Jewish immigrant, his upper-class mother a Brazilian Roman Catholic.

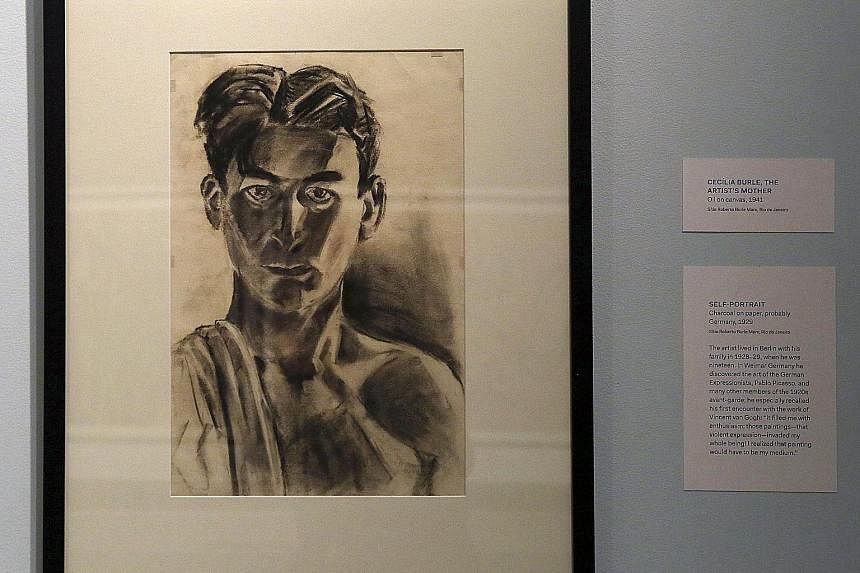

When he was 19, he spent a year in Berlin soaking up Picasso, German expressionism and van Gogh's electric landscapes, the influence of which he would carry back to South America.

In Berlin, he also saw, as if for the first time, the native flora of his homeland, displayed as exotic imports in that city's botanical museum. He already had some knowledge of European-style horticulture through his mother. But once back in Brazil and studying painting at the National School of Fine Arts in Rio, he turned his attention to local plants.

His interests in art and botany merged in 1932 when one of his teachers, Lucio Costa, the modernist architect and future planner of Brasilia, got him a gig designing a garden for a private home.

Within two years, he was director of parks and gardens in Recife, his mother's home city. By 1938, he was taking on major private and public jobs, among them a reputation- making commission for the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio.

For him, painting and landscape design were inseparable, if not identical, art forms: He spoke of design as a way of painting with vegetation, but acknowledged its distinguishing dimensions, which encompassed touch, sound, fragrance and change with the passage of time.

In this show, visitors see him developing his thinking about this.

A 1935 pencil study for a Recife garden is an academically correct perspectival view of leafy trees lined up along a large pool, with nothing particularly Brazilian in sight except a distant stand of palm trees.

Three years later, in a large, light-touch Matisse-like ink drawing, viewers are in a lush grove of monster philodendron leaves with a bevy of tiny female nudes.

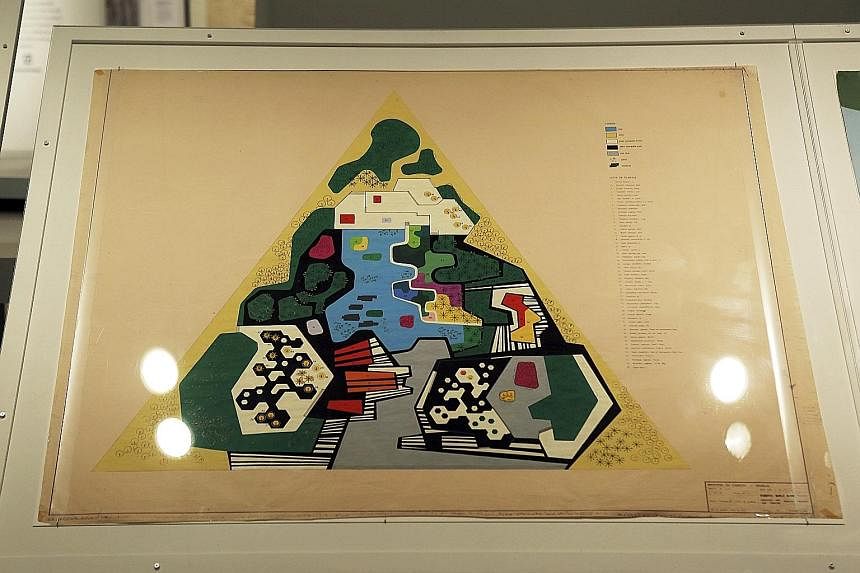

Then, with his plans for the Ministry of Education and Health roof garden, comes the revolution. The building was designed by Costa, assisted by the young Oscar Niemeyer, and with no less an eminence than Le Corbusier on tap for advice.

Burle Marx rose brilliantly to the occasion, producing a garden of entirely indigenous vegetation set in beds bulging with biomorphic curves. The high-colour gouache study for his plan could pass purely as an abstract painting in the manner of Jean Arp or Miro.

One of Burle Marx's most celebrated projects is the 4km thoroughfare, Avenida Atlantica, which he designed in 1970 for the Copacabana shoreline in Rio.

An unfurling crazy-quilt of rolling, twisting abstract patterning picked out in white, black and brick-brown paving stones, it is not his most original concept.

The idea is based on Portuguese models. But it is the one that perhaps most fully achieves his long-stated goals of visually activating public space and of giving pleasure to the maximum number of people. You do not walk the promenade, you dance it - its visual rhythms have a samba beat.

Ultimately, the garden he may have cared about most was his own, a landscape accumulated, rather than specially composed, at his home on an old plantation outside Rio. Donated by the artist to the Brazilian government and now known as Sitio Roberto Burle Marx, the garden blends elements from past projects: reflecting pools, fountains, clumps of jungle, thickets of shrubbery harbouring wildlife and multi-colour patchworks of ornamental grasses.

The estate is home, outdoors and in vast greenhouses, to more than 3,500 plant species, most indigenous, about 50 of them discovered by the artist on his repeated, and increasingly anguished, research trips to the Amazonian rain forest.

Sitio may be his real monument. It is certainly the most personal of his many preserved and constructed Edens.

It is what paradise should be: infinity found in enclosure, embodying a vision of nature guided by two feelings, once described by Burle Marx as "the love that drives us and the humility that corrects us".

NEW YORK TIMES

•Roberto Burle Marx: Brazilian Modernist is on at New York's Jewish Museum till Sept 18.