One night in Kuala Lumpur two months ago, I took my mother out for dinner.

We went to Fatty Mok Hakka Yong Tau Foo in Salak South Garden, where she lived for the last 40 years. Between us, we polished off 15 pieces of yong tau foo; mum had a bowl of noodles to boot.

Then I drove her to a dessert cafe in a neighbouring estate. Both of us ordered almond milk. I took a picture as she happily tucked into hers. When I showed it to her, she grimaced and said she looked ugly but allowed me to upload it on Facebook. I captioned it: "Just me, mum and our favourite dessert."

I saw her again three weeks later, under much sadder circumstances. She was in hospital and I had to sign the consent forms for her to undergo an operation.

A few days earlier, she had been besieged by an intense pain in her stomach. A couple of visits to the GP and her favourite sinseh did not help, so one of my cousins drove her to Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia where doctors did an X-ray and immediately warded her.

A CT scan the next day revealed a tumour in her intestines, causing blockage of the colon. Like all women of her generation, my 82-year-old mother hated hospitals and had an abject fear of operations.

My siblings and relatives rallied around her, told her to be brave and assured her everything would be okay. I tried to make her laugh by cracking a joke about going under general anaesthetic.

"When you wake up, it's like being 'sat on' by a ghost," I said, using the Chinese euphemism to describe spirits entering the body. "You're aware of what's happening but you won't be able to speak or move, so don't panic."

She smiled but I sensed her fear, just as she sensed mine.

The surgeon's face was grim when she emerged from the operation which took nearly four hours.

Sitting me down in a quiet corner, she told me the tumour was a nasty one. It looked as though it had been there for a while, and was touching her spleen, diaphragm and kidney. It was also sitting on some major arteries - touching it would probably result in massive bleeding.

The surgeon said she built a bypass so my mother could eat and not have to wear a colostomy bag. "Hopefully, she will have some quality of life in the remaining time that she has," she says.

My mother was given six months.

I struggled to calm the myriad emotions battering my core and process the herd of wildly divergent thoughts galloping in my head. How can this be? How do I tell mum? Do I tell her? How do we look after her? How many months should I take off from work to spend with her? Will she suffer?

The questions were not new to me. They had popped into my head regularly for some years now, probably ever since my father died 20 years ago. But I had always refused to answer them because they were just too dreadful and painful to contemplate. But now this most awful of mid-life passage was staring me in the face.

I was not alone. Apparently the 900,000 baby boomers - those born between 1946 and 1964, a cohort to which I belong - in Singapore are losing about 30 parents every day.

It is sad it sometimes takes a crisis to bring out our better side.

Over the next few days, I did things which I wished I had done more of when she was hale and hearty: feeding her, holding her hand, massaging her feet, stroking her brow and comforting her.

My mother did not make the six months. Six days after she had the operation, she developed complications and had to have a second operation. The tumour, silent all this while, had now decided to go on a rampage, abusing all her organs.

She was under heavy sedation when she was wheeled out of the operation theatre into the intensive care unit. The prognosis was bleak - she could go anytime.

"She may not be conscious but talk to her. I can't explain it, but trust me, she knows," the surgeon told us. Close friends who have lost their parents told me the same thing.

Over the next two days, my siblings and other family members took turns to be at her side.

Once a strong woman who lived through the war and toiled for decades as a washerwoman and cook to bring up four children, she was now just a frail wisp of a woman hooked up to drips and machines. I've never felt so heartbroken, lost and fearful at the same time.

"Thank you" and "I love you" - phrases which seemed so corny and hard to utter when all was hunky-dory - tumbled out almost desperately in my time with her.

Two days after the second operation, she died peacefully. All her children were with her, so were most of her siblings - she was the eldest of five - and many of their children.

All of us were immensely sad but also very thankful she was spared prolonged pain and suffering.

Maybe mum had it all worked out. After all, her favourite refrain when she was alive was: "When I go, I want it to be quick. I don't want to be a burden to anyone."

For her wake, we all contributed our favourite photographs of her which one of my cousins compiled into a montage and played on a TV screen.

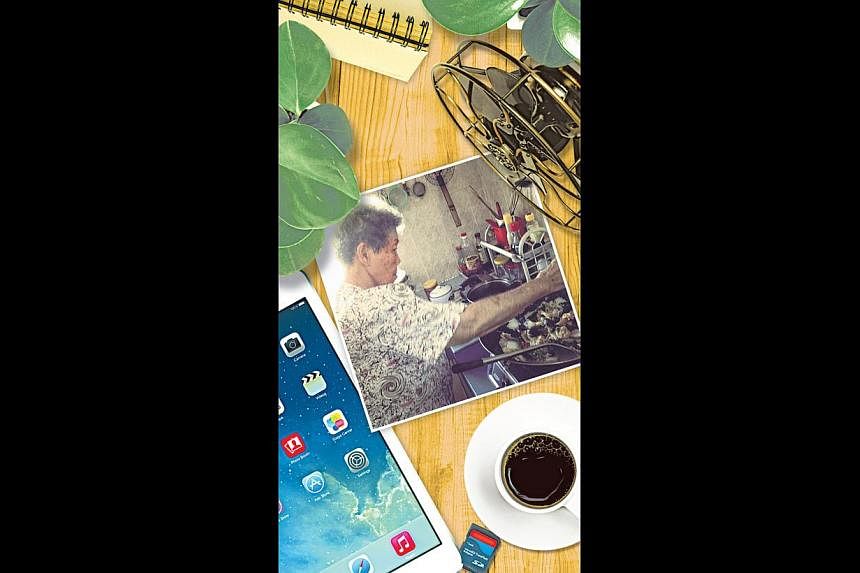

I gave two of my favourites: one of her in a Darth Vader mask, with her arm in a sling (taken two years ago when she was here on a visit and broke her arm), and one of her in her kitchen, slaving over her legendary Chinese New Year jai choi, a vegetarian dish.

A friend who flew in from Dubai to pay his respects said he was envious at how closely knit we were as a family and how my mother seemed to be a central figure in the clan.

He was right. Like my grandma before her, she was a Cantonese matriarch, a great cook at whose home one could always find a nourishing bowl of soup and a feast every time there was a festival or a celebration.

One week after she left us, a dozen family members congregated at her house for a feast. We decided to take all the ingredients we found in her two fridges, including mushrooms and abalone, shop for more and cook up some of the dishes for which she was well-known.

My second aunt made a lotus root soup, my cousin did her jai choi, my sister stewed the mushrooms and abalone and made a prawn omelette, and I braised some pork. My brother-in-law bought several durians, one of my mother's favourite fruits.

Some of the dishes lacked her touch, but I know if mum saw us noisily tucking in at her dining table, she would have smiled.