For veteran Peranakan chef Jolly Wee, childhood games of masak masak, or makebelieve cooking, involved real food.

When he was about 10, he built a makeshift brick stove in the back alley of his family's terrace house in Joo Chiat, using foraged dry coconut leaves for kindling. The children in the neighbourhood came to sample the rice that he cooked in a cigarette tin.

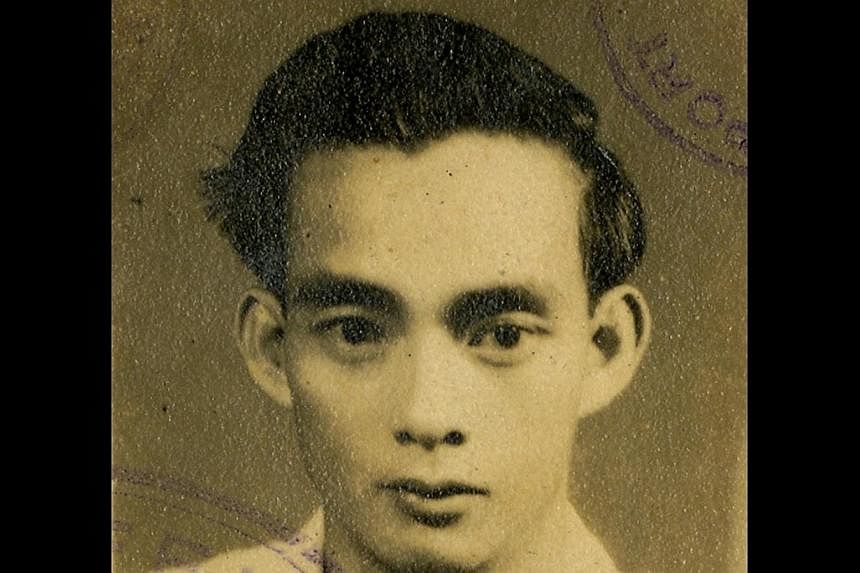

"That was how I became interested in cooking. I'd learnt cooking through trial and error from my mother, from observing her in the kitchen. She encouraged me," says Mr Wee, 87, whose six children include Dennis, chairman of real estate agency Dennis Wee Group (DWG), and Mervin, managing director of the Jean Yip Group that operates hair and beauty salons. Mr Jolly Wee's wife, Violet, died of stomach cancer two years ago at the age of 81.

The Peranakan community harks back several centuries to traders from China who married local women and made their home in the British-controlled Straits Settlements of Singapore, Penang and Malacca. A Peranakan or Straits-Chinese man is called a Baba and a woman, a Nonya. Peranakan cuisine has strong Malay and Indonesian influences, in its use of rempah or spices, for instance.

In a career that has spanned more than 60 years, Baba Jolly, as he is also known, has taken his culinary skills to places such as San Francisco, Abu Dhabi, Borneo and Bali.

He has promoted Peranakan cuisine at local and foreign hotels and at food festivals overseas, where he represented Singapore. Sharing his recipes freely, He has also helped set up Peranakan restaurants and taught cooking classes. His recipes have been published in newspapers and other media over the years.

His mother, housewife Tan Ah Neo, started teaching Jolly, the eldest of her six children, to cook dishes such as assam pedas, a sour and spicy fish dish, when he was 10 years old. Later, during the Japanese Occupation in Singapore, he learnt to cook the ubiquitous wartime food, tapioca, in coconut gravy. She sometimes gave him 10 cents to buy groceries from the market.

Once, his mother was too squeamish to slaughter live poultry for their Chinese New Year meal and the boy had a go. The chicken was "still walking" before he despatched it on his second attempt.

The first meal he made for his family was yellowtail fish, dipped in flour and deep-fried, and sweet potato and vegetables cooked with coconut milk.

Mum would go out to play cherki, a Nonya card game, and "by the time my father, who was a postmaster, came back from work, I would have the food ready on the table", Mr Wee recalls.

In primary school, he helped Madam Tan when she worked as a roving hawker, selling kueh or desserts and other goodies.

"I would shout, 'popiah goreng, curry puff'! I gained experience in selling food," says Mr Wee.

He later followed his mother's example, selling mee siam and laksa in similar fashion in St Michael's Estate, with his only daughter, Sylvia, in tow, lugging a foldable table. Then a teenager and now a 64-year-old housewife, Sylvia says her father has handed down all his recipes to her.

During World War II, Mr Wee was issuing food rations at a shop selling toddy, an alcoholic drink, in Katong when a girl on a bicycle caught his eye.

The girl, Violet, broke the ice by asking to borrow his camera. He and Violet, a Hakka Chinese, started cycling together.

The young couple soon found themselves in star-crossed circumstances. Both fathers wanted to marry off their child to someone else.

"I saw Violet's father slap her after she went out with me. I was very angry. I made a plan. We packed our things, just a few clothes and ran away together. That was how our life began," says Mr Wee, who was about 20 at the time.

Helped by a Malay woman he knew, Mr Wee secured a room in Dickson Road that was half the size of the hall in his three-room HDB flat in Toa Payoh, where he now lives alone with a domestic helper, Suwati.

Today, his children are regular visitors and Sylvia drops by almost every day. When Life! visits him at his home, Sylvia, Dennis, Mervin, Bernard, who is a 53-year-old hair salon owner, and Dennis' wife Priska came by "to support him", in Dennis' words. The interview is transformed into a chatter-filled opportunity for lunch and "lau-jiet", a dialect term for enjoying life. One of Mr Jolly Wee's sons, David, lives in Vietnam, and another son, Alan, died at 17 in 1972 in a road accident.

After the elopement, Mr Wee's mother tracked the pair down and supported them by giving them some money.

The rift with his father was mended only when the couple, who had registered their marriage, returned home about a year later.

"I brought our newborn, Sylvia, and showed her to my father. He cried. I also cried. From then on, we became closer. He forgave me," says Mr Wee.

The family celebrated, complete with a traditional tok panjang or a long table of food.

In his early 20s, Mr Wee, who says he has an adventurous streak, went to sea as a steward on board passenger ships of the Blue Funnel Line, where he eventually became a chef.

After about two years, he ran a Japanese-owned oil-rig camp in Abu Dhabi. That was followed by a stint running a similar camp in Balikpapan, Borneo.

The Japanese, Middle Eastern and Iban workers he encountered appreciated the food he served at these camps, including satay and babi pongteh, a Nonya braised pork dish, because he took the trouble to "understand the local palate", says Mr Wee, adding that he found favour with a feared Iban chief in Borneo, who was covered in tattoos and known for his tribal practice of headhunting.

He turned down the spice level for foreign clients, which he also did later in pre-euro Germany, where he sold chicken curry in Hanover for two deutsche marks a cup, while promoting Singaporean cuisine there on an official visit.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, he ran a business supplying Western and local food to cafeterias in factories in Singapore. His high-profile sons, Mervin and Dennis, learnt to cook from him.

Mervin, 56, who is married to Ms Jean Yip of Jean Yip Group, started working with his father in this canteen business around the age of 14.

"My father would wake up at 3 or 4am to go to the market. I learnt the importance of discipline, hard work, integrity and passion," says Mervin.

"He ran more than 20 canteens over 12 years in companies like Texas Instruments, Mobil, Caltex and General Electric. I took care of one or two canteens, which gave me an idea of how to run a business."

Mervin's elder brother, real estate chief Dennis, 63, who cooks a mean Hokkien Mee and once put on a Superman outfit in a property advertisement, says his father taught him how to be creative in business.

His father is conscious of his image, adds Mervin. Mr Wee has his hair coloured jet-black at a Jean Yip salon and his cologne of choice is Brut.

After leaving the canteen trade, Mr Wee gradually became known as an authority on Peranakan food, for example, via the cooking promotions he spearheaded at different hotels, including Hotel New Otani.

Ms Patricia Lee, founder of the Chilli Padi Peranakan food business, was a protege of Mr Wee. After taking a cooking class he taught, Ms Lee, who is not a Nonya, invited him to be a consultant when she set up Chilli Padi Nonya Restaurant in Kim Tian Road in 1997.

He was a stern taskmaster and a stickler for getting traditional recipes right.

"He disciplined me very strictly - I used to cry. When the cooking was not up to his standard, he scolded me," says Ms Lee. For instance, Mr Wee insisted on having a particular texture for ayam buah keluak, a signature Peranakan dish of chicken braised in a tamarind gravy with buah keluak nuts.

She says she was able to expand Chilli Padi, which now has a major catering arm and 180 staff, because Mr Wee, whose recipes her restaurant's menu was initially based on, pushed her hard.

Mr Wee says his tear-wringing, slave-driver approach was because "when I teach a person, I really make an attempt to make the enterprise succeed". He once walked out on an eatery he worked with. It had changed his recipes, compromising on the taste of the cooking.

One of his successes in old age has been revitalising Spices Cafe in Concorde Hotel Singapore. During his first visit there, around 2008, he says he found only one customer at the cafe during lunch.

Tasked with promoting Peranakan food there, Mr Wee brought in Peranakans familiar with the Baba Jolly name, which he leveraged for marketing in newspaper advertisements and through word of mouth. He also suggested setting up an adjacent stall, which today still sells Peranakan porcelain ware and traditional baju kurong garments. On a lunch-time visit last week, the cafe was almost full and buzzing.

Mr Andrew Khoo, vice-president of operations at HPL Hotels and Resorts, worked with him on rebranding Spices Cafe about seven years ago.

"Baba Jolly Wee was responsible for the menu and training the staff. He was so meticulous in taste and presentation. He was adamant that the buffet table should be decorated with ingredients like blue ginger, which he wanted the younger generation to appreciate," says Mr Khoo, adding that he remembers Mr Wee "screaming his lungs out" at a staff member who had taken a short cut in the cooking.

"He is like one of the old masters, it's got to be done in the proper way. Sweating onions, for example. If they are not translucent and you hurry and add the other ingredients, the flavours are not there.

"In his own way, he has been pushing the envelope in making people appreciate what Peranakan food is about, teaching young people and bringing them into the fold. His legacy is in ensuring its authentic taste," says Mr Khoo, describing Mr Wee as "one of the pioneers who passed on his knowledge".

For Peranakan food doyenne Violet Oon, who invited him to participate in the Singapore Food Festival in 2009, Mr Wee is "one of the bridges between the past and the future" for Peranakan cuisine.

"To a certain extent, the younger talents, who are more savvy, get showcased more. There's so much celebration of youth that people forget our living treasures. He's part of the generation that needs to be honoured."

Mr Khoo adds: "Mr Wee is so generous with his recipes. I once asked him, 'Aren't you afraid of sharing your recipes?' He said, 'At the end of the day, the trick is managing the fire. You must know how to bring the fire down.'"

Mastering cooking temperatures was easy for Mr Wee, who cooked with firewood as a child. The patriarch, who has 11 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, knows a good chef is more than the sum of his recipes.

He says: "In the early days, when you take some shallots in your hand, it's about 110g. Recipes can be given to everybody, it depends on your own hand, how you cook and how you measure."