Behind Lucky Peach's closing, founders' visions collided

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Lucky Peach has 30,000 print subscribers and has published 22 issues.

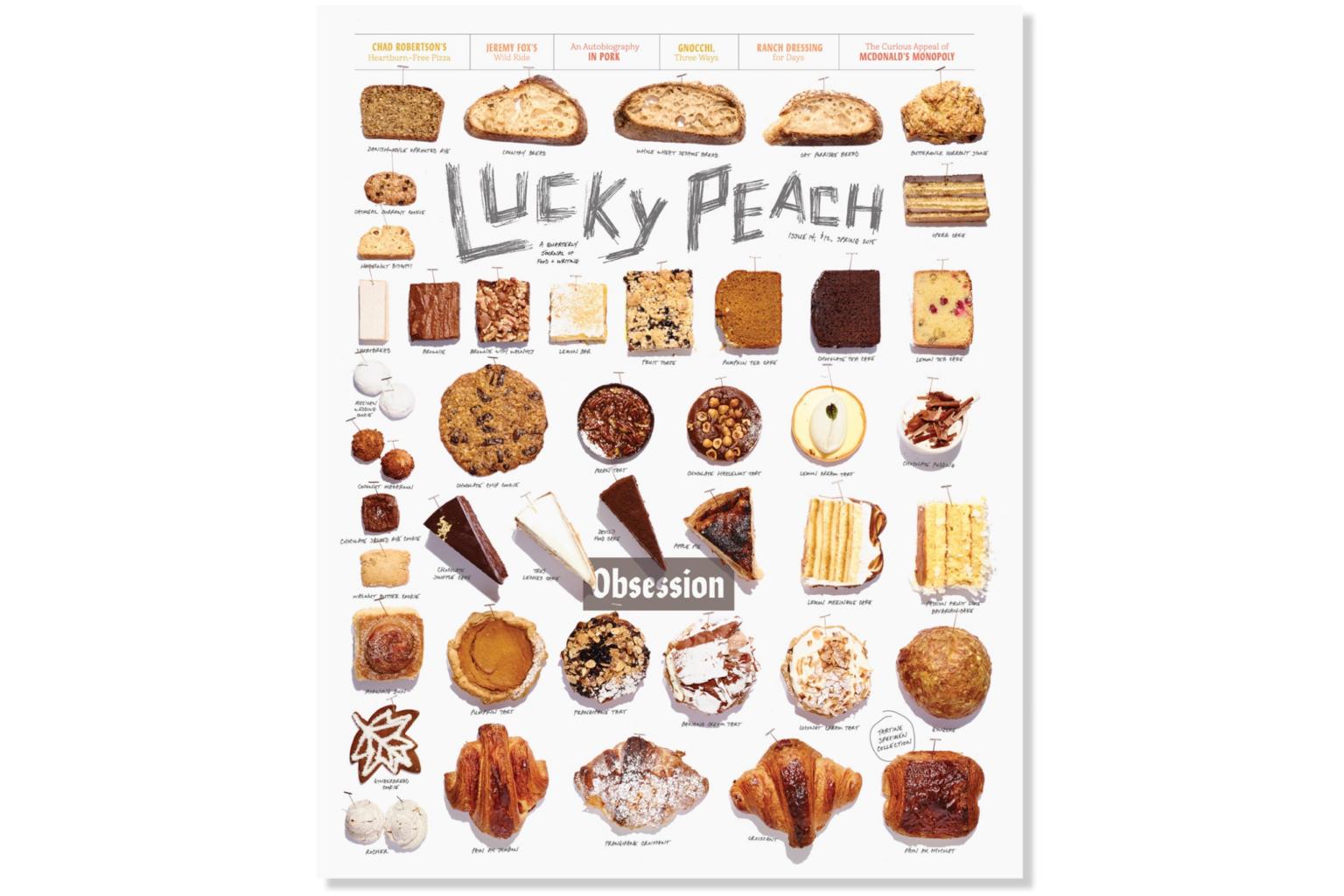

PHOTO: UNDERSCORE

Follow topic:

(NYTimes) - When it first appeared in 2011, Lucky Peach was something new: an irreverent food magazine that broke down barriers between journalists and cooks. Founded by two veteran writers, Peter Meehan and Chris Ying, and a successful chef, David Chang, it ran articles and recipes from creative minds all over the culinary landscape, and beyond.

But that alliance eventually pulled apart. On March 13, Meehan, the editorial director, told the staff of more than a dozen that there would be just two more print issues of the quarterly magazine, and that the lights at the Lucky Peach office in Chinatown in Manhattan would go out in May.

In an interview on Thursday (March 17), Meehan said that the company had arrived at a crucial moment in its growth, which amplified creative differences among its partners, as well as differences in financial strategy.

"Dave and I have had a difficult but successful partnership for years, like two objects that both have intense gravitational pull," said Meehan, who wrote the Momofuku cookbook with Chang in 2009. "It made interesting friction for a while, but I think we just kind of collided in the last six months."

All three founders have part ownership of Lucky Peach, though Chang and his company, Momofuku, hold a majority. (The magazine was published by McSweeney's until the end of 2013, and maintained a small San Francisco office until last year.)

"They're a restaurant company and we're a media company," Meehan said, "and we couldn't always find the same page."

News of the closing was reported on March 14 by the website Eater. In a subsequent letter to readers on Lucky Peach's website this week, Meehan adopted the simultaneously funny and gut-wrenching language of a father explaining to the children that Mom and Dad were splitting. "Your mom and I have been meaning to talk to you for a while," he wrote.

Lucky Peach has 30,000 print subscribers and has published 22 issues. And it has been growing, according to figures from Meehan: Print subscriptions rose 20 per cent in 2016; advertising sales in the first quarter of that year were up by 127 per cent over those a year earlier.

The staff had just started to produce branded content (articles sponsored by advertisers), the first of which will appear in a suburbs-themed issue in May. The company recently built a kitchen in its office and hired a test-kitchen director.

"The lesson here isn't that print is doomed," Meehan said.

Ying, who served as Lucky Peach's editor in chief until last year, when he took on the role of editor at large, said he had taken that step back from the magazine "partially because it had become really difficult to run a bicoastal operation, and partially because I realised that there just wasn't room for another ego in the room".

Chang declined to discuss what led to the closing. But he said he was trying to keep all options open as the magazine wound down.

"We're still talking to people who might want to help us out as a financial partner moving forward," he said. "We're trying to find an alternative, but what that is, no one really knows."

Lucky Peach plans to publish its final issue, a 200-page retrospective with a mix of previously published articles and new writing, photography and art, in the fall.

The magazine has won several journalism awards, runs a website that drew 750,000 unique monthly views in January and has produced four cookbooks.

The fourth in that series, for which the company signed a seven-figure book deal, is an egg-theme cookbook that will be published in April. The book's author, novelist Rachel Khong, joined the magazine as managing editor in its second issue and left as an executive editor in 2016.

"I don't even know how we managed to make those first issues; we were all flying a plane we had never learned to properly pilot," Khong said. "We believed in writing about food that could be distinct, irreverent, important, of literary merit. Sometimes we succeeded and other times we didn't."

In a 2011 column, the New York Times media critic David Carr, called the magazine's first issue - a ramen-theme blockbuster of 174 pages - a "glorious, improbable artifact" and "a reminder of print's true wingspan".

The magazine's contributors, who were often given space to experiment with style and voice, agreed, as did many readers who expressed their grief on social media.

"Lucky Peach was always the holy grail for me, both as a reader and a writer," said Marian Bull, who became a regular contributor. "Physically and editorially, it had a weight that necessitated print. There was an intimacy and an exhilaration that came with sitting down with a new issue."

Brian McMullen, who designed the Lucky Peach logotype, was the magazine's first art director, producing its first three issues. Collaborating with Walter Green, he helped to establish the unmistakable Lucky Peach visual aesthetic, apparent in its first issue, which was rich with art and illustration, but decidedly not in the glossy, airbrushed style of other food magazines.

Green, who stayed on for several years as art director, found his design inspiration in the archives of Spy and Mad magazine, and in the work of illustrators and artists like Daniel Clowes.

"There were definitely times when each of us had our own idea of how the magazine should be, or look," he said.

"And sometimes one person's visions won out, but it was always most exciting when those ideas all had to be reconciled," he added. "When all the different visions would have to push up against each other to create something unexpected."