Actor Miles Teller won much praise for playing the drums himself in Whiplash (2014), a movie in which he plays a drums student obsessed with being the best. He can play the drums and, for the most part, he was indeed hitting the skins.

But who the audience heard was a different matter: For the big band competition scenes, the drum sound of a professional jazz player was inserted.

Making sure that Teller's flying hands are synchronised with an external drum track takes technical wizardry of the highest order. It requires, for instance, that footage a fraction of a second in length has to be trimmed to match the picture with the sound, in a process repeated many times over the course of the movie.

It was done so seamlessly over so many scenes that it helped the movie win Academy Awards in Film Editing and Sound Mixing, in addition to the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for J.K. Simmons. In Britain, the low-budget, coming-of-age drama also won a Bafta for Best Sound.

One of the co-winners of the Oscar and Bafta, Craig Mann, tells Life! that the unique challenge of a movie such as Whiplash is the complexity.

During parts when the big band plays, other sounds need to be heard as well, such as dialogue, room noises and soloists.

Not only that, director Damien Chazelle was fond of flying the camera around the orchestra, shifting focus from one instrument to another, thus changing the sound focus. "When I read the script, what went through my mind was, 'Send help'," says Mann, 40, a Canadian who now works in Los Angeles. "It was an ambitious plan, given the time frame and the budget."

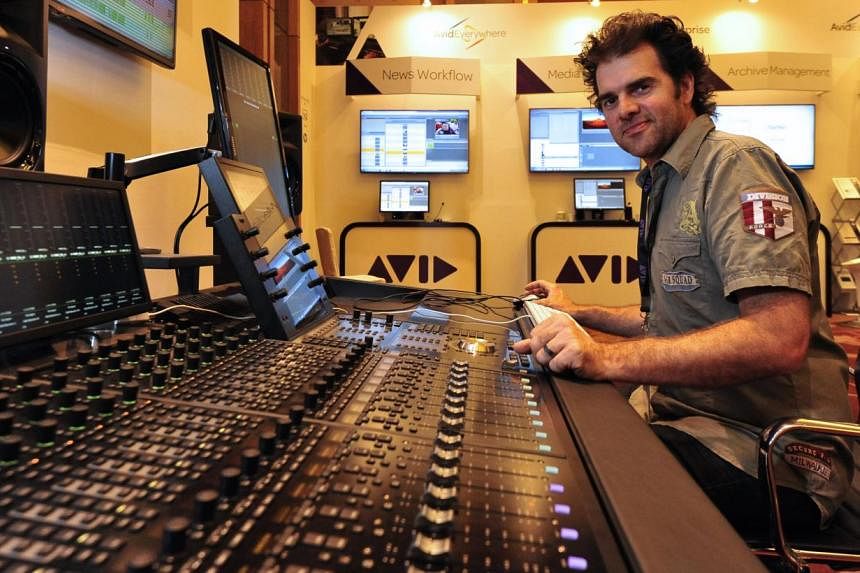

He is in Singapore to give talks and demonstrations on sound mixing as part of the BroadcastAsia 2015 trade show.

He studied music engineering in London, Ontario, before starting a career in recording and editing sound effects. He then moved to film sound after discovering an affinity for the craft.

He has worked in both sound editing, recording and mixing on everything from the thriller The Bourne UItimatum (2007), to the acclaimed war miniseries The Pacific (2010) to, more recently, the horror flick The Lazarus Effect (2015).

The 15-year veteran says his job as sound mixer is to make sure that the right sounds are heard at the right time, without harming the natural and organic feel of the overall sound. By manipulating the volume and where the sound is coming from, he says, "we tell you what to focus on and how intense we are making something by making it louder".

A typical movie will have 40 per cent of sound recorded on-set deemed unusable because of noises or other flaws, requiring sound re-recording and overdubs in a studio. Sometimes, as in the case of Whiplash, there is a need to convert the pristine, echo-free studio recording of a band sound as if the musicians had been sitting in a school's tight rehearsal space or, at other times, in a vast auditorium.

For the final scene, Mann tweaked a studio recording to sound as if the band were playing live in Carnegie Hall, by adding ambient noises to the mix.

Exhibition technology marches on as well and specialists like him have to adapt to trends such as Dolby Atmos, which places sounds in a precise spot above or around the cinegoers' heads. "More speakers means more work, but it ends up in a better presentation," he says.

The job has affected how he watches movies in a theatre, he adds. There is one spot in a cinema that audio professionals like him consider the sweet spot. "Middle centre - that's where I sit and if I can't get that, I come back for the next show."

Walking feet and shutting doors that crack like thunder, dining scenes where the chopsticks and spoons scrape and clang like cymbals, annoyingly intrusive music soundtracks... audiences sometimes cannot quite put a finger on why a television show or film feels low-budget, but often, a poor sound mix is the culprit, says Mann.

The common audience peeve about indie films is that audio effects, such as when food is being chopped in a kitchen, are too prominent in the mix.

"The team spent a long time recording that chopping, so they want you to hear it. But it's not about the food chopping, it's about the story," he says.

"A good sound mix is invisible. If you notice it, it means the sound mixer has failed."