If you watched last year's Matt Damon movie The Martian and wondered how hard living on the red planet would really be, six researchers lived in a dome in Hawaii for a year to shed light on that very question.

With the first manned mission to Mars expected as early as the 2030s, scientists know it is not just a question of getting humans there and keeping them alive, but also ensuring that they remain psychologically well-adjusted throughout - not to mention getting along with one's fellow Mars adventurers, a problem Damon's stranded astronaut did not have to face.

The experience the six researchers simulated will also be the subject of an upcoming National Geographic drama series, Mars, which airs in November and imagines the first manned mission to Mars in 2033, incorporating documentary-style interviews with real-life space experts into the story.

Speaking to The Straits Times just minutes after ending their radical experiment recently, the six crew members had this to say to would-be voyagers to Mars: They need to be highly adaptable, good with eating a lot of dried food and, above all, ready to deal with the isolation, confinement and extraordinary circumstances.

Getting along with the rest of the crew is essential to the latter, which is why the Hi-Seas (Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation) project has conducted a series of Mars simulations to figure out how best to recruit for and manage such long-duration missions.

Sponsored by American space agency Nasa and managed by the University of Hawaii, the latest project was the fourth and longest.

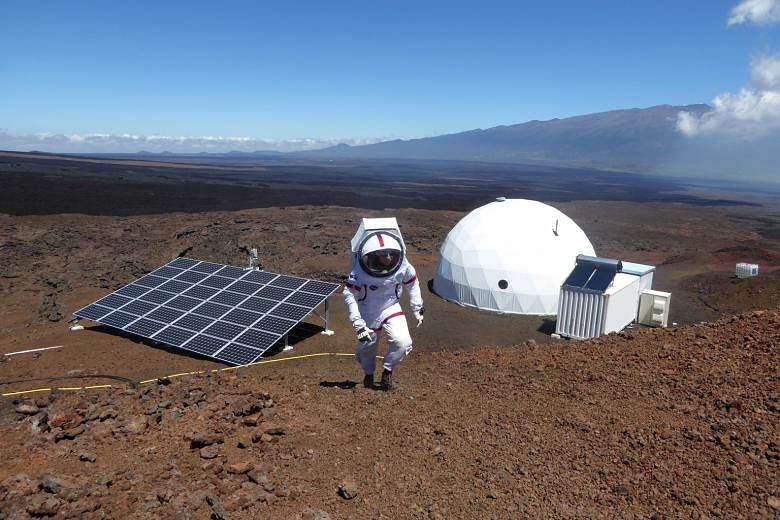

The two-storey, 111-sq-m dome clings to the north face of Mauna Loa volcano on Hawaii's Big Island about 2,500m above sea level, a spot chosen for its arid, alien-like landscape of jagged lava fields and extreme temperatures.

After 365 days of being separated from loved ones and largely cut off from the world, the sextet look dazed but elated, if a little overwhelmed, at the sea of reporters waiting for them outside.

When asked how they feel, Ms Christiane Heinicke, the mission's 30-year-old scientific officer, yells a heartfelt "Happy!" as she nurses a box of raspberries from the breakfast laid out for the crew - their first fresh meal after 12 months.

This is the first time in a year they have been out of the dome without wearing space suits, so the 10 deg C breeze on the skin feels bracing.

Biologist Cyprien Verseux, 26, says: "It's a bit weird to have people we don't know here and fresh air and fresh food and everything at once, but it feels very nice," he says.

Apart from a 20-minute delay that was built into all communications to simulate the Earth-to-Mars lag - this meant no phone calls or texting and little Internet access - practical difficulties the crew faced included the odd plumbing and medical emergency as well as the vagaries of the elements.

A plumbing snafu meant two weeks of taking showers using a bucket until the crew finally identified and fixed the problem (a filter that needed replacing).

But there was no fix for overcast days, which affected the solar panels that power the dome and led to some bone-chilling mornings in the winter.

Medical officer Sheyna Gifford, 37, had "a long list of things that I was praying 'please don't happen', because I just don't have the resources to deal with them".

She knew she could handle a few health crises, including mild to moderate cuts, dislocations and burns. But, as it turns out, she experienced the biggest injury herself, to her knee, when a lava tube collapsed beneath her outside the dome.

"I had to train a crew mate to do the evaluations on my knee because I couldn't turn myself upside down and grind my own knee into the floor to figure out how bad the injury was."

On top of their daily routines of food preparation and fieldwork outside the dome, the crew had research projects to complete.

Beyond the dome, researchers were monitoring it all as they gathered data on the six inside, with areas of study focusing on everything from social interactions to stress management.

Meanwhile, the crew were learning more about themselves and one another. The habitat has six bedrooms and feels spacious, but its design affords little privacy, reveals crew architect Tristan Bassingthwaighte, 31. "It's built for engineering efficiency, but there's no sound-proofing, so if I'm in my room with the door locked and somebody sneezes 12m away, I will hear it. So even when you're by yourself, you never really feel like you've got privacy."

Ms Carmel Johnston, 27, and the soil biologist the group elected as mission commander, admits that getting along could be tricky at times.

"One thing we all worked on was how you deal with isolation and living in confinement. And having somebody else deal with it in a different way from you can be difficult."

Asked if there were conflicts, the crew smile and nod, but are diplomatically vague about the details.

"There's always disagreements," Ms Johnston says. "Whoever's not in the argument at the time takes over the role of being the moderator."

Asked what personality traits make for a harmonious mission, she says: "I think the biggest one everybody has to have is being adaptable and knowing you can't control everything all the time. And you have to not take yourself too seriously. A sense of humour helps."

There were cultural differences too. Verseux is French and Heinicke, German, while the rest are American. "Yeah, I'm German, so I don't talk a lot," says Ms Heinicke with a smile. "And these guys are American and they talk all the time," she says, as the others laugh good-naturedly.

Jokes aside, the group has made an important contribution to the success of future Mars missions.

One of those observing them as they left the dome was aerospace engineer Robert Braun, a consultant on the upcoming National Geographic programme.

Dr Braun, a former Nasa chief technologist, was moved by the dedication of the Hi-Seas team.

"What was most amazing to me was the fact that six people would choose to spend a year of their lives, in some cases away from their spouses and loved ones, when they're not actually on Mars.

"They're doing it to advance the cause and that's pretty humbling. That's true service."

•Mars will air in Singapore in November.

Correction: An earlier version of the story stated that the upcoming Mars series is based on the experience of the researchers. This is incorrect. The fictional drama series merely shares the same subject of living on Mars. We are sorry for the error.