NEW YORK • Amy Tan really, truly did not want to write a memoir.

Her editor, Daniel Halpern, really wanted her to write one, but knew she would never agree to it.

So he urged her to write a nonfiction book about her creative process - a collection of essays, perhaps, or a compilation of e-mail messages she had written to him.

Reluctantly, she agreed. They made a pact requiring Tan to send him a minimum of 15 pages a week.

The accelerated pace unlocked something and soon, she was sending journal entries, deeply personal reflections on her traumatic childhood and harrowing family history, and candid passages about her creative struggles and self-doubt.

"I wrote this in a fugue state, not realising what I was writing," Tan, 65, said. "It wasn't until I was done that I became a little distressed and thought, wait a minute, this is going to be published?"

She realised she had unintentionally written a memoir.

The resulting book, Where The Past Begins, is not a conventional narrative autobiography. The disjointed chapters feel fragmentary and experimental, more like a collage or a scrapbook than a standard chronological excavation of the past.

Tan tossed in entries from her journals - she labels shorter ones "quirks" and longer ones "interludes" - where she muses on nature, fate, ageing and mortality.

There is an excerpt from a ponderous essay she wrote when she was 14 and a drawing of a cat she sketched at age 12. She exhumes two fictional outtakes from discarded novels, including one about a linguistics scholar that she wrote more than 20 years ago.

Tan, who has published seven novels, also reflects on her writing life and describes how she cried the day her debut novel, The Joy Luck Club, was published in 1989 - not out of happiness, but out of dread and fear of criticism.

Most books come into being through a mysterious alchemy between writer and editor. Halpern, a published poet and the publisher at Ecco, has helped to shape the careers of novelists such as Joyce Carol Oates and Richard Ford, but he has never been so visible in one of his writers' books.

In Tan's memoir, Halpern becomes a central, recurring character. She dedicates "our book" to him.

A chapter titled Letters To The Editor consists of dozens of e-mail exchanges between the two. In most of their exchanges, he plays the role of muse and cheerleader as she oscillates between earnest reflection on her work and crushing self-doubt.

In one message, after seeking his opinion on a scene, she writes: "Never mind. I deleted it. It was bad."

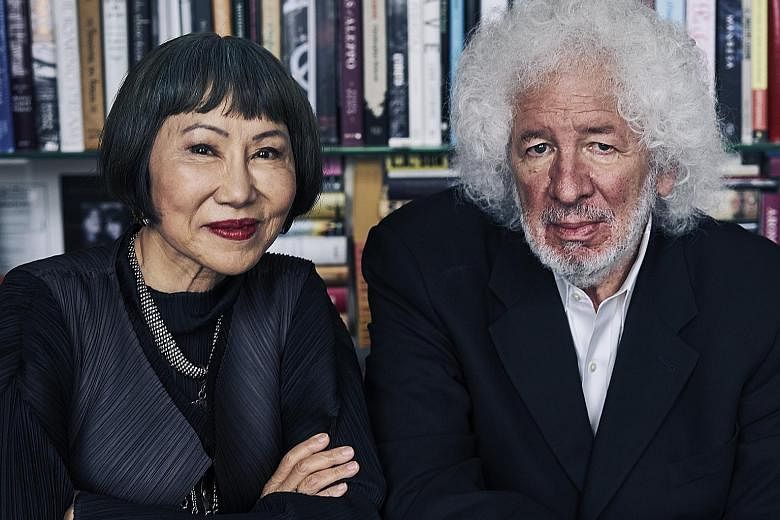

Halpern and Tan have a warm, teasing relationship, which is even more evident in person.

They got together two months ago in Manhattan, where Tan and her husband of 43 years, Louis DeMattei, a retired tax attorney, have a loft in Soho. Over a bottle of wine at a restaurant in Park Avenue South, they discussed how the memoir came together.

Halpern said: "Do you think that you will ultimately regret writing this book?"

"You know, it's not regret," Tan said. "My reluctance is always casting something out there that will be in the public and will be subject to public interpretation.

"I want nothing of that. It's like taking the mask off, taking your clothes off and having people say, 'Oh my God. It's non-fiction,' and people can make fun of the way you think or say, 'Oh that was trivial.'"

In a way, it is surprising that it took her this long to write about herself. Her fiction is full of family lore and semi-autobiographical material.

Her debut novel, The Joy Luck Club, which has sold nearly six million copies in the United States, is an inter-generational epic about Chinese mothers and daughters.

Her second novel, The Kitchen God's Wife, features a Chinese-American girl who learns about dark secrets from her mother's past and is modelled partly on her own family.

There is no shortage of dramatic material from Tan's past and she could have easily mined her childhood to write a traditional account of her life.

Born in California in 1952 to Chinese immigrants, she grew up in fear of her volatile mother. Her late mother, Daisy, was depressed and unstable. She once tried to throw herself out of the car when the family was driving on the highway.

When she was 14, Tan's family was struck by a double tragedy. Her older brother Peter developed a brain tumour and died at age 16. Then her father, an electrical engineer and a Baptist minister, was also diagnosed with a brain tumour and died not long after Peter. Her mother believed the family was cursed.

Tan also catalogues some of the trials and misfortunes she has faced as an adult: her feeling of "relief and sadness" when she had a miscarriage at 28 and her struggle with chronic Lyme disease, which she contracted in 1999.

The disease spread to her brain, causing seizures that sparked bizarre but benign hallucinations, such as a Renoir painting or a spinning odometer.

When she started taking medication to control the seizures, it made her giddy and she worried it would make her write maudlin fiction. The side effects eventually abated.

In the process of researching the memoir, she discovered more family secrets.

She found a photograph of her maternal grandmother, a concubine who died of a possibly intentional opium overdose, dressed as a courtesan. She found letters to her parents from immigration officials, warning that their student visas had expired and they were at risk of deportation.

Now that the book is about to be published, she is feeling apprehensive.

She worries about family members who might think she has sullied her grandmother's memory and is terrified of the critical response. She is accustomed to having her fiction critiqued, but this feels much scarier and more personal.

"There's so much in there that's raw," she said.

NYTIMES