A fictitious Chinese theatre company in Singapore is celebrating its 50th birthday. It is a milestone, and it decides that staging a classic Singapore work is the way to go.

But which one? A frontrunner might be the late playwright Kuo Pao Kun's The Little White Sailing Boat (1982), a landmark production that brought 14 Chinese theatre groups together. Or maybe it ought to go with the Kong Heh Musical Association's The Tune Of Life (1966), about a young woman who goes astray, staged right after Singapore gained its independence.

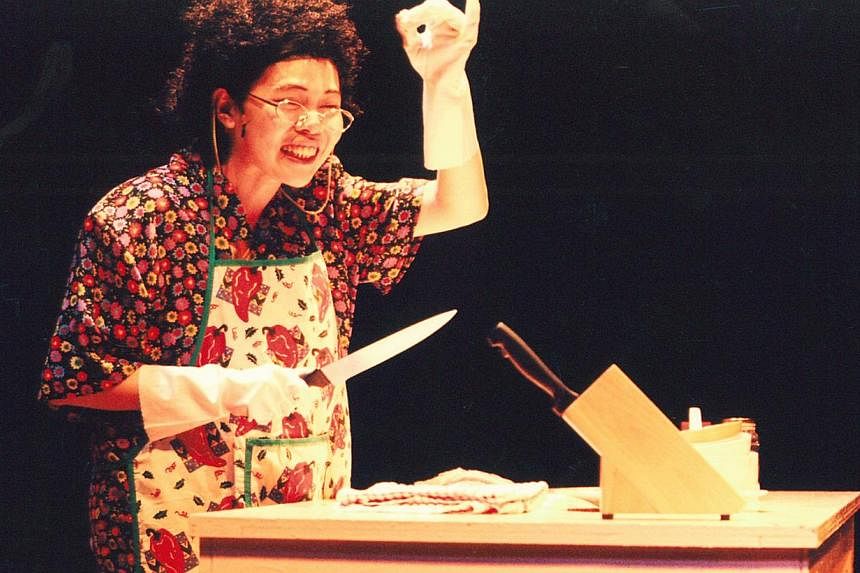

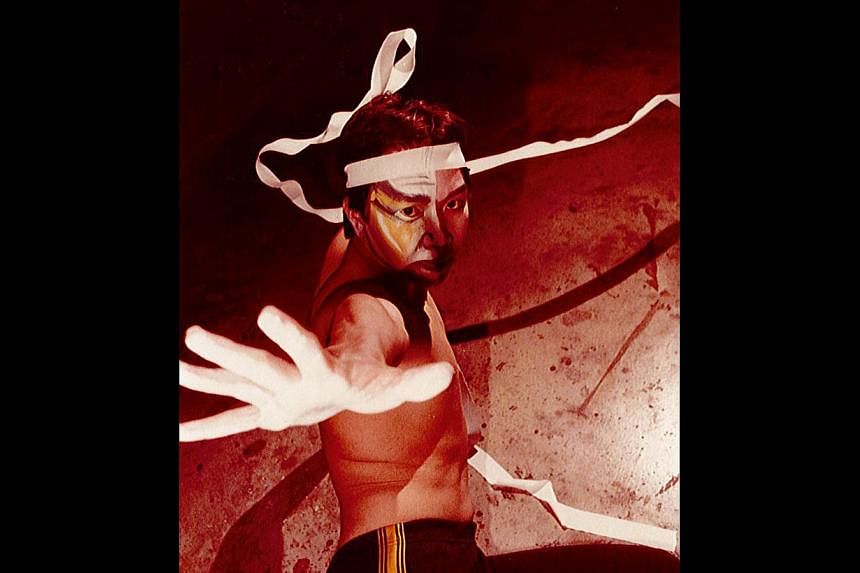

The company's artistic director goes on a deeply challenging process of selection, putting his three actors through many auditions, rehearsals and re-enactments, as they piece together the story of how local Chinese-language theatre came to be. This blend of fact and fiction includes excerpts of nine classic plays and an assortment of interviews with practitioners and other industry players.

This is the premise of Toy Factory Productions' Upstage: Contemplating 50 Years Of Singapore Mandarin Theatre, a survey of how the industry has developed over the past half a century. It runs from June 25 to 28 at the Esplanade Theatre Studio. The production is commissioned by the Esplanade and comes after the arts centre's tribute to English-language theatre from March to May, The Studios: fifty, where 50 Singapore plays unfurled over five weeks.

This time, the approach is decidedly different. Toy Factory's artistic director Goh Boon Teck takes the directorial helm of this docu-theatre production written by playwright Cheow Boon Seng in consultation with academic Quah Sy Ren, who meticulously documented local theatre in his book Scenes: A Hundred Years Of Singapore Chinese Language Theatre 1913-2013. They incorporate auditions and rehearsals into the play, alongside excerpts of plays and interviews.

Dr Quah, 51, who is script consultant, said in an e-mail interview that early Singapore theatre performed in Chinese languages and dialects such as Mandarin, Hokkien and Cantonese, were largely inspired by theatre movements in China due to linguistic and cultural connections. From the late 1950s, Chineselanguage theatre was also concerned with social, cultural and political issues here.

Upstage picks up the narrative in the 1960s and 1970s, when Chinese-language theatre was "engaged in the search of a Singaporean identity, imagining a Singaporean nationhood and demonstrating concern for the underclass", says Dr Quah.

He adds: "Chinese-language theatre should therefore not be seen as a theatre relevant only to the Chinese-speaking community and concerning issues only within that community. It is always responding to global issues and trends and should be regarded as part of and, in many historical instances, playing a leading role in Singapore theatre."

Multilingual theatre such as Kuo's pivotal Mama Looking For Her Cat (1988), for instance, had its roots in Chinese-language theatre. The Chinese- language groups here today have become increasingly multilingual. Toy Factory Productions, for example, has presented works in both English and Mandarin.

Goh, 43, notes that there has been a shift in the dominant language from Chinese to English in the theatre industry since the 1980s and 1990s. He links it to the linguistic changes in Singapore's education system, with the dominant languages moving from the various mother tongues to English. He adds: "Your brain starts to think in that language and then you watch the theatre of that language."

Many groups, often effectively bilingual, have found their niches in the scene - Drama Box is known for its socially conscious work with the community and marginalised audiences; The Finger Players' strength is in puppetry and object theatre; and Toy Factory Productions and The Theatre Practice strive for well-crafted Mandarin musicals, with the latter also organising an annual fringe alternative to the Esplanade's blockbuster Huayi festival - next month's M1 Chinese Theatre Festival, boasting a sampler platter of intimate work that is both experimental and family friendly.

For Upstage's theatrical homage, Cheow, 31, was curious as to whether theatre practitioners were aware that they were part of something greater as they were creating their work. He also wanted to "flesh out the concerns of contemporary practitioners, trying to draw some form of reference or lessons from their predecessors".

He adds: "But I think it's very important not to employ the idea or perspective that the past is always better than the present... I think that in the earlier days, there were very strong ideological differences in the sense that there are a few camps with very different planes. But as we move towards present times, there's a lot more diversity within the Chinese theatre scene."

As an example of the ideological differences of the past, left-leaning plays such as Kuo's Growing Up (1972) took the side of the workers in what was perceived to be a class struggle, while Wang Li's The Return (1967) was about how the siblings of a young arrested leftist worker try to change his views and get him to contribute to his country.

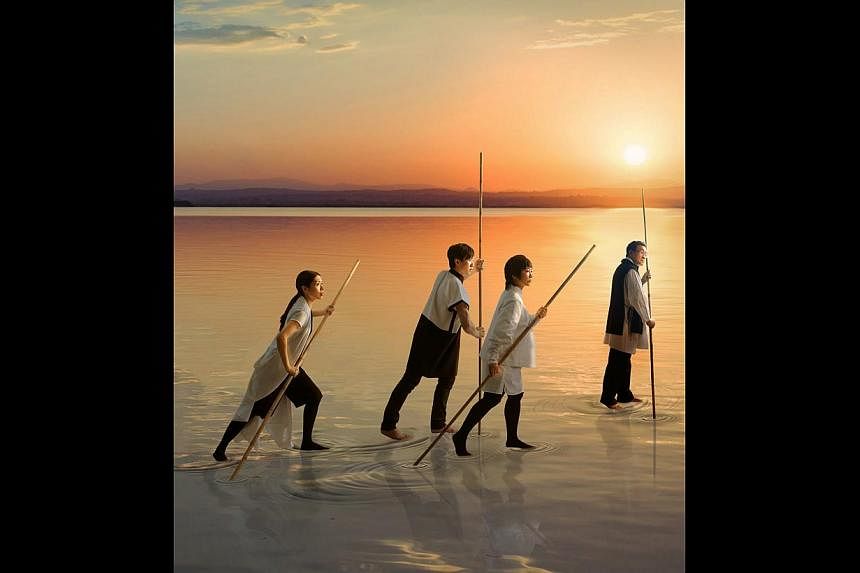

Dramatising these different concerns, Upstage will be performed by a quartet of actors: stage and radio veteran Lim Ngian Tiong, 63; seasoned director and performer Jalyn Han, 52; and up-and-coming actors Jodi Chan, 28, and Yeo Kok Siew, 34.

Yeo says their preparations for the show have been "a process of revelation": "The history of Chinese theatre is very much interlinked with the history of Singapore, both from a social and political perspective. It's really interesting to see how those affect the development and how actors or playwrights have dealt with those issues and how they are represented or manifested in these plays."

Goh says he chose performers from different generations to play off one another: "They brought in a lot of their personal preferences, memories and experiences working in Chinese theatre and we tried to incorporate those into the play too."

"Ngian Tiong is very helpful," he adds with a laugh, "because he really lived through that history. So at rehearsals, he'd say, it's like, 'In the past, it wasn't like that. They would perform it this way.'"

For instance, many of the actors were trying to speak with perfect Mandarin diction. But Lim reminded them that most performers in the past did not speak perfect Mandarin - they might have a heavy Teochew or Hokkien accent.

On being a younger performer, Chan says in Mandarin: "A lot of the time, we weren't very familiar with the material - half the time, we would be asking, 'Who is this?' And Ngian Tiong would tell us, 'Oh, this person is so and so', and he would tell us interesting anecdotes and give us some background. It was great first-hand information for us to gain a deeper understanding of the past."

Lim, a veteran radio broadcaster and voice dubber, was excited to work with younger actors. He says in Mandarin: "The arts are always moving forward. As it moves forward, it sometimes looks back. But where will the new currents take us? Those of us from the older generation are not entirely sure. Sometimes, new trends might borrow from older ones and present them in a different way.

"The younger performers are so different, whether in their rehearsal processes or attitudes - I feel it's been a very good experience for me."

Director Goh also found a great thrill in revisiting older Chinese-language work that he was not familiar with, as it was an opportunity for himself and the cast to sink their teeth into productions from the 1960s and 1970s that might have faded from modern memory.

Reading the selected scripts took several months, and playwright Cheow wanted to find "commonalities between the stories and between reality and fiction".

He chose stories and portions of stories that had overlapping themes and resonated with one another. The early plays, for instance, are often left-leaning and moralistic, reflecting the atmosphere in Singapore at the time, while later work became more experimental and collaborative as a new wave of practitioners deconstructed the work of the past.

Cheow adds of the selection process: "Like any form of historical writing, we had to focus on some and give up some, as painful as it is."

The creative team also interviewed people who worked behind the scenes and unsung heroes from the Singapore theatre scene, whose conversations will be included in the play.

They include veteran set-builder Ng Sung Soong, who built almost all of the sets for Kuo's works; logistics point person Cho Chin Hwa, who transported many sets; and Tiang Oon Kheng, who worked at the Victoria Theatre for years as an electrician and witnessed plenty of local theatre.

Lim says: "I hope the works that have been chosen as representative of local theatre will continue to be regarded by new theatre groups as points of reference and how they can continue to use them as a basis of change."

Follow Corrie Tan on Twitter @CorrieTan